In February 2013, on one of my then-frequent trips to Portland Oregon, I made one of my then-frequent visits to Pro Photo Supply to feed my then-frequent habit of shopping for interesting old lenses. There, sitting amongst a collection of gleaming chrome products in the impeccably tidy glass Leica display case, sat some sort of gnarly, heavily used, blackened brass pipe fitting. I naturally concluded that it had been left behind by a tradesman, tasked with repairing and replacing a section of the store’s antiquated plumbing.

I caught the attention of my buddy behind the counter, nodded my head in the general direction of the anomaly, and asked “why is there an old chunk of pipe in the Leica case?”

Without even glancing toward it, he knew exactly what I was talking about. “That’s an old, screw-mount Leitz 90 Elmar,” he replied.

“Is it any good?” I inquired.

“Probably not,” replied my buddy.

He opened the cabinet, extracted the alleged lens, and handed it to me. I nearly dropped it through the glass Canon display case over which I stood. My brain had severely underestimated just how heavy an ugly little tube of solid brass and glass could be. I held it up to the light and witnessed its densely oxidized brass and black patina seemingly absorb all the ambient light in its vicinity. I rotated the focus ring, and to my surprise, the lens elements moved in and out. I spun the aperture ring, and the internal blades dutifully opened and closed.

Both repulsed and mesmerized, I screwed it to an LTM-to-M adapter I had in my bag, then mounted the combo on my Leica M9. Visually, it was the unholiest of unions — a device certainly capable of photographing Satan himself. No lens/body marriage ever looked so homely, ill conceived, or just plain wrong. But like the plot of a bad romantic comedy, repulsion turned to love. And like the plot of a bad porno, love came cheap. $65.

I’ll admit, the images it foisted upon the M9 sensor looked every bit as ill conceived and homely as the lens itself. They were soft, blooming, heavily vignetted, and weirdly colour-shifted. Plus, the lens seemed incapable of rendering more than 3 stops of dynamic range — no matter how contrasty the actual scene. Calling it a “character” lens would merely trivialize its many aberrations.

Several times, over the next year, I’d mount it to the M9 and snap off a couple of shots — wondering what subjects, if any, could possibly benefit from being photographed with a 1938 90mm f4 Elmar? Particularly when there’s a perfectly capable 1996 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit-M sitting beside it on the shelf? Obviously, unlike the Elmarit-M, I could mount the pipe on an old Leica III — but I possessed neither a 90mm viewfinder nor the will to bother. So the ugly little pipe fitting eventually got ostracized from the “good gear” cabinet, and into a box with some of Satan’s other photographic castoffs.

And there it sat… month after month… year after year… until a few weeks ago, when it finally realized its purpose: to protect me from myself.

Prior to my dual cataract surgeries, I was fearful that my photography style might change once I gained the benefit of sight. For the last several years, trees had no branches; architecture had no ornamentation; humans had no faces. Post-surgery, I can now see that trees do have branches; architecture does have ornamentation; and humans have taken to wearing face masks.

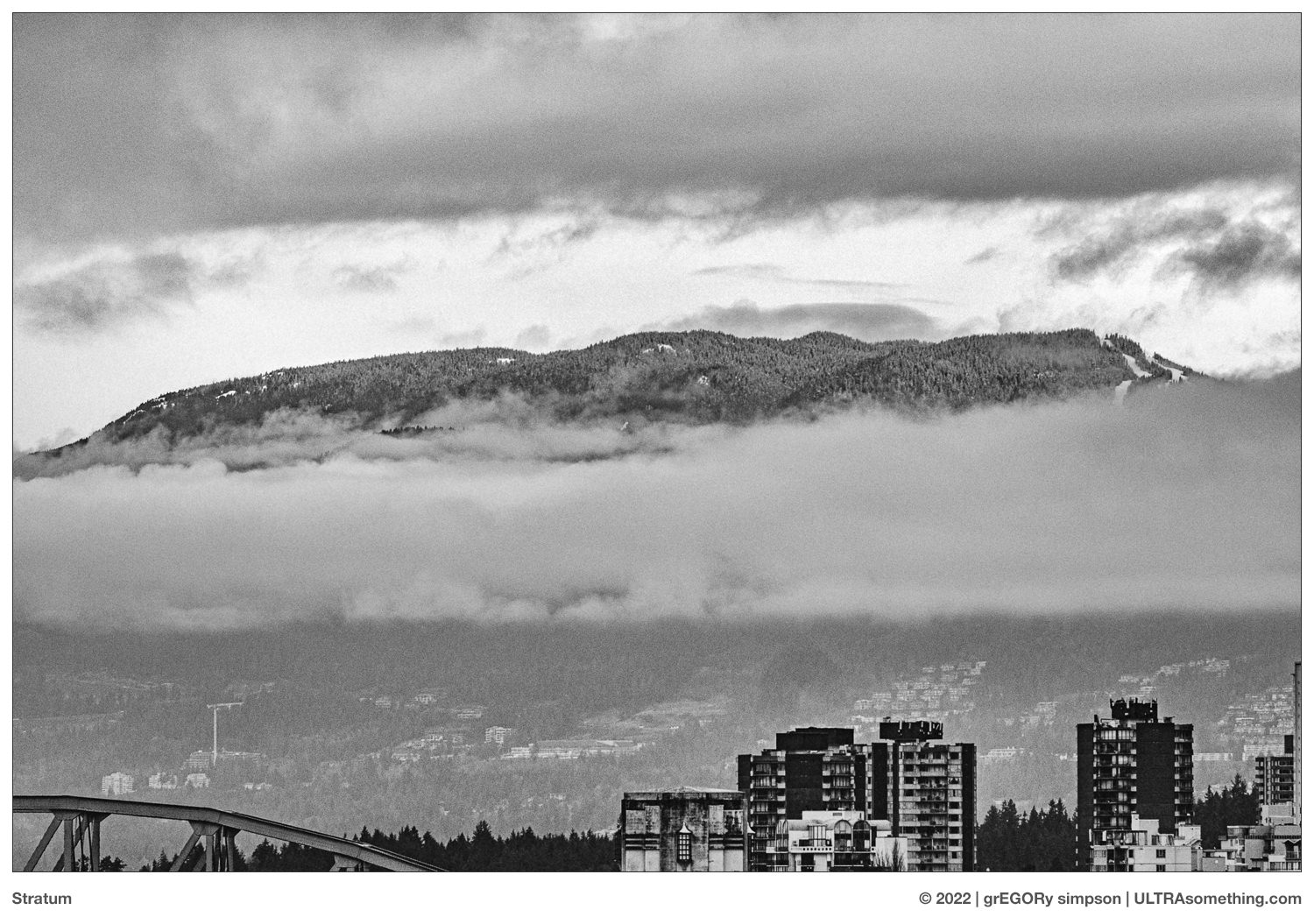

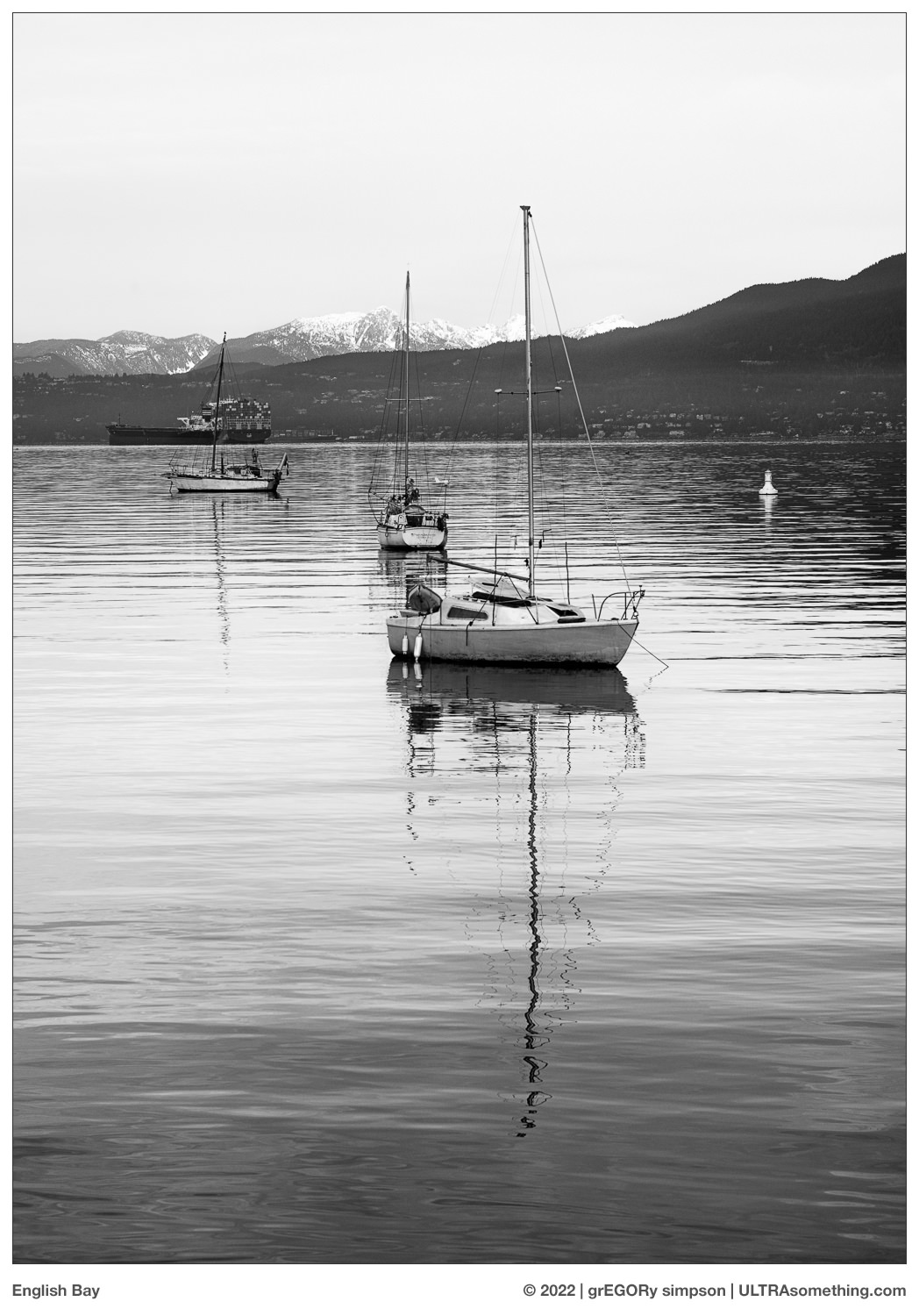

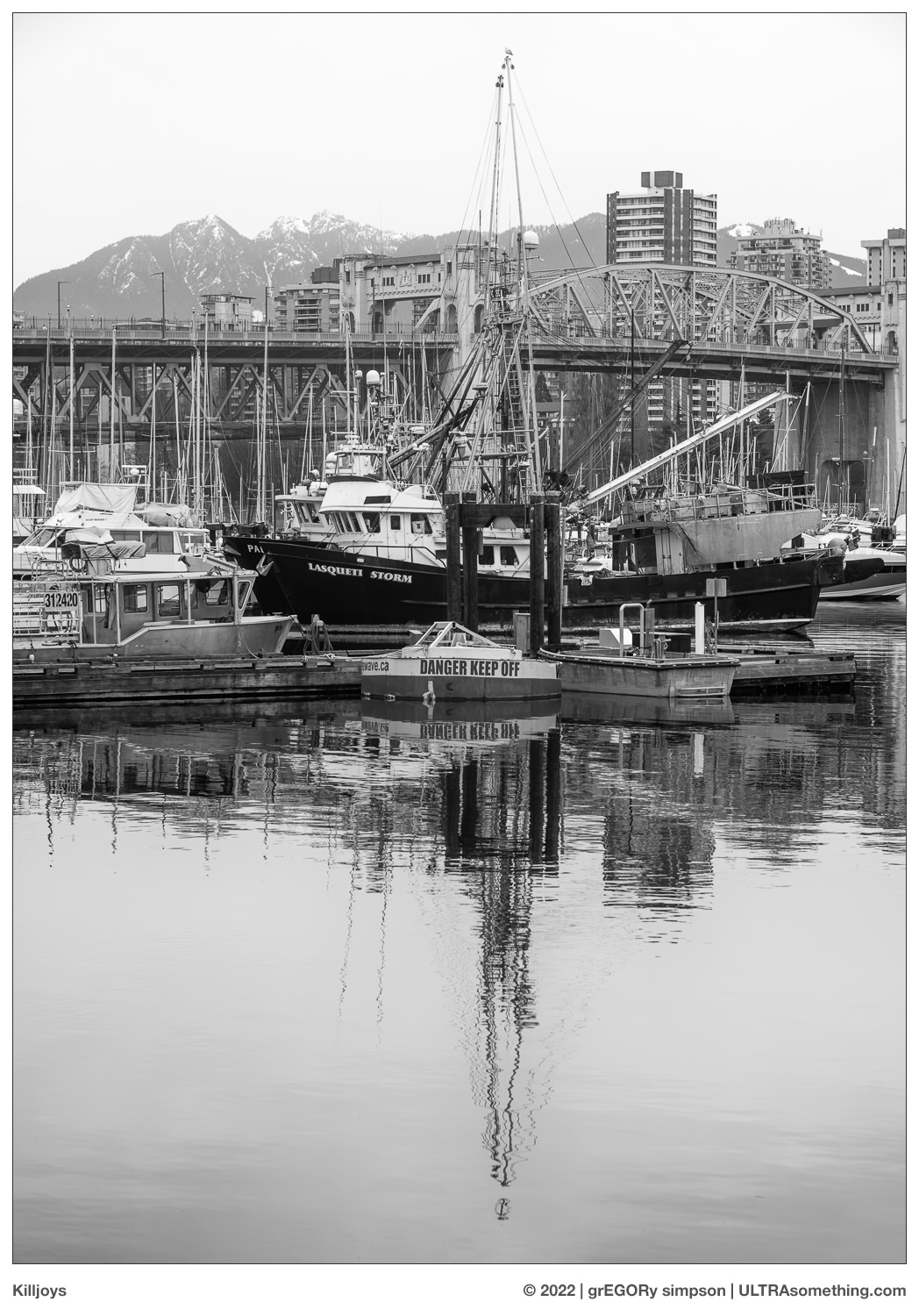

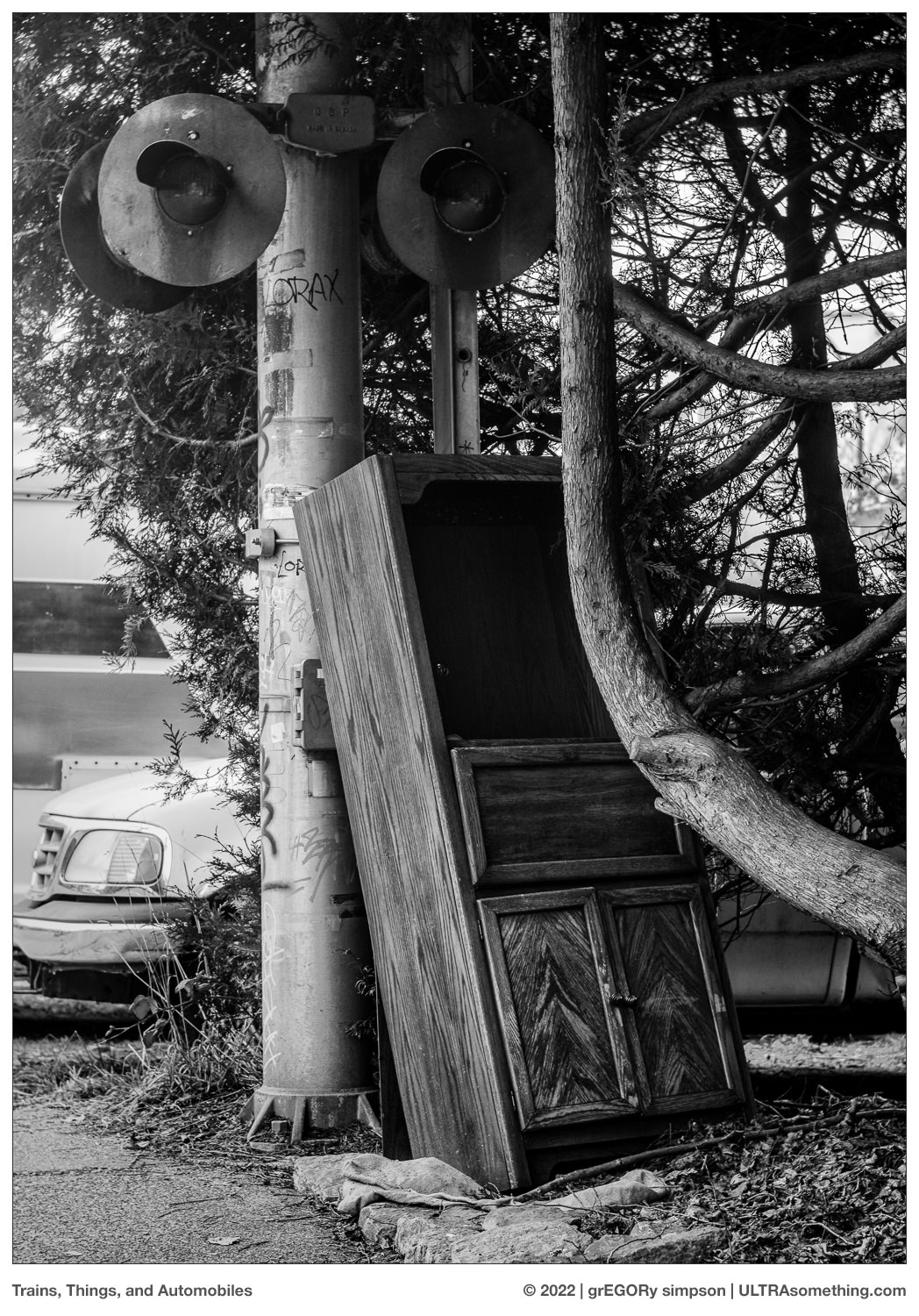

Sure enough, with my daily environment now awash in a rich display of detail, I felt compelled to photograph it — and the high-res, high-fidelity Leica M10 Monochrom seemed just the tool to use. It took but a single afternoon of snapping the most banal images imaginable for me to learn my pre-surgery fears were coming true. Gone were the metaphors — replaced by hackneyed shots of snowcapped mountains, and boats floating on a gently rippling sea.

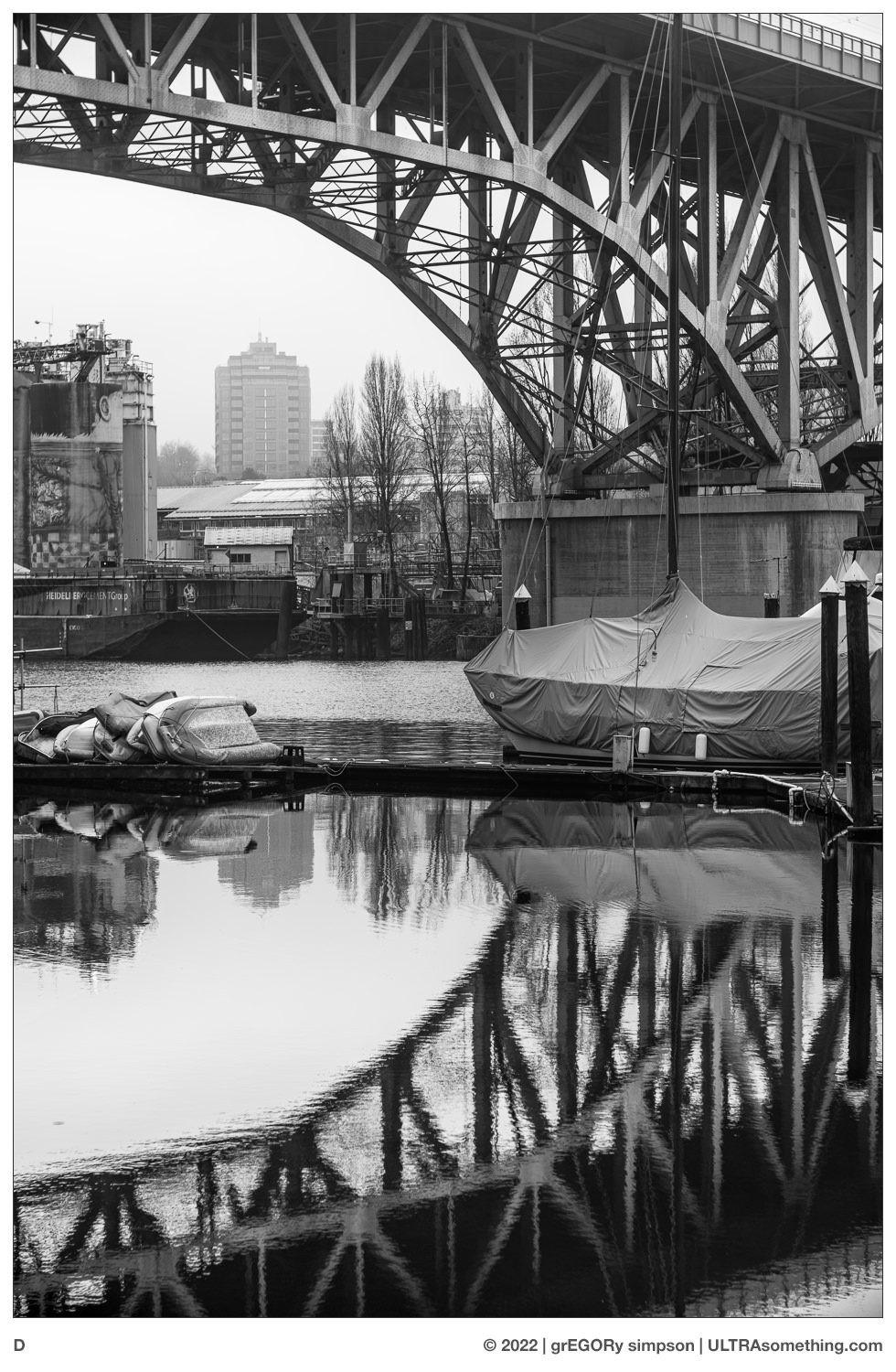

What I needed was a way to save me from myself. And it dawned on me that salvation might just lie in that old 90mm Elmar, sitting in the bottom of Satan’s drawer. Mounted to that same M10 Monochrom and tasked with photographing the vapidness to which I was currently drawn, it worked a treat. While it didn’t stop me from pointing my camera at scenes awash in splendid detail, it did stop my camera from recording all that surfeit precision — the type guaranteed to lead me insidiously down a path to some untoward belief that the “best” photo is the one which most sharply renders an aphid on the stem of some superfluous plant halfway across the frame from the actual subject.

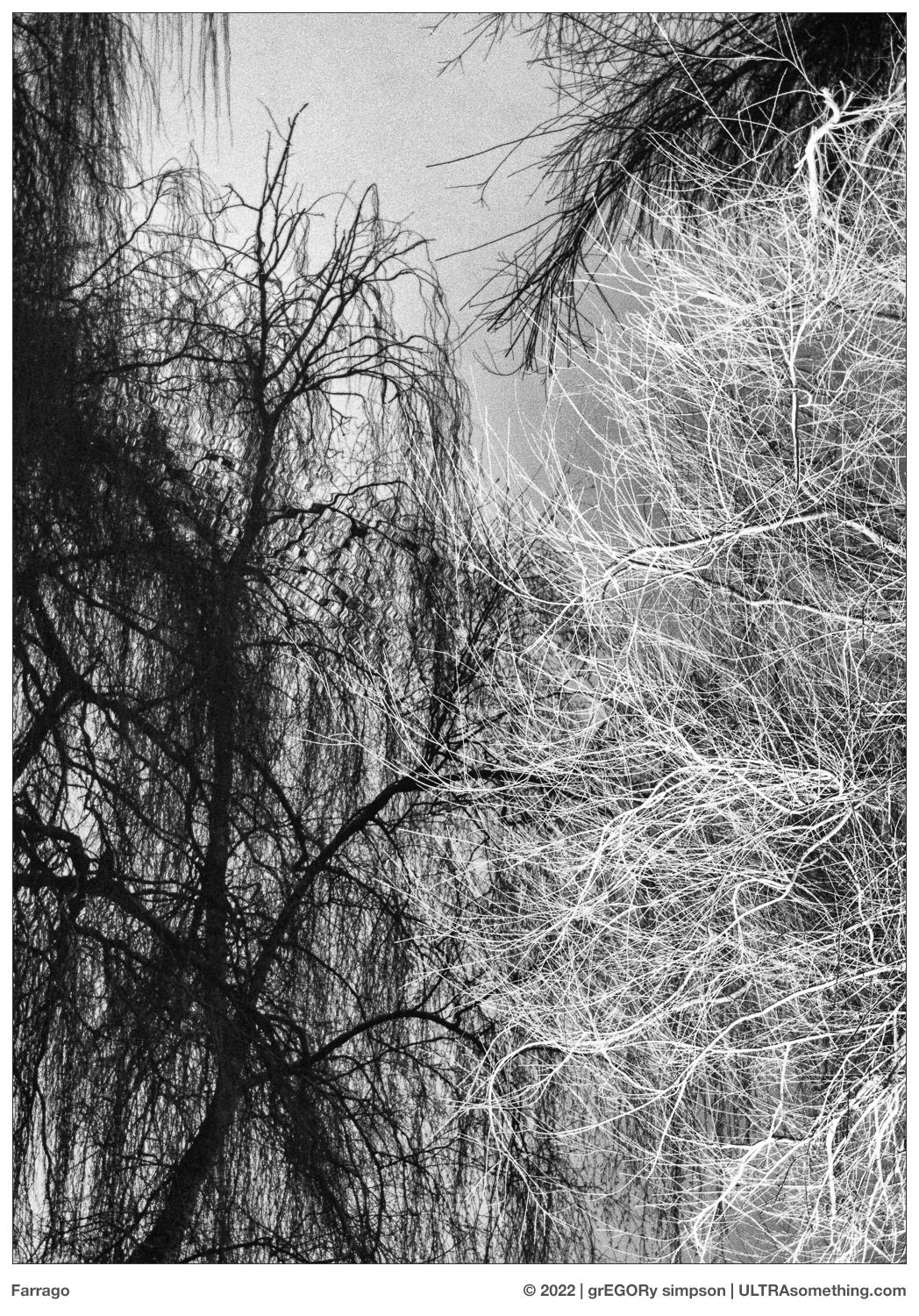

No matter what I point this lens at, it produces images as soft as a roll of premium toilet paper; with resolution that would strain to chart above 2 lines/mm on an MTF chart; and with the dynamic range of grey cement under a heavily overcast sky.

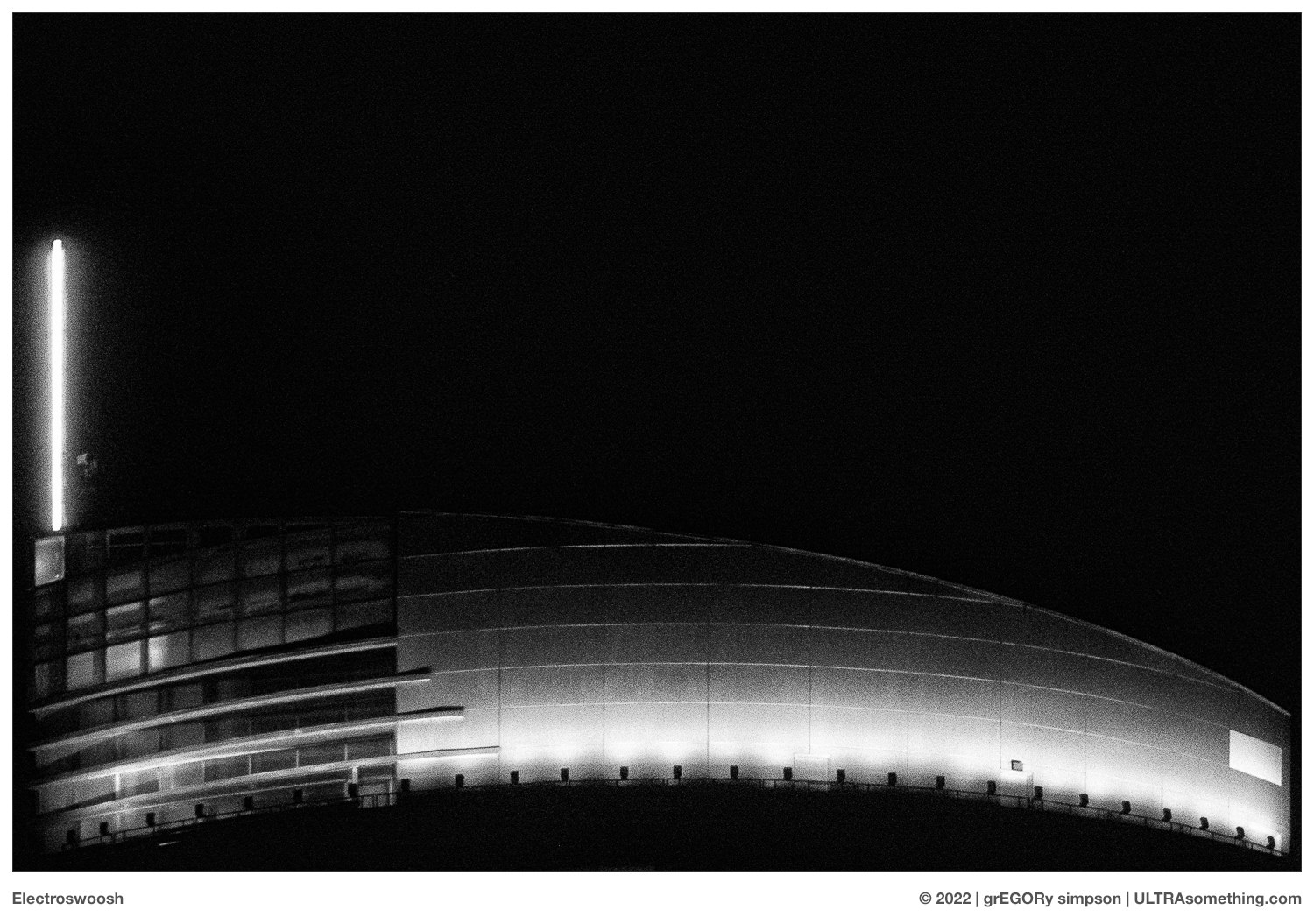

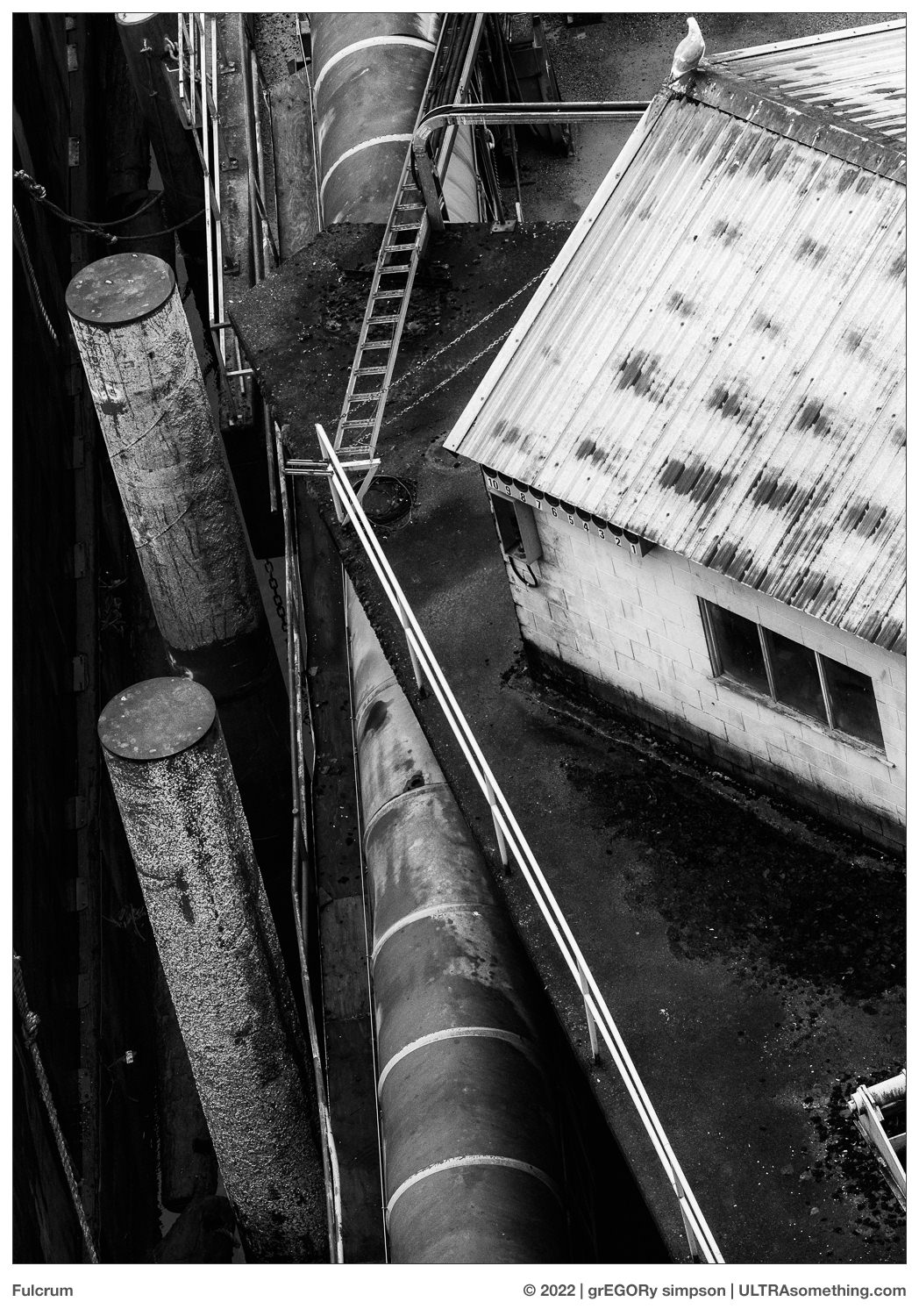

Though such characteristics may sound detrimental — and the out-of-camera images do look grotesquely horrendous — there are actually a couple of benefits. First, the inherent lack of resolution eliminates any point to pixel-peeping, and instead lets me concentrate on the more interesting aspects of a photo’s shape and form, and not its details. And second, the paucity of dynamic range makes the files highly malleable. Once I started shoving pixels around in Photoshop, I discovered I quite liked how this old lens saw the world. The very act of setting an image’s black-point and white-point spreads the limited collection of captured mid-greys widely apart — granulating any gradations to produce a rather organic grittiness. This results in an ‘old fashioned’ quality that’s entirely contrary to the technical accuracy favoured by today’s lenses. So while my photo subjects remained every bit as banal as the ones I shot that first afternoon, the actual photos became suggestions of banality, rather than full-on clinical examples.

Naturally, once I saw how successfully the pipe fitting mucked with the Monochrom’s fidelity, I wanted even less fidelity. And so it soon found its way onto the front of my Olympus OM-D E-M1 Mk3 — courtesy of not one but two lens mount adapters. There, the images took on even more grit.

I’m not sure how much longer I’ll remain enchanted by the fact that skies have birds, boats have names, and signs have words… but at least I know the patented lo-fi look of my photographs doesn’t need to suffer too much (even if the subject matter does). Maybe it’s finally time I got around to mounting this sucker on an old Leica III, where it truly belongs…

©2022 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THE PHOTOS:

Astute readers will notice that I’ve applied the apocryphal formula of “One dozen mediocre photos = one good photo” for visually populating this article. I’m pretty rusty on the whole notion of taking photos of things I can actually see, so there might be a lag until I regain enough skill to take some good photos, and thus reduce the quantity I need to publish.

As suggested by the article, everything was shot with either the Leica 10 Monochrom or the Olympus OMD E-M1 MK3. For those that actually care, “Fulcrum”, “Stratum”, “Farrago” and “Electroswoosh” are the Olympus shots. Everything else is the Monochrom… well, except the product shot, obviously.

REMINDER: If you’ve managed to extract a modicum of enjoyment from the plethora of material contained on this site, please consider making a DONATION to its continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site. Serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls — even the silly stuff.

Lovely storytelling, EGOR, and gorgeous images!

When you’ve got the eye the gear will do the job! And you certainly have!

Thanks, Peter. Not exactly my usual photographic subjects, I know… but then nothing’s exactly been “usual” since the start of COVID, has it? 😉

The 90mm f4 Elmar is probably the only bit of genuine Leica glass that is somewhat close to trivially affordable to me. Or maybe a collapsible 50mm f3.5 with a little bit of fungus and dusts.

I should get one for my Zorki I that is gloriously dressed up in black paint and masquerading as a Leica II. I recently acquired a KMZ turret finder with an 85mm setting, so that is close enough and so the viewfinder is covered.

But what what to do about the Zorca’s rangefinder which has it’s own case of cataracts and which is only visible if pointed directly at a light source? Zone focussing is a cinch with my Jupiter 12, but I can see such a strategy failing miserably with the Elmar. Then again sharp focus is hardly the object of this particular exercise, is it?

I could always strap it to the front of my Panasonic GF1, crop factor be damned, and even use the aforementioned turret finder. Hell, I could put a red dot sticker on the front and really play let’s pretend. But I already have a surplus of soft contrast-free lenses and adapters that I can use with that system.

I suppose I could always start grinding my own lenses and installing them in cardboard tubes like Miroslav Tichy, who has recently become another of my photographic icons. German engineering is overrated anyway!