Following the sequence of events outlined in Part 1, I arrived home with my unexpected camera purchase. I pulled a roll of Tri-X from the refrigerator and, while waiting for the film to reach room temperature, began to carefully examine and clean the Widelux F7. The camera appeared to be in excellent condition, though it would likely have required some serious abuse for it not to be. If today’s typical SLR is a Toyota Camry and a Leica M-series is a Porsche 911, then the Widelux is an M4 Sherman tank — it’s bulletproof in construction, utilitarian in design, and features a prominent rotating turret.

I removed the film back, sat it on the table and peered into the camera’s interior. The foam light seal that surrounds the opening was definitely showing its age. I touched it lightly with a Q-tip, which stuck to the foam like glue. When I pulled the Q-tip away, a thick strand of black sticky molasses came with it. The foam had turned to tar. I knew this would be a lengthy cleaning operation, so I ignored it for now — I was anxious to start checking the mechanical function of the camera.

I removed the film back, sat it on the table and peered into the camera’s interior. The foam light seal that surrounds the opening was definitely showing its age. I touched it lightly with a Q-tip, which stuck to the foam like glue. When I pulled the Q-tip away, a thick strand of black sticky molasses came with it. The foam had turned to tar. I knew this would be a lengthy cleaning operation, so I ignored it for now — I was anxious to start checking the mechanical function of the camera.

I raised the spring-loaded rewind knob, dropped the chilly cartridge of Tri-X into the well, and released the knob to lock the cartridge in place. Out of habit, I snatched an inch or two of Tri-X from the roll and stretched it across the back of the camera. I froze in mid-snatch — totally unsure of what to do next. This may be a 35mm film camera, but this is no ordinary 35mm film transport. In a typical camera, the film stretches across a rectangular opening, and is held flat against that opening by a pressure plate on the back of the camera. The Widelux has no rectangular opening over which to stretch the film. It has no pressure plate. Rather, the film must be threaded across a cylindrical surface, and it’s held tightly against this surface by a couple of pressure rollers. By the time I figured out that the film needed to exit the cartridge, go underneath the first pressure roller, around the cylinder, under a second pressure roller, over the sprocket gears, under/around the take-up spool and beneath a nearly invisible clip, my Tri-X had reached room temperature.

After figuring out how to load the camera, I uncovered a second problem: there is another foam light seal that presses against the second pressure roller, and it too had turned to tar. As the film advanced through the camera, it slid across the foam — picking up sticky black tar deposits on its surface. I unloaded the camera, gathered additional cleaning supplies, and quickly scraped away enough goo to allow the film to pass under the pressure roller without touching what was once intended to be a light seal.

I reloaded the film, attached the back cover and cranked the Widelux’s film transport until it stopped. The film counter pointed to a tick mark halfway between “0” and “1.” I fired the shutter, cranked the advance knob again, and this time the counter stopped at “1.” I walked out on the streets, ready and excited to start shooting some of the most contextually compelling street photos ever seen by mankind…

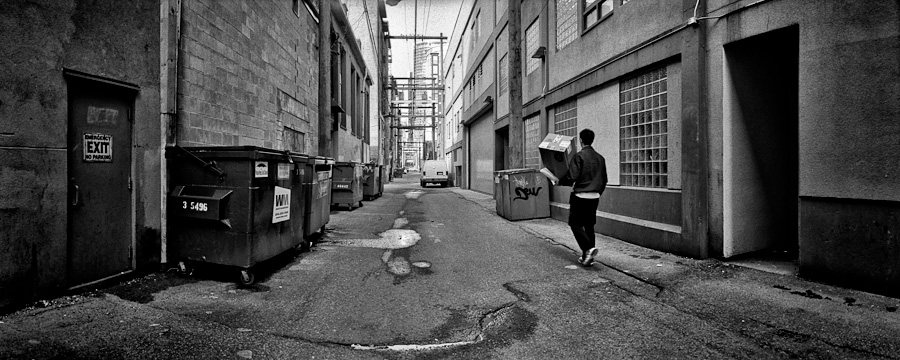

Immediately, several things became apparent: First, a 120 degree horizontal field of view is a lot of frame to fill with compelling imagery. Second, the camera offers only a paucity of exposure options. And third, a Widelux is not nearly as inconspicuous as I’d hoped. I’ll address these in reverse order.

Psychology of a Widelux

As evident in the following photo, the Widelux does not look exactly like a normal camera. Sure it’s a rectangle, and the fact that it’s wider than it is tall means it’s still less conspicuous than my Yashica-Mat TLR. But the Widelux sports a kind of industrial Art Deco look not seen on today’s Canons, Nikons, Sonys or Panasonics. It’s eye catching and, as such, catches eyes on the street. By itself, that wouldn’t make the camera overly conspicuous. But what happens is that once the camera captures the eye, it holds onto it.

Recently, I watched “The Science of Babies” on The National Geographic channel. The documentary contained a segment in which scientists theorize that infants can actually perform simple math. Since babies can’t talk or communicate, how can scientists know this? They know by watching the infant’s eyes. Specifically, when a baby sees something that doesn’t make sense, they stare at it for a long time. When something makes sense, their attention immediately shifts to something else. In this test, the baby watched a scientist place a new toy on a table. The scientist then placed a barrier directly in front of the toy to hide it from the baby. In full sight of the baby, they then placed a second toy behind the barrier. When the scientist lifted the barrier, the baby saw two toys. Makes sense, right? 1 + 1 = 2. The baby quickly gets bored and looks around at other things in the room. But then the scientist tosses in a bit of trickery — with the barrier blocking the baby’s view of the first toy, the scientist visibly adds a second toy while secretly removing the first one. When they lift the barrier, the baby sees only one toy rather than the expected two toys. 1 + 1 = 1? That doesn’t make sense, and the baby stares intently at the toy for an extended period of time. Similarly, with the barrier blocking the baby’s view of the first toy, the scientist visibly adds a second toy while secretly adding a third toy behind the barrier. The scientist lifts the board and the baby stares with rapt attention. 1 + 1 = 3? Impossible!

What does this have to do with my Widelux F7? Well, aside from confirming many people’s suspicion that photographers are a bunch of big babies, it explains what happens when I carry my Widelux down the street. Like a shiny toy, its retro-cool appearance attracts the eye of every passerby. Normally, people’s brains would simply say “camera” and their eyes would begin looking elsewhere. But when they look at a Widelux, they immediately see something “wrong” — there’s no visible lens. Right smack in the middle of the camera, where one expects to see a horizontally oriented cylinder protruding, they see a vertical cylinder. It’s like saying “1 + 1 = 3” — it doesn’t compute. And, as a result, people’s gazes remain fixed on the camera. I have seen more double-takes in the month I’ve been carrying the Widelux than I’ve seen in my previous zillion months on this planet. The Widelux is not an invisible camera. Nor is the Widelux all that quiet, since it makes a sort of “whirring” sound as the lens rotates across the field of view. But none of this should imply that the Widelux is incapable of being “stealthy.” After all, the camera captures a 120 degree horizontal field of view. This means you can point the camera in one direction, and anything or anyone standing beside you is going to be in the shot. And as I soon discovered, if I don’t observe a careful handholding technique, even my own fingers are likely to make the occasional cameo appearance in photographs.

At this point, I suspect I’m probably getting ahead of myself. If you’ve never seen or used a swing lens camera, I’ve likely just raised more questions than I’ve answered. So let’s take a step back, and study the anatomy of a Widelux.

Anatomy of a Widelux

The Widelux is about as simple as can be. Look at the top of the camera as shown in the previous photo. From left-to-right we see the film advance knob, with the shutter release immediately to its right. Right of the shutter release and toward the back of the camera is a bubble level. Centered over the Widelux logo, nearest the camera’s front, is the aperture dial. Behind it, and slightly to its right is the shutter speed dial. Right of this is the viewfinder and right of the viewfinder, on the extreme right edge of the camera, is the film rewind knob.

That’s it. No light meter. No focusing control. Nothing. Just that crazy vertically oriented cylinder that sits right smack where the lens should be.

Of course there is a lens there, and it’s a darn nice 26mm lens at that. It’s just that, when you look directly at the front of the camera, you can’t see it. That’s because the lens isn’t pointing straight ahead, but off to the side — exactly in the direction of the arrow marked on the camera’s top. The lens peeks through a little vertical slit cut into the vertical tube. When you press the shutter release, the tube, slit, and lens all rotate across the front of the camera.

Of course there is a lens there, and it’s a darn nice 26mm lens at that. It’s just that, when you look directly at the front of the camera, you can’t see it. That’s because the lens isn’t pointing straight ahead, but off to the side — exactly in the direction of the arrow marked on the camera’s top. The lens peeks through a little vertical slit cut into the vertical tube. When you press the shutter release, the tube, slit, and lens all rotate across the front of the camera.

Half of this vertical tube is visible in front of the camera, while the other half is hidden inside the camera body. It’s the hidden half of this tube that the film wraps around. As the lens and its corresponding slit rotate around the front of the camera, a much narrower internal slit rotates across the film surface, exposing it sequentially from one edge to the other.

In theory, this isn’t much different than what happens when you take multiple photos and stitch them into a panorama. In that situation, you rotate the camera around the lens’ nodal point and take numerous photos, which you then stitch together in software. With the Widelux, rather than making the photographer manually rotate the camera around the nodal point, the camera rotates the lens. And rather than exposing the scene on sequential frames, the Widelux exposes the scene sequentially from edge-to-edge within the same, extra-wide frame. The result is, with fast shutter speeds, the lens rotates so quickly across the arc that you essentially create an automatically stitched panorama of a “single moment” in time. But in reality, whatever you see on the left edge of the frame actually occurred a split second before whatever you see on the right edge of the frame. As I’ll discuss later, this can yield some interesting artifacts.

As evidenced by its lack of a focus control, the Widelux’s 26mm lens is set to a fixed focus distance. Unfortunately, the internet (being the internet) offers up several conflicting “expert” opinions on exactly what that distance might be. Ultimately, for those times I need to shoot at f/2.8, I’ll need to figure this out. But for narrower apertures, it’s a non issue — everything is in focus. The only remaining anatomical oddity I haven’t yet discussed is the bubble level. And, believe it or not, this is actually much more important than the viewfinder!

Obviously, the Widelux is not your normal camera.

Shooting with a Widelux

It may not be “normal,” but the Widelux is a very giving camera. It gives you wide negatives, it gives you curious looks from strangers and, just when you think you’ve come to grips with all its eccentricities, it gives you new ones. Case in point? How about the aperture and shutter dials? These seem innocent enough, until you actually read the numbers on them. There are only three shutter speeds, 1/15s, 1/125s, and 1/250s. It’s certainly not an inspiring array of choice, but the problem is tempered somewhat by the continuously variable aperture. But that, too, is fraught with eccentricity. Specifically, while the aperture opens to a very generous f/2.8 on the fast end, it closes to only f/11 on the slow end. Yes, you read correctly — f/11!

I’ll wait while you work through the math…

… that’s right! With a not-so-fast “fast” shutter of only 1/250s and a minimum aperture of only f/11, even ISO 100 film might sometimes overexpose on a sunny summer day. But should you venture indoors, you’ll find yourself facing the opposite problem — a not-so-slow shutter speed that will now result in underexposure.

How can anyone possibly work with a camera that has such a narrow exposure width? Three words: “neutral density filters.” For me, the best way to use this camera in a multitude of different lighting situations is to use ISO 400 film. This makes it possible to shoot indoors or in poor lighting conditions, but would obviously overexpose everything by 2-3 stops on a sunny day. That’s why Widelux cameras come with a little case full of filters — one of which is a 2-stop Neutral Density filter. Pop that on the lens, and you’re now able to shoot as if you had 100 speed film in the camera. Granted, even that might not be enough under the sunniest of conditions, but that’s where the wide exposure latitude of film rescues us again!

How can anyone possibly work with a camera that has such a narrow exposure width? Three words: “neutral density filters.” For me, the best way to use this camera in a multitude of different lighting situations is to use ISO 400 film. This makes it possible to shoot indoors or in poor lighting conditions, but would obviously overexpose everything by 2-3 stops on a sunny day. That’s why Widelux cameras come with a little case full of filters — one of which is a 2-stop Neutral Density filter. Pop that on the lens, and you’re now able to shoot as if you had 100 speed film in the camera. Granted, even that might not be enough under the sunniest of conditions, but that’s where the wide exposure latitude of film rescues us again!

I’ll wait once more while you look at the previous photo showing the camera lens hiding behind a narrow slit, then try to work out the logistics of putting a filter on it…

… that’s OK. It took me a little while too. The fact is, it’s just like that “Science of Babies” documentary all over again. Human babies are born into this world much more helpless than those of other species. The reason for this is that we have such big heads. If we were born when we were “ready,” we’d never get our giant heads through the birth cavity. As it is, a newborn’s head is already larger than the pelvic opening through which it must pass — much like a Widelux lens filter is larger than the slot in front of the lens. To be born, the baby must undergo a complex sequence of maneuvers in order twist and convolute its head through the narrow passage — again, much like a Widelux lens filter. One inserts the Widelux filter into the narrow slot by first angling it in one direction then, when it’s part way in, twisting and rotating it in the opposite direction. The filter sits flat against the front of the lens, but doesn’t attach to it. Rather, the little handle with which you insert and retrieve the filter has edges that are folded over to form a sort of “groove.” This groove then slides onto a tiny metal flange that sits near the top of the slit on the tube. It’s a wacky design and, on my camera, I found there was a bit too much “slop” on some of the handle grooves to hold the filter firmly in front of the lens. A few minutes with some needle nosed pliers solved this problem. So exposure is quirky, but thanks to the latitude of film and a pocket full of neutral density filters, it isn’t an insurmountable problem.

Since we’re already talking about mathematics and geometry, this might be a good time to mention another Widelux eccentricity — the semi-circular film surface. While most cameras have a fixed shutter that opens to expose the entire film surface at once, the swing lens has a slit that rotates across a curved film plane, exposing it sequentially. Because everything is circular — the lens motion and the film surface — the Widelux renders horizontal lines in a bowed manner. Of course, this is exactly why the Widelux doesn’t distort or stretch objects placed near the edge of the frame, which was my primary reason for choosing this camera in the first place! Because the circular motion occurs horizontally, vertical lines remain straight (unlike a fisheye, which bows everything).

On a psychological level, we as humans can easily absorb this sort of distortion and rectify it visually, like with the photo above. However, the distortion becomes much harder to digest when the camera is tilted. Once this happens, vertical lines begin to converge, and different parts of the horizon bow by different amounts — effectively freaking out the brain (like a fisheye lens). Photographers may, of course, use this sort of distortion as an effect like I’ve done in the photo below. But in ‘normal’ situations, you’ll be much happier with your resulting photos if you keep the camera as level as possible.

This explains the importance of the bubble level on top the camera. Earlier, I made the seemingly insane statement that the bubble level was even more important than the viewfinder. This is true not just because camera tilt creates such extreme distortions, but because the viewfinder on this camera is essentially useless. The viewfinder is, at best, an approximation of what the lens will photograph. I haven’t had the camera long enough to waste a roll of film on ‘scientific’ testing, but my seat-of the-pants estimate is that the viewfinder doesn’t display nearly the same height as the camera captures, nor does it display the same width. Parallax errors are extreme, and a big chunk of the right-most viewfinder view is blocked by the rotating turret. I’ve found it much easier to take photographs with this camera at chest level, rather than eye level. The arrows on the lens turret show me just how much width I’ll be capturing, and my calculator tells me that this 26mm lens will capture a 50 degree vertical angle of view, which I’ve simply learned to estimate. Basically, my rule of thumb is this: The Widelux captures everything within the absolute horizontal and vertical limits of human peripheral vision. If you can see it — even just barely — without turning or lifting your head, it’s probably going to be in frame.

Surely that’s it for the eccentricities, right? Not on your life! Earlier, I discussed how the camera exposes a frame sequentially — through a slit that moves from the left of the scene to the right. For this reason, even though you’re capturing the entire scene on a single frame with a single press of the shutter, events shown at the left of the frame happened slightly before those on the right. Thus, photographing with a Widelux introduces another dimension into photography — time.

As I write this, my Widelux is loaded with a fresh new roll of film. Because of this, I can’t run any actual timing tests, so make sure to salt everything I’m about to tell you. At the 1/250 shutter speed, it takes much less than a second for the lens to swing across the front of the camera. Maybe even less than a half a second. I don’t know, I’m not a human stopwatch — but it’s fast. Using the 1/250 shutter speed, I really don’t worry too much about motion in front of the camera. 1/250 is fast enough to freeze action, and the short time required to expose the entire frame is small enough that the left and right halves of the frame will remain in context. When the shutter is set to 1/125, it takes about a second to sweep (and thus expose) the entire frame. This can result in some interesting artifacts — particularly if an object is moving either with or against the rotation of the lens. For example, if someone took 1 second to run from left-to-right across the front of the lens, their image would fill the entire 120 degree width, making them look extremely fat! If, instead someone ran from right-to-left across the front of the camera, they would appear much skinnier than they really are. This can also result in some interesting ghosting artifacts, where you’re sometimes able to ‘see through’ people due to the nature of movement and the sequential capturing of the frame. It can also make for some very interesting horizontal light smears. At 1/15, the lens takes an eternity to swing from one side of the camera to the other. I’ve never measured the time, but it must be at least 5 seconds, maybe more. This is an avenue I have yet to fully explore, but the possibilities are massive since it really lets you mess freely with the time/space continuum.

And speaking of time and space, both also become factors when dealing with Widelux negatives — specifically, the space occupied by the negative and the time it takes to scan it. The Widelux F7 produces a negative that’s 59mm x 24mm. That’s 64% wider than a standard 35mm negative, which means you get 21 exposures on a 36 exposure roll of film. It also means the negative isn’t going to fit some negative carriers that are designed specifically for a standard 36mm x 24mm image. In my case, I have two scanners — an Epson flatbed and a Plustek 7600i Ai 35mm film scanner. The negatives are easy to scan on my flatbed, since the carriers are width-agnostic. But I don’t much care for the quality of the Epson scans. The scans from my Plustek are beautiful, but the negative carrier has vertical bars spaced every 36mm. So scanning becomes a multistep, onerous prospect. I first scan all 21 exposures with the Epson flatbed, since it’s relatively quick and painless. In Lightroom, I then make my selects and rescan those with the Plustek. Because the Plustek’s scan width is limited to 36mm, I must scan each negative in two separate passes. I insert the negative in the carrier so the left side can be scanned. I set the desired scanner exposure levels based on that side of the image, then make a scan. I pull the carrier out of the Plustek, reposition the negative so the right side is visible, then scan it using the exact same exposure settings as the first scan. I then open both halves in Photoshop and stitch them together to recreate the single image. Is it a pain? You bet! I’ve asked Plustek to send me a second negative carrier, which I’ll modify by cutting away several of the vertical spacing bars. This will save me from performing one of the previous steps — repositioning the negative between scans. But even then, scanning Widelux negatives is always going to be a bigger pain than scanning regular 35mm film.

If you’re thoroughly sick of reading about Widelux eccentricities, I have some bad news — there’s more. Most swing lens cameras (the Widelux included) are fully mechanical devices. Because they expose a frame sequentially, from edge-to-edge over a length of time, they’re prone to a unique visual defect called “banding.” Essentially, if the lens rotates with absolute precision, then every “slice” of film is exposed equally. Over time, dirt or mechanical wear can diminish the smoothness with which the lens pans the scene. When this happens, you see subtle strips of light/dark regions across your photograph. That’s because, if the lens doesn’t sweep with a constant velocity, then different sections of film receive different exposures. Fortunately, banding issues can usually be fixed by a competent repairman. Often all that’s needed is a little cleaning and lubrication, and the camera’s good as new. When I purchased my Widelux, I fully expected it to have banding issues. I was quite happy and surprised to find none.

In fact, the only mechanical problem I’ve found with this particular Widelux F7 is the disintegrating foam. I have since removed all foam remnants from the camera, which I thought would result in numerous light leaks. But I’ve seen no evidence of any leaks, and the only ill effect I’ve seen from the missing foam is that the film back rattles a bit.

When I bought the camera, I had every intention of sending it off for a comprehensive CLA (which, for you digital users, is an acronym for “clean, lubricate, and adjust.”) But here’s the thing: the shutter speed and aperture both seem accurate; there are no banding issues; and light doesn’t leak into the camera (in spite of the missing foam light seals). Frankly, I can’t see any good reason to repair a camera that works perfectly.

The only remaining quirk I have yet to fully grasp is that 120 degree horizontal field of view. As a diehard street photographer, I’m always looking for “context.” The wider the lens and the greater the depth-of-field, the more “stuff” I can include in my frame. Though challenging, this can ultimately be quite rewarding since “context” is what helps photos tell a story.

In my simple little mind, I figured “the more context, the better the story.” What I didn’t really count on was exactly how much context could be contained within such a massive field of view. A 50mm lens might be perfectly suitable for photographing a subject doing something ‘interesting.’ But if a scene is interesting because of the juxtaposition between two subjects, you’ll want to use a wider lens to capture them both (and thus the context). But the fact is, it’s insanely difficult to find scenes in which an entire 120 degree arc provides visually compelling content. For example, if someone is doing something interesting in the center of the frame, and there’s context between them and something occurring 20 meters away toward the right of the frame, it’s highly unlikely that there will also be something contextually interesting occurring over on the left edge of the frame. For anyone wanting to use the Widelux for street photography, it’s not enough to be “good” — you’re going to have to be “lucky” as well. I have yet to stumble upon a street scene that was visually interesting from edge-to-edge. 120 degrees is just ridiculously wide. Even on a trip to Portland, where I happened upon a guy playing the longest didjeridoo I’d ever seen, I still wasn’t able to fill the width of the frame with him.

I have no doubt, as I continue to employ the Widelux on the street, that there will be rare occasions when the planets align and I get a photo with a full 120 degrees of context. I suspect, when this eventually happens, that these will become some of my favorite photos. But it hasn’t happened yet, and I don’t know when it will.

Even though I haven’t yet managed to take exactly the sort of photos I expected to take, I’m seeing the potential for all sorts of new photos that I want to take — photos I would never be able to achieve with a standard 35mm camera. I’ve had it for only a month, but the Widelux F7 has already become one of my all-time favorite cameras. It forces me to completely rethink the “rules” of composition. It forces me to be extra critical of exposure and, most importantly, it inspires me to take photos that would be completely impossible with any other type of camera. If I ever get on a boat with Gilligan and he tells me I can only take two cameras, the Widelux would be one of them.

This is a camera I’ll be keeping ’til the end. So if reading this article has made you want a Widelux of your very own, then I wish you the best of luck and the happiest of shooting experiences. However, if reading this makes you want my Widelux, you’ll need to attend my post-mortem estate sale to get it.

©2011 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: All the panoramic photos in this article were taken with a Widelux F7, but with different film. Specifically, “Reflectivity vs Transparency,” “Under the St. James Bridge, Cathedral Park,” “9 Strings Per Listener” and “Didgeridooer, Portland OR” were shot on Delta 400 film exposed at ISO 400 and developed in Ilfotec DD-X. “My First Widelux Photo,” “Inside the Vancouver Public Library” and “Arcs Biennale and the Burrard Bridge” were shot on Tri-X film exposed at ISO 400 and developed in Ilfotec DD-X.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.

T hank you for writing and sharing the most comprehensive technically article are the WIDELUX camera. Your comparing it to how we see, is most valuable. I have owned one for years, and had used it professionally, and now for fun. It is a personal, private sort of camera.

Thanks, Harry: I don’t know whether to commend you for surviving an article that’s now over a decade old, or for surviving an article that’s far too long. So I’ll just commend you for surviving. To this day, the Widelux remains one of my favourite cameras, and its photos have illustrated this website many times over the years. In fact, several Widelux shots make an appearance in an article that I’m publishing tomorrow… so good timing!

I have recently acquired a F5 Widelux from a well known professional photographer when I was at the AGM of The UK Leica Society in Buxton over the week-end. It has just come back from a full service and refresh in California, so should not have any banding problems. The seller told me that if you have not used it for some time, before inserting the film, wind on a good few times and fire off to loosen up the traversing mechanism to prevent banding. In some ways the F5 has a wider range of exposure than the later cameras as it has a very low speed of 1/5th of a second capability, which would be good for interior shots with say 100 ISO film. I don’t know if this is slow enough for moving people to disappear or would it just blur them, making them look like ghosts? Fitting filters onto the front of the lens looks to be a very fiddly process, especially for my uncooperative arthritic fingers. What size are the filters, should I decide I need at the very least, an ND filter for bright sunlight.

Wilson

Hi Wilson. The Widelux requires its own special set of filters, which have a unique attachment mechanism and a little “handle” for mounting/removing. Standard filters will not work.