“We’re doomed!” exclaimed the painters — scurrying about helter-skelter, tripping over easels and slipping comically in spilled paint as they ran for the hills. It was the mid-19th century, and the cause of all this commotion was a little thing called “photography.” Paul Delaroche, upon first seeing a daguerreotype, was said to declare that “from today, painting is dead.” The fear, of course, was that no one would ever want to purchase an inexact rendering of a particular subject when, instead, they could buy an exact one.

“We’re doomed!” exclaimed the painters — scurrying about helter-skelter, tripping over easels and slipping comically in spilled paint as they ran for the hills. It was the mid-19th century, and the cause of all this commotion was a little thing called “photography.” Paul Delaroche, upon first seeing a daguerreotype, was said to declare that “from today, painting is dead.” The fear, of course, was that no one would ever want to purchase an inexact rendering of a particular subject when, instead, they could buy an exact one.

The popularity of this view was predicated on the supposition that paintings must be representational and realistic by nature. Salon painters bore the greatest burden of this belief because, for Mr. & Mrs. Joe Public, commissioning a photographic portrait was a cheaper, faster and more accurate alternative to having one’s portrait actually painted.

But those painters who believed their passion was less a technical endeavor than a creative one, rose to the challenge. They developed new styles and new models for painting that went far beyond the more literal desires of the salon painter. And so art and photography formed a sort of “truce.” Paintings became impressionist, cubist, surreal and abstract while photography was allowed to satisfy the more mundane documentary needs.

From this divide arose a rather interesting question — is photography actually “art?” Photography was framed and hung upon a wall. Was that enough? Unlike a painter, anyone with the financial means to purchase the necessary equipment, develop a basic knowledge of chemistry, and partake in some rudimentary training could become a photographer. With a barrier to entry so low, could photography really be called “art?”

In the early 20th century, it was that very ease of entry that lured many would-be painters and artists into photography. The new generation didn’t necessarily subscribe to the belief that photography must be purely representational. Photographers began to experiment with all manner of techniques, lenses, lighting, compositional tricks and darkroom manipulations to create images that bore no resemblance to simple literal portraits or landscapes. Like the little brother who didn’t know his place, photography was once again dabbling in the painter’s domain — challenging preconceived notions and developing bold new visions. Only now, photography wasn’t seen as a threat to painting, but an adjunct.

Photography had finally gained widespread acceptance as an actual art form. It had not replaced painting as many initially feared, but had instead found its own niche within the rarified air of the art gallery. Some even argue that the invention of photography reinvigorated painting and, in turn, painting’s daring new directions gave photography a cultural boost it might not ordinarily have seen.

While many photographers were striving for acceptance within the art community, there existed a ragtag group of adventurers, revolutionaries and raconteurs who saw an entirely different purpose for photography. They saw photography as a way to enlighten, educate and change perceptions. These were the photojournalists. To them, nothing could be more banal than a photograph taken specifically to hang upon a gallery wall. What would that accomplish? What could it change? Unlike the artists, photojournalists didn’t rebel against the “documentary” nature of photography — they ran with it. And there was no shortage of periodicals willing to run with them. This was the day of Paris-Match, Look, Life, Picture Post and others. For photojournalists, photography was not art. It was language — a new way to tell the stories of a rapidly changing world.

While many photographers were striving for acceptance within the art community, there existed a ragtag group of adventurers, revolutionaries and raconteurs who saw an entirely different purpose for photography. They saw photography as a way to enlighten, educate and change perceptions. These were the photojournalists. To them, nothing could be more banal than a photograph taken specifically to hang upon a gallery wall. What would that accomplish? What could it change? Unlike the artists, photojournalists didn’t rebel against the “documentary” nature of photography — they ran with it. And there was no shortage of periodicals willing to run with them. This was the day of Paris-Match, Look, Life, Picture Post and others. For photojournalists, photography was not art. It was language — a new way to tell the stories of a rapidly changing world.

For one brief moment these disparate disciplines of painting, reporting, art and photography settled into a sort of uneasy equilibrium. It wouldn’t last for long.

~ + ~

“We’re doomed!” exclaimed the photojournalists — scurrying about helter-skelter, tripping over a pile of Leicas and slipping comically in puddles of fixer as they ran for the hills. It was the mid-20th century, and the cause of all this commotion was a little thing called “television.”

René Burri, back in a hotel lobby after photographing a story for Paris-Match, was writing captions and packing up his film to send off. He glanced up at the television and saw that same story — his story — playing on the news. “Don’t watch this!” he shouted to those in the lobby, “You’ll see it in Paris-Match on Monday!” The fear, of course, was that no one would want to wait a week to look at a few representational photos from an event when, instead, they could watch the entire thing, like a motion picture, on the very day it unfolded.

The popularity of this view was predicated on the supposition that photojournalism is nothing more than a chronicling of events — a document of facts recorded without context or meaning. Straight news photographers, more than any others, likely suffered the burden of this belief. For Mr. & Mrs. Joe Public, it was easier to feed their eyes with TV images while they fed their bellies with TV dinners.

The popularity of this view was predicated on the supposition that photojournalism is nothing more than a chronicling of events — a document of facts recorded without context or meaning. Straight news photographers, more than any others, likely suffered the burden of this belief. For Mr. & Mrs. Joe Public, it was easier to feed their eyes with TV images while they fed their bellies with TV dinners.

But those photojournalists who believed their passion was less a technical endeavor than a creative one, rose to the challenge. They sought greater insight and developed new ways to tell stories through photography. The best photojournalists realized they possessed a very important power — the power to freeze time. Their task was to find that one perfect image, expression or composition that could deliver the news, the commentary and the meaning all within a single captivating shot.

Paradoxically, the creativity of photojournalists only reinforced photography’s artistic provenance. No longer were galleries the sole domain of Man Ray, Moholy-Nagy or the f/64 group. They were being joined, in increasing numbers, by such documentary-style photographers as Cartier-Bresson, Frank and Friedlander. Surprisingly, an explosion in the number of amateur photographers helped further cement the notion that photography was art. By further democratizing photography, people gained appreciation for the dynamic visual impact of an Ansel Adams print when compared with their own vacation shots. They could plainly see that their holiday party portraits failed to glow with the chic cool of a Richard Avedon. To Mr. & Mrs. Joe Public, who owned a Kodak Instamatic and developed their film at the local pharmacy, good photography seemed like “magic” and the practitioners “artists.”

Photography had matured, and now ran the gamut from folk artists to fine artists. And for one brief moment all the various disparate photographic disciplines settled into a sort of uneasy equilibrium. It wouldn’t last for long.

~ + ~

“We’re doomed!” exclaimed all the professional photographers (and not just the photojournalists) — scurrying about helter-skelter, tripping over tripods and slipping comically in pools of their own salty tears. It was the early-21st century, and the cause of all this commotion was a little thing called “digital.” Magazines and newspapers fell by the wayside in favor of television and the internet. Television channels multiplied like rabbits, all demanding more video content. Broadband technology replaced dial-up modems, further fuelling commercial demand for online video content. Galleries and museums fell prey to budget cuts and photos became something you viewed on a computer monitor, rather than in print.

In a blink of an eye, the technological distinctions that once separated professional photographers from amateurs disappeared. Not only did the family shutterbug gain access to the same tools and techniques that the professional photographer used, but he was also granted free admission to the latest and greatest trend in publishing: the internet.

In a blink of an eye, the technological distinctions that once separated professional photographers from amateurs disappeared. Not only did the family shutterbug gain access to the same tools and techniques that the professional photographer used, but he was also granted free admission to the latest and greatest trend in publishing: the internet.

Digital technology finally, fully and (some may say) fatally democratized photography. Gone was the need to learn the fine craft of retouching with bleach. Poof went the zen art of pre-visualization and the zone system. No longer must a photographer become a dexterous master of the shadow puppet — dodging and burning prints beneath the light of their enlargers. The family shutterbug needed only to point, click and upload. Software replaced knowledge. Launch an app, click a button, see an effect. Don’t like it? Try another! Experimenting with different photographic effects took seconds, not weeks. Like a photo? Push another button and order a print the size of a billboard. In the bourgeois mind of the democratized photographer, bigger always equals better.

All over the world, professional photographers are moaning like a bunch of 19th century painters. And for what? Because any amateur can now take a photo that’s the technical equivalent of a professional’s? Maybe that matters if, like the salon painters of yore, you believe technical accuracy equates with photographic quality. I don’t.

Perhaps our treatment of photography as an art has done it a great disservice. Art demands that the viewer appreciate the technique behind it. It calls attention to its technical merits. A good photograph should never do this. Rather, it should just be.

The photojournalists had it right — partially. Photography is indeed a language. But it’s not the sort that lends itself to a novel, a journal or even a short story — that’s the parlance of video. The language of photography is the language of the poet.

Like a poem, a still photo is succinct. Like a poem, it can say as much by what it doesn’t say as by what it does. Like a poem, there is metaphor. Like a poem, there is rhythm and there is nuance. Like a poem, there are layers, multiple meanings, passion and abstraction.

Like a poem, a still photo is succinct. Like a poem, it can say as much by what it doesn’t say as by what it does. Like a poem, there is metaphor. Like a poem, there is rhythm and there is nuance. Like a poem, there are layers, multiple meanings, passion and abstraction.

In 1951, Robert Frank told Life Magazine “When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.” Frank had it figured.

Few things are as democratic as language. Most of mankind can communicate verbally and a substantial majority can communicate via the written word. But just because everyone can speak doesn’t mean everyone is a story teller. The fact most people can write doesn’t mean they’re all poets. So if everyone can now take sharp, contrasty, crisply focused photographs does that mean everyone is a photographer? Good photographs require more than technique. They require more than technical competence. They require vision. They require a way of seeing a greater whole and encapsulating it into a single photo — like a poet. Not every photograph is a poem — just those taken by poets.

Photography does not begin with sharpness and end with exaggerated micro contrast. Rather, it begins with exploration and it doesn’t end at all. Photography is not limited to a single type of poem. There are epic poems, romantic poems, elegies and odes. There are allegories, sonnets and classical poems. Some photographers cross genre. Others specialize. In my own photography, I often strive for a kind of beat poetry. I fear I come closer to limerick. But at least there’s rhythm.

It’s the same as the situation that faced painters 150 years ago — those photographers who view their work as a creative endeavor, rather than a technical one, will persevere. And what of those photographers who can’t imagine photographing their pet cat without the highest resolving, lowest noise sensor fronted with the sharpest, most distortion-free, fastest, highest contrast lens that money can buy? Let’s just say that no one has ever judged poetry by the quality of the pen that wrote it.

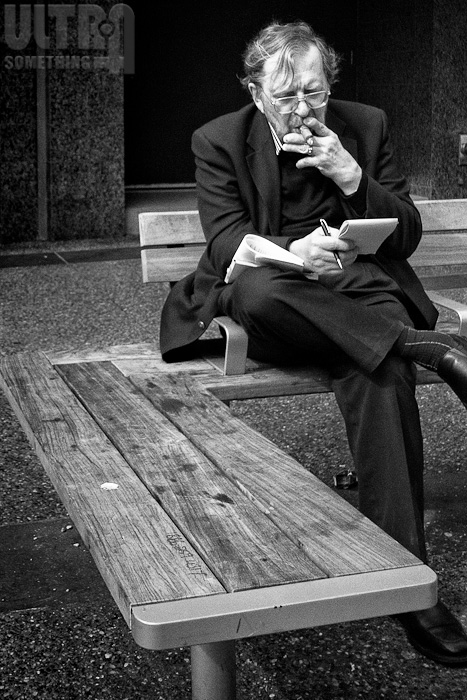

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “Hot and Fresh,” “Cigar Man” and “Cigarette Woman” were all shot with a Panasonic DMC-GH2 and a Voigtlander 15mm f/4.5 Super Wide Heliar lens. “Photographer’s Haute Couture” and “Parade – Anticipation of Youth” were shot with a Leica M9 and a Voigtlander 75mm f/2.5 Color-Heliar lens. “Parade – Apathy of Age” was shot with a Leica M9 and a Leica 28mm f/2 Summicron lens.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.

Great commentary knitting together the big “art/photography narrative” in a way that my small mind can comprehend – it bears reading again, and again. I particularly liked the poetry metaphor – “Photography is not limited to a single type of poem” probably because it’s broad enough to encompass my photography – which would be the rhyming couplet. Great photos – Pizza Dude and Penguin Woman are fabulous, while Kilted Drummer is timeless.

Excellent, Exactly so….

It is art that saved the professional photographer. Anyone can take a picture, but only a photographer can add the soul of the of the photograph.

Thank you, Egor! Great article.

Greg

Great article. Enjoyed the photos.

“Photography does not begin with sharpness and end with exaggerated micro contrast.”

Egor.

Thank you once again for opening my eyes to my own reflection.

I have images of my niece (age7) at a wedding that “technically” fail on all sorts of levels. Composition, out of focus, overexposed; and yet to me, they represent some of the most satisfying images I have taken of her, because they show her doing what she does and who she is. They echo your reoccuring theme, images you take for yourself vs. for others.

I see her in the drummer boy. You can dress me up, but I’m still wearing my trainers. (sneakers)

Jason the humble

[…] as each tends to pick a side and adhere to it at all cost. Last year, in an article entitled More Poe than Van Gogh, I proposed an alternative view that generated substantial internet discussion, but ultimately did […]

Wow. You explored and explained the question “Is photography art?” better than Susan Sontag did in a whole book of hers…

Wolfgang: Maybe. But only if you don’t follow-up with the question, “Is poetry art?” Then I’d have to start all over again…