A couple years ago, I was out shooting on the streets with a late–1940’s model Leica III. As often happens, a stranger approached me, pointed at my camera and struck up a conversation. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the dialogue follows a predictable path: I’m asked if film is still being made; why I’m shooting it; and where one goes to get it developed. But this was not one of those ninety-nine times.

Instead of initiating the expected discussion about the availability and merits of film, the gentleman’s first question was “can you still find batteries for that thing?”

I replied that the camera didn’t require batteries, to which he responded, “then how can it possibly work?”

I told him it was all mechanical.

In a condescending manner, thinly disguised as stoic mentoring, the man informed me that I must not know very much about cameras, because some sort of power source would obviously be needed to operate the shutter.

“A spring and some timing gears,” I responded.

The man tightened his lips into a scornful smirk, shook his head in pity at my manifest ignorance, and walked away.

What made this encounter all the more curious is that my would-be tutor wasn’t all that young — mid–30’s, I’d guess. Generationally speaking, he was certainly old enough to have had either first- or second-hand experience with film cameras. But then, he didn’t ask me about film — he asked about batteries. I tend to think that only digital cameras are products of the consumer electronics industry, but in reality cameras became electronic devices long before the pixel pushed aside the silver halide crystal. Batteries have been juicing camera bodies since auto-focusing replaced the split image; since built-in metering and exposure-priority modes supplanted the Sunny–16 rule; and since automatic film advance superseded a precisely crafted assortment of ratcheted levers.

So, attitude aside, I can’t really fault the poor fellow for failing to know the finer points of camera history. He’s the one living in the here and now, while I’m the one carrying a mid–20th century mechanical film camera in the 21st century.

The Givethness and Takethness of Technology

Photography is and always has been a technologically driven medium. In order to stand out from the pack, photographers must create something different than what their peers create. Technology — with its promise of freshly contemporary images and a more effortless way to achieve them — provides the path of least resistance. The irony, of course, is that the majority of photographers attempt to differentiate themselves by pursuing the same technological advances, thus ending up right back where they started — creating work that’s indistinguishable from the pack. And so technology cranks the wheel again… and again… and again.

Similarly plagued, but with an entirely different illness, are those photographers with creative aspirations that come from within, rather than as a byproduct of modern technology. I’m one of those guys — in fact, each major advance in camera technology seems to widen the gap between how a camera operates and how I actually need it to operate. To a photographer on the technological treadmill, this might sound like nirvana: no more straddling the bleeding edge; no more learning and re-learning and re-re-learning the latest techniques; no more fistfuls of money thrown at the next big trend, only to see it fade into the inevitable cliché.

But such nirvana is merely an illusion, because gear is always going to be part and parcel of the image making process. So, while it’s true that photographers such as myself aren’t slaves to modern gear cycles, we are slaves to particular types of gear — specifically, we’re slaves to the types of gear best-suited to the work we’re trying to produce. And more often than not, because the photos we hope to create aren’t trendy, the gear we need is no longer being manufactured.

Which all helps explain why my 21st century condo has a cabinet stocked mostly with mid–20th century mechanical film cameras. It’s because no other class of camera has ever satisfied my photographic tendencies, aesthetics and desires nearly as perfectly as the 35mm mechanical rangefinder.

The Leica Lineage

My favorite camera is my 1958 Leica M2. Ergonomically, it’s nearly perfect and is a model of utter simplicity. There are no modes. No menus. Nothing to set, configure or interpret. It’s simply a light-tight box that fits comfortably in hand, holds the film flat, and allows me to mount some of the best (and smallest) optics ever created. Of all the cameras I’ve ever used, it provides the lowest barrier between seeing a photographic opportunity and photographing that opportunity — a rather important consideration given my preferred subject matter: the fleeting and the ephemeral. It’s also built like the proverbial tank — something that’s becoming increasingly more important now that the camera is entering its 57th year on this earth.

The camera for which I’ve long-lusted, but have yet to own, is the Leica M4. It was released in 1967, and replaced both the M3 and M2. Leica retired the M4 in 1972, but brought it back briefly in 1975 to help restore some financial stability after the M5 debacle. So what is it that makes me yearn for an M4 when I already own a perfectly good M2? Simple: it’s younger. When your photographic leanings are as anachronistic as mine, you start to worry a bit about the age of your gear. Although the M4 does offer a handful of improvements over the M2, most have no direct effect on its ability to “get the shot.” The sole exception would be the self-resetting film counter, which the M2 lacked. Technically, if I were smart enough to remember to manually set the M2’s film counter to “1” each time I loaded a roll of film, then I wouldn’t need a self-resetting film counter. But since I’m not that smart, I often find myself in the middle of a shooting opportunity without any clue of how many shots remain.

So if my M4 desires are primarily age-driven, why not lust all the more vigorously for an M5, M6, M7 or MP? Why not the M4–2 or the M4-P? After all, these are all 35mm rangefinder film cameras, and they’re all newer than the original M4 (save for some M5’s, of course).

The answer is subtle, but equally simple: I haven’t salivated over these other cameras because I consider them to be cousins, rather than direct descendants of the M3>M2>M4 bloodline. These cameras are all products of the industry’s inevitable technological evolution — each subsequent model adding electronic features I neither need nor want, while simultaneously cheapening internal components and compromising build quality. Don’t get me wrong — they’re still mighty fine cameras. In fact, I actually own an M6TTL, and while it succumbs to the inclusion of a built-in light meter, its exposure setting remains 100% manual and its shutter 100% mechanical. I had Leica replace its most egregiously cheapened component (the rangefinder itself) with the improved, flare-resistant version from the later-model MP. So with the battery compartment left empty and a bit of major surgery, I’m able to coerce some “old school” usefulness out of a camera that’s quite a bit younger. But it’s still a product of the 20th century, and it’s still not as pure of purpose as the original M3>M2>M4 line.

I assumed this would forever be my fate: seek out old Leica mechanical film cameras, buy them, and ship them off to qualified camera technicians until the last living craftsman sheds his mortal coil, leaving behind no earthly soul to clean, lubricate, calibrate, repair or modify them. It’s not like I have other options — my tools of choice are the tools of an earlier generation. The world keeps spinning, technology keeps evolving, and time ticks forward — day by day, week by week, year by year. Nothing can change this…

… or can it? Einstein theorized that time is not an absolute quantity but is instead a malleable variable within the larger concept of spacetime. But this is only a mathematical theory, not a law. No one’s physically proven it…

… or have they?

In late 2014, Leica released a new camera — a film camera. A fully mechanical, fully manual, meterless, batteryless slab of solid metal and brass, the Leica M-A. It is, without a doubt, the true and rightful heir to the M throne — the direct descendent of a royal bloodline that began with the Leica II in 1932, and ended in 1975 with the discontinuation of the Leica M4. What followed was an ascension of contenders and pretenders — each excellent in its own way but, as I stated previously, each only tangentially related to the original bloodline. But the M-A is a direct descendent — the camera that should have inherited the M4’s throne back in 1975, but didn’t…

So how is it possible that, in 2014, Leica has managed to release the true and logical replacement for the M4 when it’s already released a dozen different M model cameras in the interim?

Simple: Leica has folded time.

Their stunning achievement left me with an odd combination of feelings: gratitude; disbelief; depression. Gratitude because I now know there’s a brand new camera on the market that’s actually an ideal fit for my photographic proclivities. Disbelief because, let’s face it — did anyone actually think a major camera company would release a professionally spec’d, fully mechanical, fully manual film camera in 2014? Depression because, like everything Leica makes, the M-A is priced significantly out of my comfort zone.

The Leica M-A: Four Steps Forward, One Step Back, a Huge Leap Sideways, and the Road to Perfection

Considering my assertion that the M-A is the successor to the M4, it makes the most sense to “review” the camera within that context. What has Leica improved? What have they messed up? What hasn’t changed? What needs to change?

Let’s start with a list of tangible improvements over the M4:

• The addition of 28mm and 75mm framelines

While the previous-model M4 offered only 35, 50, 90 and 135mm framelines, the M-A foreshadows the “future” model M6 through these two additions — proof that Leica has been folding time for quite awhile now.

Although my use of the 75mm focal length is spotty at best, 28mm is my “go to” focal length — so it’s quite useful to have these framelines included with the camera and not have to guess framing (or use an external viewfinder).

• The return of the 1-piece film advance lever

I know this will sound ridiculous, but I always thought the film advance lever on the M3 and M2 was a mechanical marvel — not because of its complexity, mind you, but because of its simplicity — a single, perfectly balanced, perfectly shaped, perfectly ergonomic lever that practically begged you to flick it and ready yourself for another shot.

Leica introduced a redesigned 2-piece hinged lever with the M4 — a design they carried forward though the M5, M6 and M7 lines, before finally reverting to the 1-piece lever with the MP. I never really cared for the 2-piece lever. It was slightly less ergonomic and slightly slower to operate — seemingly insignificant should one be photographing static subjects, but rather important should one need to fire off a quick succession of shots with split-second accuracy. Needless to say, I’m quite happy that the M4’s successor has reimplemented the 1-piece film advance lever.

• It comes in black

This is another one of those subtleties (like the film advance lever) that might not seem all that important to many, but is very important to me. Although I think chrome cameras are far more beautiful and definitely look nicer sitting on a shelf, black cameras draw far less attention in public — and since I’m the sort of photographer that works in public and tries to draw the least amount of attention to himself as possible, flat-black cameras are an essential part of my process.

Yes, Leica did make a smattering of black M3, M2 and M4 cameras back in the day, but the vast majority were chrome. The rarity of the black variant makes them particularly attractive to collectors, and thus exorbitantly expensive. This means, prior to the introduction of the M-A, I was stuck either using a chrome body or paying to have it painted (which is exactly what I did with my Leica IIIc). By offering customers the choice of ordering their M-A in “display quality” chrome or “street quality” black, Leica has improved the bloodline that much further.

• Removal of the residual flash bulb synchronization contact

This improvement is quite minor indeed — even for me! But with flashbulbs no longer really needed or available, it makes little sense to include a bulb-sync terminal on the M-A. One less hole in the camera; one less snap-on cover to lose; one less thing to poke you in the eye.

I would suggest that the Leica M-A’s one and only backward step is the return of the rewind knob. Prior to the M4, and dating all the way back to the Leica II/III days, Leica cameras employed knurled knobs to rewind the film. With the M4, Leica replaced that torturously slow finger-grater with an angled, folding rewind crank. This made changing film much quicker and significantly less painful. Besides, I quite liked the way it jauntily angled into the top plate — giving the tried-and-true M-shape a bit of understated flair. I have no idea why Leica decided to return to the flat, knurled knob design of the older model cameras. Perhaps its less expensive? More durable? I’m not sure. Fortunately, I use my Leica IIIc, IIIf and M2 frequently enough that I already have a protective layer of calluses on my thumb and forefinger.

Of course, as close as this bloodline comes to being the “perfect” tool for my needs, it’s only natural that I’d like to see at least a couple of improvements to the M-A’s successor (should Leica see fit to fold time once again). Specifically:

• A shutter lock

My shooting technique requires use of a soft-release button, which threads into the camera’s shutter release socket. Using a soft-release further decreases the amount of time between deciding to take a photo and actually taking it. Sure, it’s a time measured in milliseconds — but for my work, milliseconds matter. Also, because I don’t release the shutter with my fingertip, but with the Distal Interphalangeal Joint (thank you, Google), I’m able to hold the camera steady at much slower shutter speeds.

Not surprisingly, the soft-release’s main problem is the same as its main benefit: tripping the shutter is ridiculously easy, which means accidentally tripping the shutter is also ridiculously easy. Camera bags are the natural enemy of the soft-release button. Statistics show that 73% of the time you place a cocked camera in a bag, you will accidentally take a photo of the inside of that bag.

The most obvious solution would be to simply not advance the film (and thus not cock the shutter) immediately after taking a photo. But that’s a learned behaviour that’s long-ingrained into my photographic process. To unlearn such behaviour would take the rest of my life. And even if I were to unlearn it, I’d have a subsequent problem: every time I’d try to take a shot, I’d forget that I hadn’t previously transported the film or cocked the shutter. So this is simply not a workable solution for me.

The second-most obvious solution is to simply not put the camera in a bag. And while this is, indeed, a solution that I sometimes employ, I should mention that I live in Vancouver BC, which is located smack in the middle of the largest temperate rainforest on earth. Bags are sometimes rather necessary to transport cameras from point A to point B.

The third-most obvious solution is to simply unthread the soft-release button every time I put the camera in a bag. This, too, is a solution I sometimes employ, but it’s fraught with its own set of problems: namely, the combination of tiny soft-release buttons and big clumsy fingers (particularly when in the presence of sewer grates) causes the premature demise of said buttons.

So this is why I want every Leica camera to have a shutter lock. Lock the shutter, and I have no photos of the inside of my camera bag; I have no wet camera; and I’m no longer donating soft-release buttons to the Vancouver Public Works department.

• On-camera diopter adjustment

OK, I know. I’ve gone on and on about how old camera technology is better-suited to my particular style than new technology, but there comes a point when you gotta say “enough is enough.” Since the dawn of time, the only way to adjust the diopter setting for a Leica rangefinder has been to purchase an overpriced, screw-on diopter attachment of fixed value. I’m sure this is a nice little revenue stream for Leica, but come on — throw us blind guys a bone here.

Heading up the “doesn’t really matter” category of M-A features is Leica’s decision to retain the Rapid Load mechanism, which first appeared on the M4, and which replaced the old 2-spool method employed by the M2 and its parents. Though I would never have expected Leica to return to the oft-disliked 2-spool loading method, I must admit that I prefer it to the Rapid Load, which I find to be a bit more finicky. I suspect I’m in the minority here, and since the Rapid Load doesn’t affect the camera’s picture taking prowess, I’m perfectly fine with Leica’s decision to satisfy the majority of its customers rather than a few of its more peculiar ones.

Also in the “doesn’t really matter” category (at least for me) is the fact that the M-A’s shutter speed dial returns to the smaller, clockwise-increases-speed orientation of the original lineage. Leica increased the diameter of this dial substantially when the M5 was released — an ergonomic decision that makes it much quicker to change shutter speeds than with the smaller dial used by the M3, M2 and M4. Leica again changed the dial size when they released the M6 — making it smaller than the one on the M5, but still larger and more ergonomic than those on the earlier M’s. Beginning with the M6TTL, Leica inexplicably reversed the direction of the dial, such that a counter-clockwise rotation would set faster speeds. They continued with this larger, reverse-rotating dial with the M7, and on into the digital M8, M9 and current M (240) models. At this point, I own two cameras that use the large, counter-clockwise dial (M6TTL and M9) and three cameras that use the small, clockwise dial (M2, IIIc and IIIf), so it really didn’t matter which methodology the M-A employed. All that mattered was that if the dial were indeed small, then it would rotate the same direction as the old cameras. And if the knob were large, then it would rotate in the direction of the newer cameras. I’ve trained my muscle memory to recognize dial size as the indicator of which way to turn it. I have no idea what original-model M6 owners do, since those cameras have large dials that turn in the direction of small-dial cameras. I suspect Leica went back to the original small, clockwise-to-quicken dial because this would make the new M-A compatible with all the old shoe-mounted exposure meters that some folks like to mount on top.

Everything else about the M-A is exactly what I would have hoped: The one-piece, full-metal body with solid brass top deck and baseplate insures this camera will truly last for the rest of my life. The rangefinder is clear, bright and precise as only a newborn Leica’s can be. And that classic, rubberized-cloth focal plain shutter, which remains mechanically controlled and exquisitely quiet, continues to protect my delicate proboscis from the potential ire of many a subject.

Conclusions

In the world of on-line camera reviews, I’m aware this one stands out as somewhat unique — but so is the Leica M-A.

I barely discussed camera features because, frankly, the camera’s total lack of features is its primary feature.

I discussed nothing about the camera’s image quality because that’s more a product of the lens used, the film chosen, and the developing technique applied. In fact, prior to writing this article, I considered including only photos taken of the M-A, and not by the M-A. The conceit of this plan was to illustrate that the camera’s only function is to transport the film, hold it flat, open the shutter precisely when commanded and keep it open for an accurate duration of time. What purpose would be fulfilled by showing photos? Particularly the type of photos that I favor? It’s not like I’m going to start taking some pedantic photos of clock towers or some hackneyed reflection shots, just because I’m writing a camera review.

But, ultimately, I decided to go ahead and include some photos — mostly because readers will expect them, but also to help break up the significantly long blocks of text contained within this article.

And speaking of significantly long blocks of text, I’m fully aware that this is a very long article for what’s ultimately a rather short review — but that’s because the true beauty of the M-A is not revealed within its specifications, but within its lineage and its gestalt — important factors in understanding what it is that makes such a simple camera so wonderful.

At this point, I suspect several of you are wondering whether or not I won the lottery. After all, how else could a mere photographer — particularly one whose stylistic choices are as unpopular as mine — afford to buy a new Leica M-A?

And the answer, sadly, is “I didn’t.” I asked Leica for a review sample and, surprisingly, they complied. Regrettably, I possessed the camera for only two weeks, and those two weeks happened to coincide with the Holidays, a photo-precluding excursion to Portland, copious quantities of Vancouver rain, and a rather significant and extended migraine. But in spite of all the deterrents, I still managed to run 5 rolls of Tri-X through the camera — more than enough to draw the conclusions outlined in the article, though obviously not enough to have assembled a compelling collection of photos. Still, it’s all I needed to realize that this camera must somehow, someday be mine.

Though few photographers will care or understand, Leica has done something truly extraordinary — they’ve revitalized a camera bloodline that was essentially left for dead 40 years ago. And by doing so, they’re helping to extend the life of a particular style of photography — a style that’s heavily dependent on 35mm rangefinder film cameras — for several generations to come.

There’s a faint but tactile unease emanating from within the big cabinet o’ cameras that sits inside my tiny little condo. Cameras may well be inanimate objects, but they know. They know I’m eyeing them, prioritizing them, and placing dollar values on their pretty little vulcanite hides. There’s enough of ‘em in there to finance a new Leica M-A… I know it. And so do they…

©2015 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS:With the exception of the two photographs depicting the M-A itself, all the photos in this article were (of course) shot with the Leica M-A. Needless to say, that fact is rather meaningless. What’s perhaps of more interest is the lens, film and developer used to create each photo. To keep things simple, I shot everything on Tri-X exposed at ISO 400, and developed it in HC-110 (Dilution H). The sole exception was Mobile Office, which I shot on some decade-old expired Tri-X at ISO 320 — an experiment I did not continue since some minor fogging was evident on the negatives. That leaves us with only the lenses to discuss:

- Mobile Office was shot with a Voigtlander 50mm f/1.5 Nokton-M

- Hear No Evil utilized a Leica 28mm f/2.0 Summicron-M

- Crosswalk found its way here via a Voigtlander 21mm f/4 Color-Skopar

- Death Takes A Dip employs a Leica 28mm f/2.0 Summicron-M

- False Creek, Vancouver BC used a Leica 50mm f/2.0 Summicron-M (v5)

- Aptly Named required my trusty Leica 28mm f/2.0 Summicron-M

- Rocket Man was shot with a Leica 50mm f/2.0 Summicron-M (v5)

- The Clock Atop Vancouver Block was photographed with my woefully underutilized Leica 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit-M

- Underworld comes compliments of the Leica 35mm f/2.0 Summicron-M (v4)

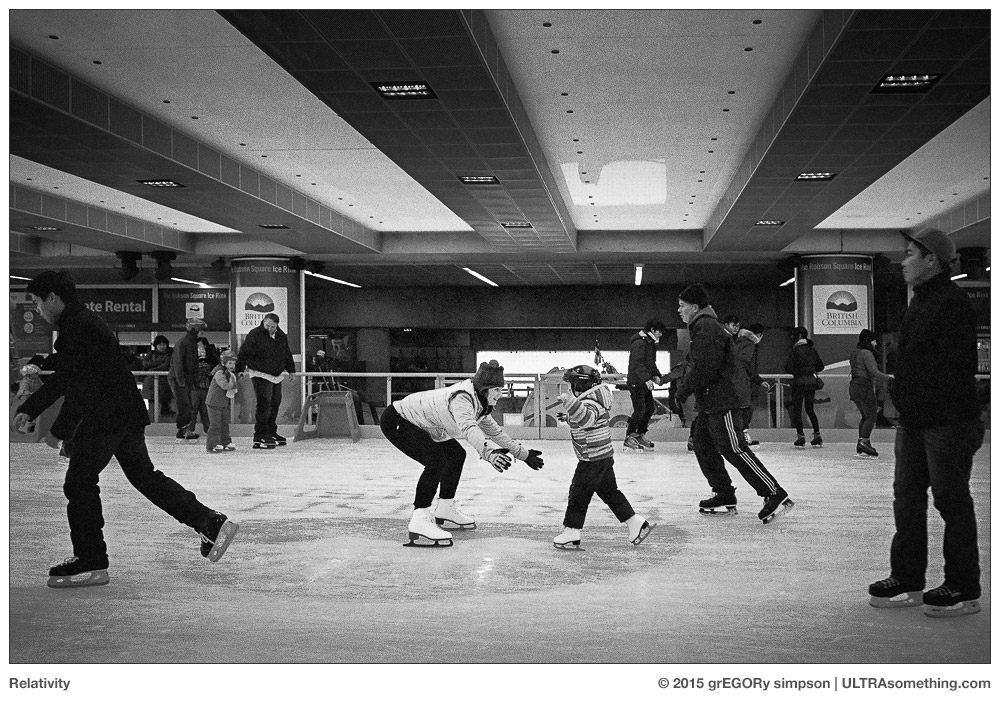

- Relativity is a product of the Leica 28mm f/2.0 Summicron-M

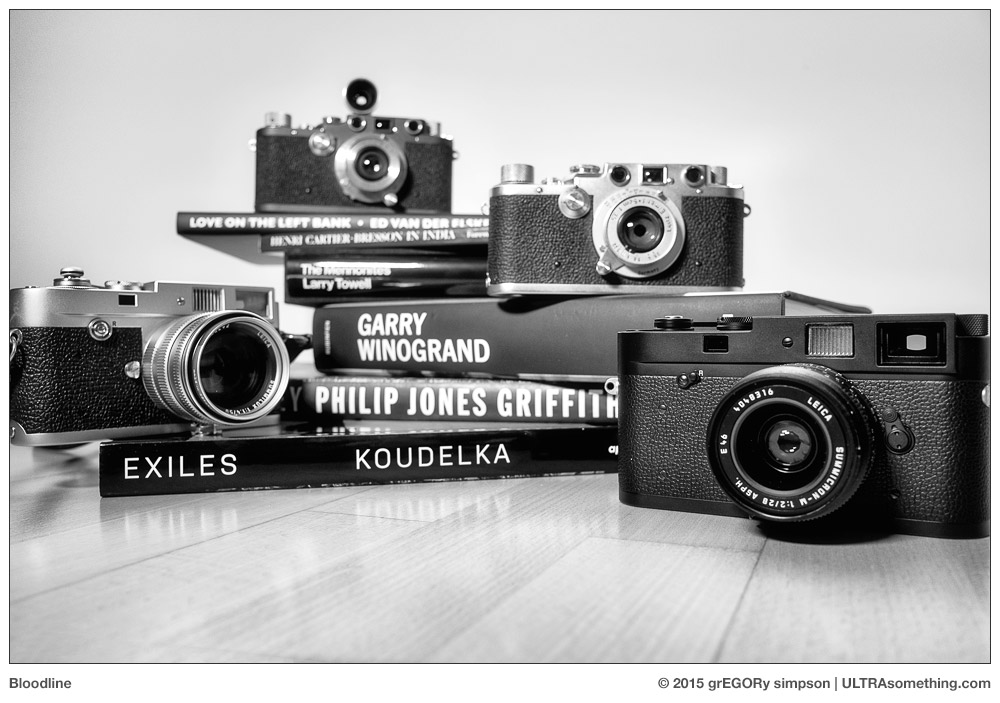

Incidentally, because I’m likely to be asked about it, I should probably identify all the participants in the Bloodline photo shoot. In front and in-focus is the Leica M-A, sporting the tried and true 28mm f/2 Summicron lens. Slightly behind it and on the far left is the Leica M2, wearing the ultra-rare 1999 special-edition thread-mount 50mm pre-ASPH f/1.4 Summilux, which was made exclusively for the Japanese market (and, yes, I am willing to sell it). Further back and sitting atop the Winnogrand book is the Leica IIIf, sporting a classic 50mm f/3.5 collapsible Elmar lens. And in the very back, barely in focus, is the stunning Leica IIIc, resplendent in its gun metal grey paint, 35mm f/3.5 Elmar lens and matching Voigtlander 35mm viewfinder.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.

Hi Gregory,

Appreciate Very Much the contents of the well written in-depth article on the Leica MA and relevant comparisons with the other Models

I have been content owning and using the only just an M3 and F/5 cm 1.5 Summarit lens and a Collapsible F/ 2.8 Elmar lens and a old functioning with selenium cells and booster-Metrophot Light meter for about a year since I acquired it.

I also use sometimes the various metering charts and the sunny -16 rule to shoot besides the pocket light meter on the iPhone 4s and also by the eye.

If Opportunity opens the gates again would love to acquire a much later and a fresh or newer model and lens to continue my analogic experience of going about capturing images in the old fashioned way.

i am located in Brazil and these models are only seen on the web at exorbitant prices and far beyond the comfort zone to acquire at present .

Even the b/w films are more exorbitant here in Brazil,

Although, I did manage to acquire 3 Rolls of Tri x from eBay USA once last year and some Ilford FP 4 – Currently not available locally and loved it .

Now currently looking forward to acquire fresh B/W ( Kodak Tmax 100 / Tri X 100

or Ilford FP 4 films to shoot.

Well, I liked the Pics you shot with the MA

Hi Gregory

Thank you for this well thought out and well written review. I’ve had to go through it a couple of times now and I’m sure I’ll come back to it again in the near future. I’ve never shot with a leica before but it’s always cool to live vicariously through passionate users like yourself. Im glad I found your site through googling for the leica m-a and seeing all your other topics here, makes for good readin’. Anyway just rambling here, good job and keep up the great work! I’m looking forward to your next article.

I have a different perspective on the MA.

I had all M except the M5.

sorry to be a bit pedantic

The MA is not an MP without a lightmeter….

The MA is i an incident meter camera,the MP is a reflect meter camera.

what you do to evaluate this incidence light is an other question (f16 / handle lightmeter/ Telephone app).

everybody who know a bit about photography will understand that controling the light is key.

if you go on the slow side of doing photography ( oposite to point and shoot) than you will one day meet this incidence light and found it peacefull and very acurate for black and white photography.

the growing of mesure methods in the mid xx century was due to the appearance of kodak color and slide films who are narow in their way accepting different lights.

not the cas sith trix were you can mesure a scene and do everything with one mesure….and sometime some bracketting.

last but not least….when you use the mp/m6 it is very difficult not to be driven by theses bright red triangle….and be slave of it …even worth with your aperture ring wich is more easier to move tham the speed ( except the ttl )

and when it is good you press…

with an ma you are free to compose.

the mesure is done far before.

So the ma and the mp are two brother, eith teo different philosophy.

hello francois,

thank you for your analysis and philosophy regarding the Leicas.

I have an M6 and an MP. When I travel I load one with color and one with b/w which is why I have two. I use the 28-50-85 set up for lenses.

I must say I think you are spot-on with the philosophy.

Not long ago, I was visiting my granddaughter who was about a year old at the time so I grabbed my MP and 50 lens and then realized i had removed the batteries as I wasn’t planning to shoot for awhile. So I said the heck with it and grabbed my hand meter. When I did the shoot (outdoors) I took the incident reading on her face and my daughter’s face (who was holding her child) and shot the roll. What a feeling of freedom, just advance the film compose – focus – shoot.

I have wanted an MA for awhile and I think I will eventually give in.

Thanks so much,

Hank

Just plunked down my spare change for a new black M-A. I have had every Digital camera out there, even the Df and a couple of digital Leica’s, none have given me the satisfaction of a meterless rangefinder. But alas they were stolen three years ago. So now it will be me and my new M-A and oh…. my iPhone 12 pro.

Just read this review. I enjoyed it very much. I bought a used M3 back in the 80’s. Like a fool I sold it 20 years later to go digital. Digital and I rotated thru many cameras but I was never really happy. I bought a black M-A last year. I am 71 years old so this my “forever” rig.

Hi Kivis: It’s always nice when someone checks in on one of my ancient articles, and takes the time to comment. Thanks. And congratulations on the M-A. Although I’m not lucky enough to own an M-A, I do own several far older Leicas — all of which will be ‘forever’ cameras… though, old as they are, they might require at least one more CLA trip to tide them over — assuming there will be anyone who will still posses the skills to do that in the future…