What’s great about trilogies, is that you know precisely how many instalments you’ll need to endure… unless we’re talking about George Lucas, who has obviously deemed the dictionary to be a purveyor of fake news.

Still, just because there are three of something, it doesn’t mean you need to consume them all. Which — Lucas example extended — is exactly what happened with me and the Star Wars “trilogy.” I nodded off during the first film; never saw the second (or third, fourth, fifth, sixth, etc); and have been shunned by my technology coworkers for decades since. So I’d like to thank the small smattering of ULTRAsomething’s larger smattering of readers who’ve soldiered through to this, the final chapter in the Folly Trilogy — a trio of articles discussing “taking photos with cameras that are utterly inconsistent with modern visual tastes or with 21st century photo dissemination techniques.”

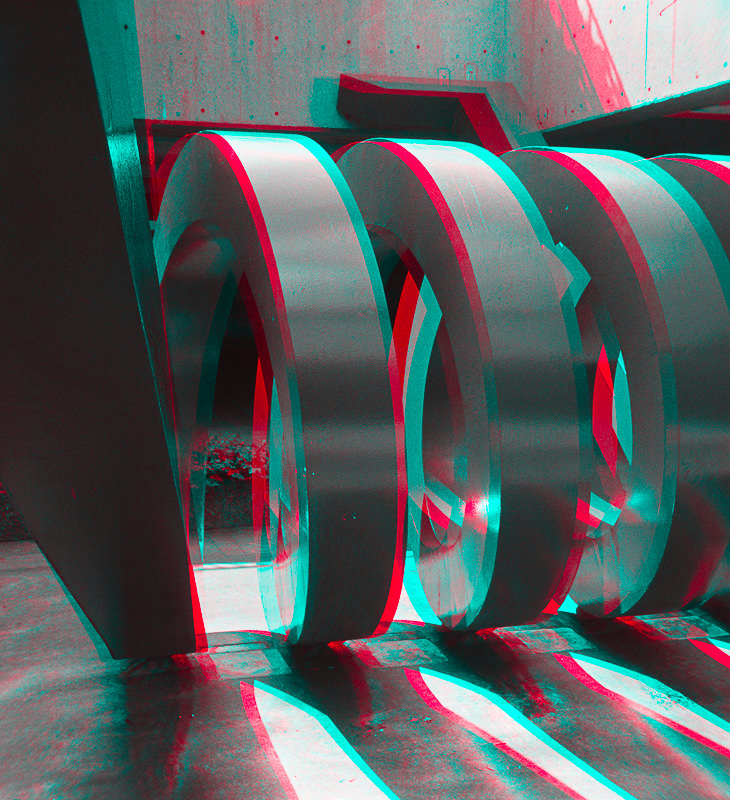

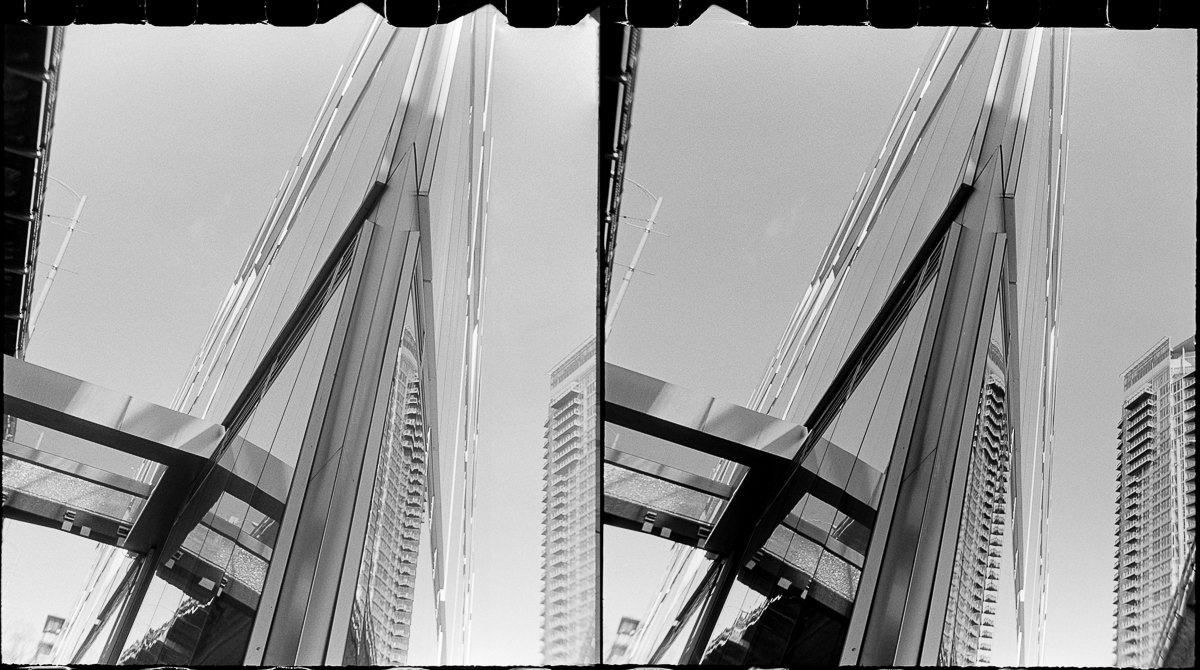

The first camera in this trilogy, the Kodak Stereo camera, qualifies as “folly” because its images, while likely to engage with an audience, are kept from doing so thanks to a 200 year dearth of suitable stereo viewing and distribution methodologies.

Unlike the Kodak Stereo camera, the second camera — the Pinsta — produces images that can be easily viewed and distributed through traditional means — but it succumbs to “folly” because I, the photographer, can’t be bothered to spend the inordinate amount of time and effort required to produce a single decent photograph — much less a collection.

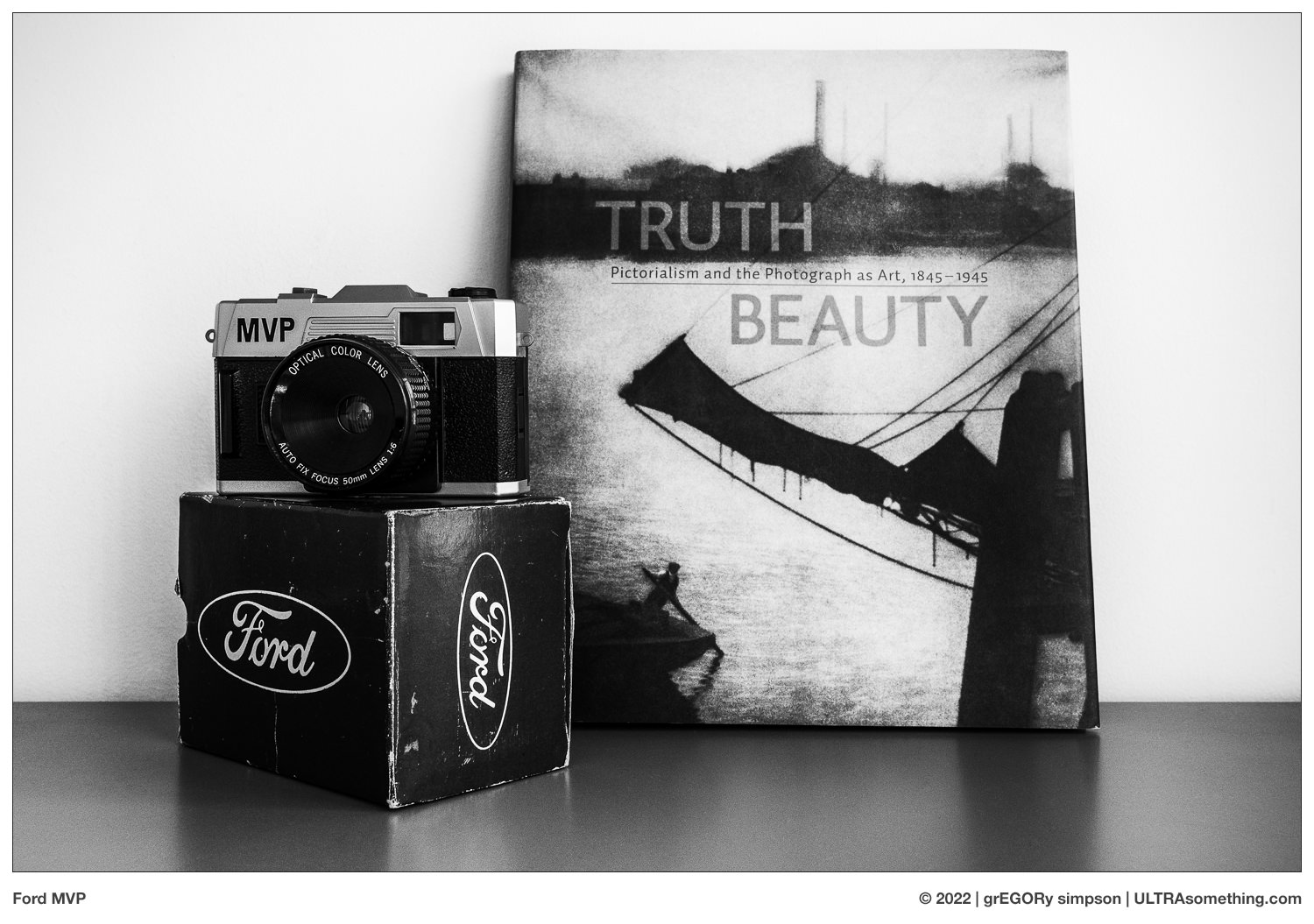

The third and final camera in the Folly Trilogy — the Ford MVP — is easy to carry and enjoyable to shoot (unlike the Pinsta); while producing standard 35mm images (unlike either the Kodak or the Pinsta). Unfortunately, the Ford MVP is guilty of looking more like a camera than acting like one. So cheaply made, it makes the build quality of Lomography cameras look like Hasselblads. And its image quality? No reason to change the metaphor, because it also makes the output of a Lomography camera look like a Hasselblad. If you ever wanted to smear a lens with Vaseline to get a dreamy effect, but didn’t have any Vaseline handy, this is the camera to reach for.

Obviously, Ford Motor Company didn’t make this camera, but they did slap their logo on the box — once offering it as incentive for customers to pony up for a new pony car. It’s from the same dubious lineage as the more widely known Time Magazine and Sports Illustrated cameras, which also served to sweeten the perceived value of parting with one’s cash. Unlike those zine cams, which had faceplates imprinted with the words “Time” or “Sports Illustrated”, the Ford is emblazoned with the letters “MVP”. Why? I have no idea, but I’m using it as a motivational tool. Preferable, too, is Ford’s decision to give it a swanky “chrome” body, which definitely out-hips those boring black magazine variants.

I’m guessing the camera dates from around the mid-1980’s, which corresponds precisely with my time at Ford Motor Company — though my job developing Ford’s high-end, acoustically-tuned, premium/branded sound systems left me ignorant of the mechanizations of Ford’s marketing “brains.” This little bit of Egor trivia is precisely why my friend — one of the few people aware of my automotive past — leapt at the chance to connect the dots, and gifted me with a Ford MVP that she stumbled upon in a Portland camera shop.

Belying a body made from Fisher-Price grade plastic, and a rewind crank that falls apart if you turn the camera upside down, the MVP sports a 50mm lens with an actual glass element. It even provides a modicum of exposure control via its pictograph-based aperture dial — its odds of relevancy depending, obviously, on your choice of film speed. Rumour has it the camera’s one and only shutter speed is 1/100s — which I figure is probably correct within an order of magnitude or two.

The MVP is much heftier than I expected, which gives an impression of quality — though one that’s been debunked by various websites, which reveal the presence of a lead weight placed in the bottom of the camera to produce exactly this illusion. I was tempted to disassemble mine to confirm the weight’s actual chemical compound, but given the build quality of the rewind crank, I opted not to risk removing any screws from any plastic.

The bottom of the camera proudly states “Made in Taiwan,” though I have yet to uncover its actual manufacturer, or who was responsible for its development. Not that it really matters, since designing butt-simple film cameras isn’t rocket science; much less automotive engineering.

The better question is “who, in Ford’s marketing department, thought this would make a good promotional item?” Any glee a customer might have felt pulling this from their bag o’ new car swag, would surely dissipate once they drove that new Mustang to the Fotomat™ kiosk and picked up their prints.

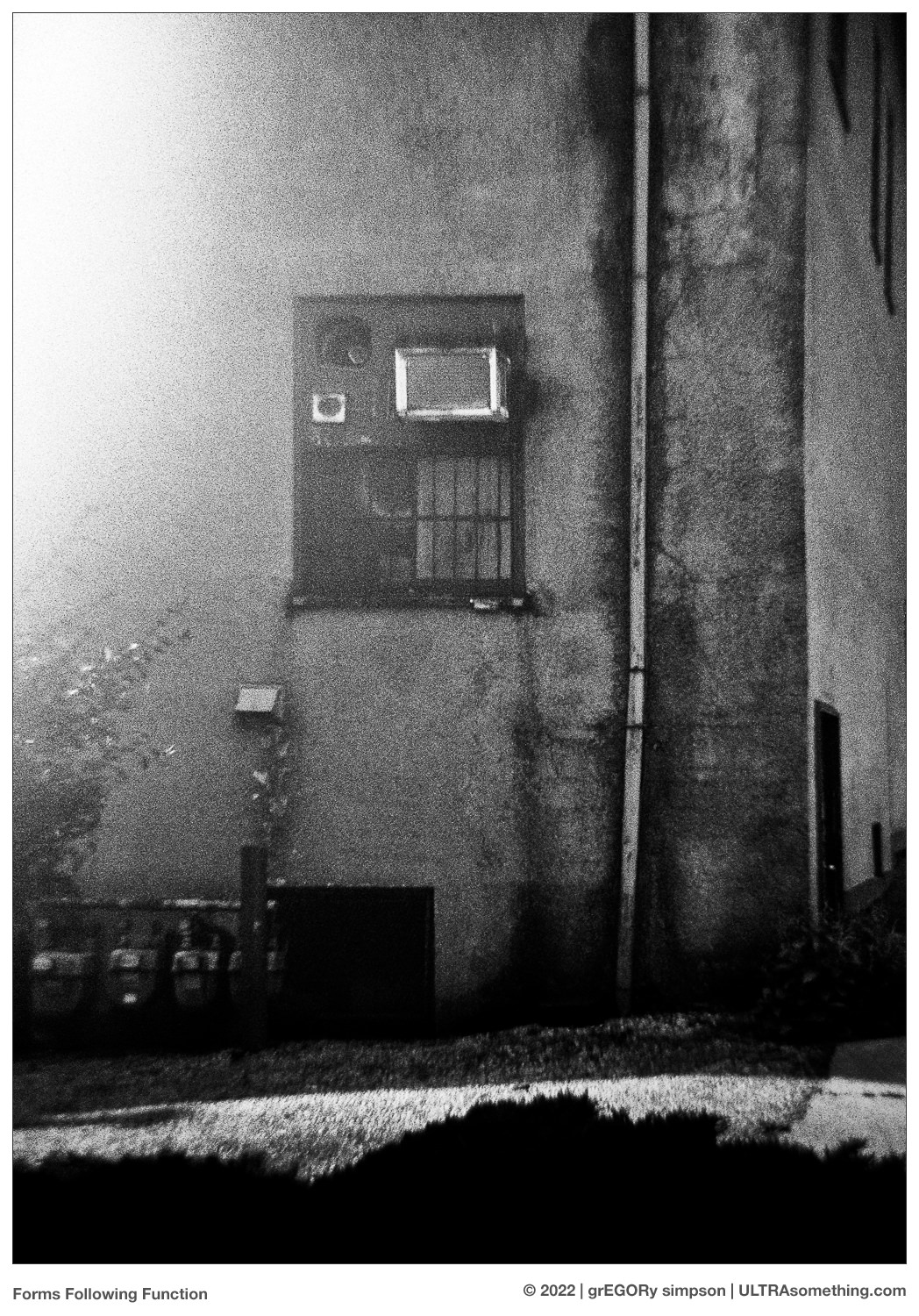

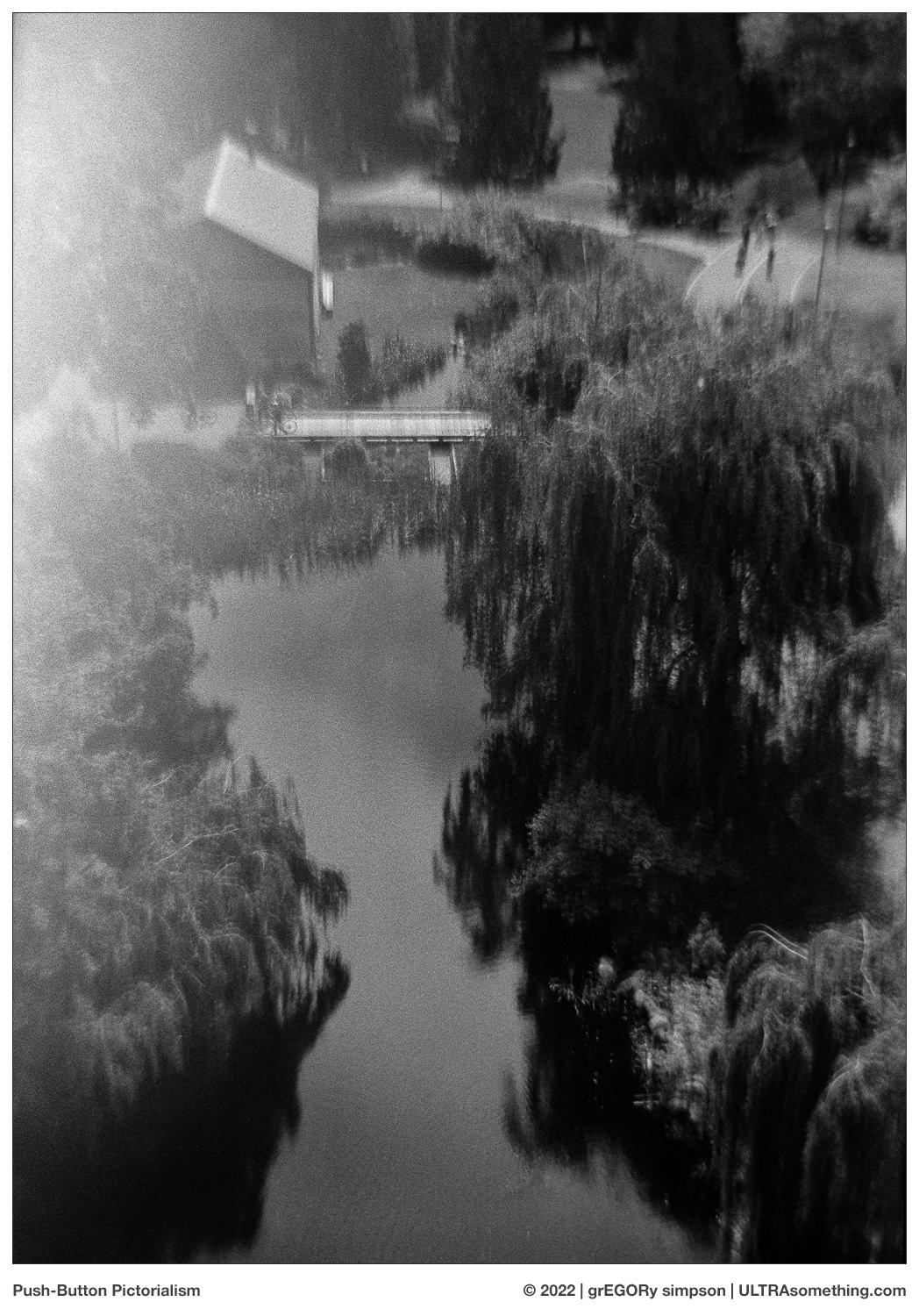

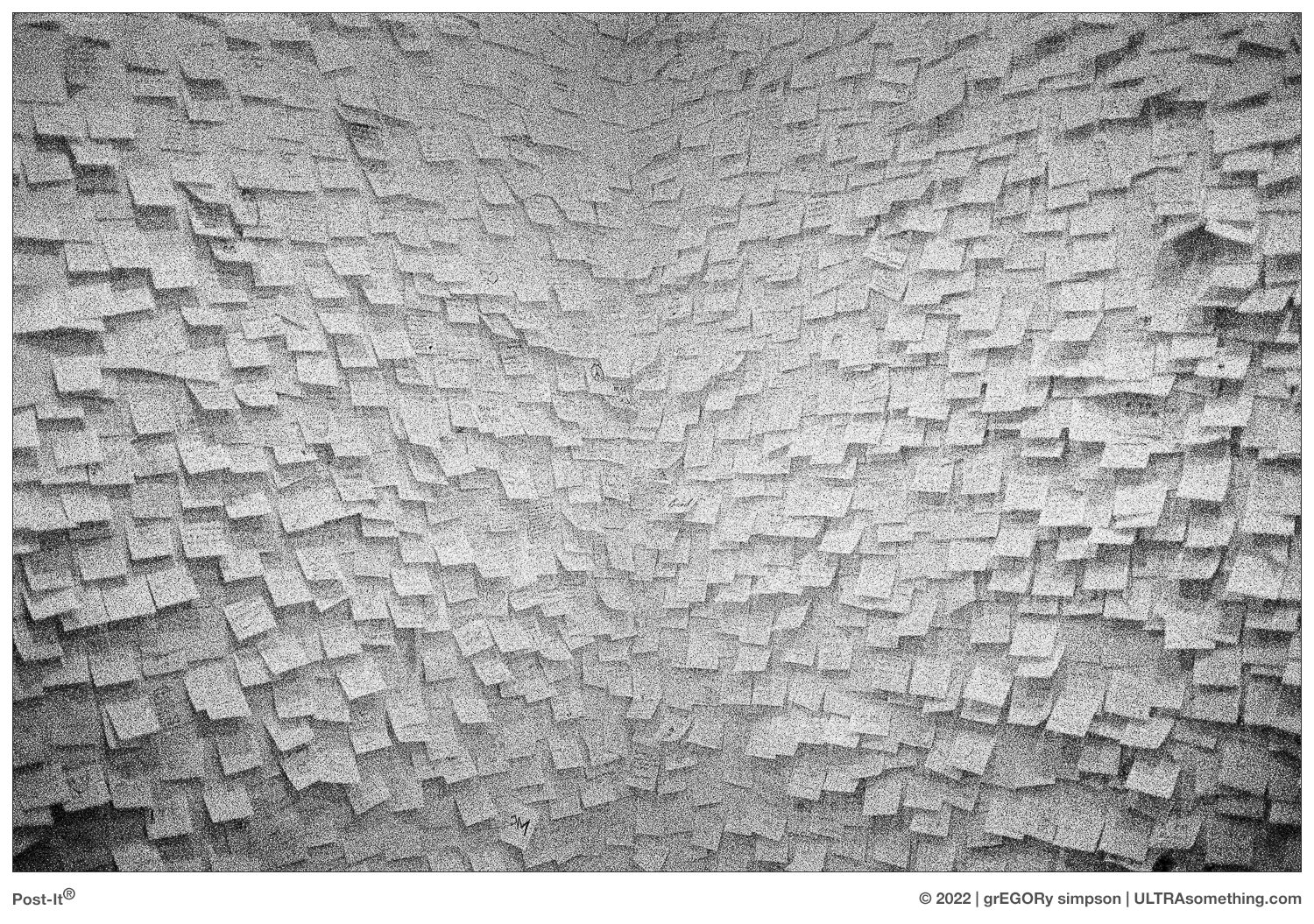

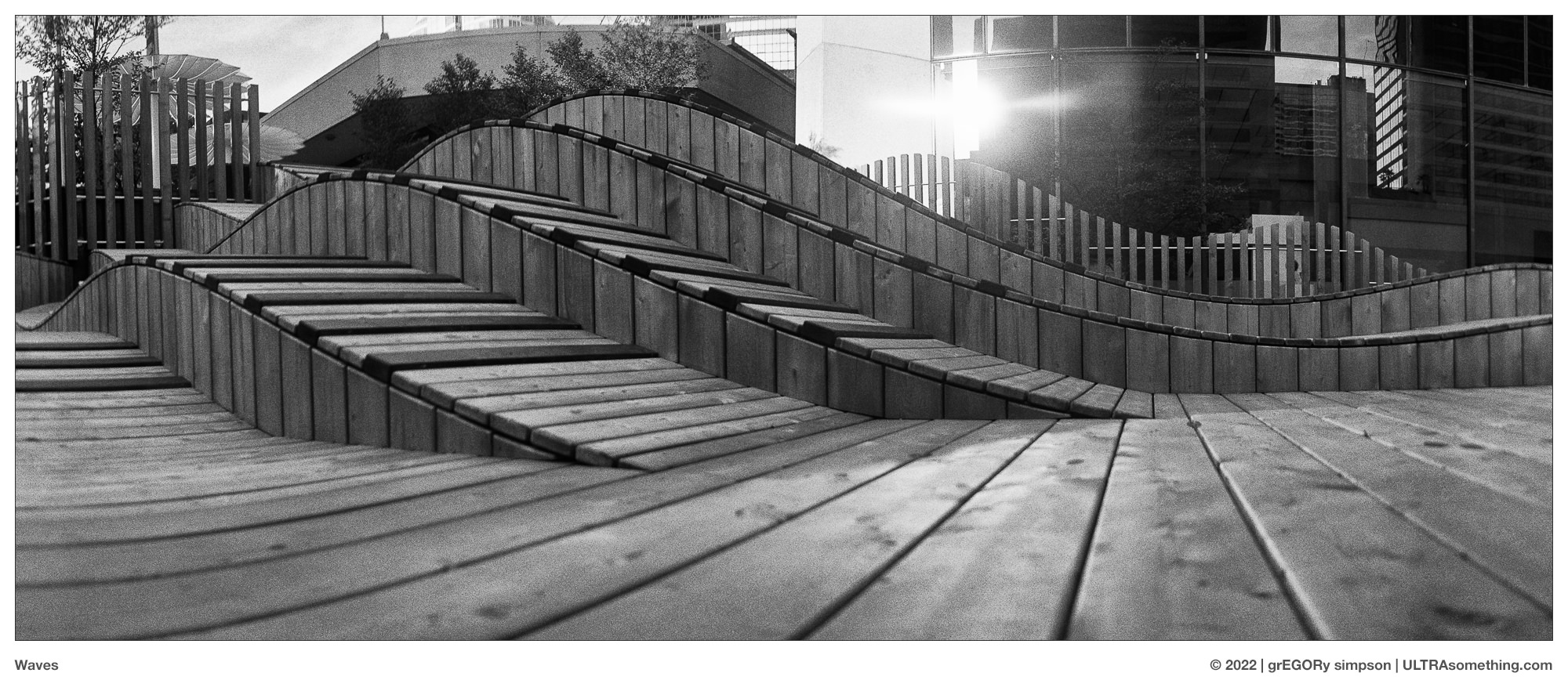

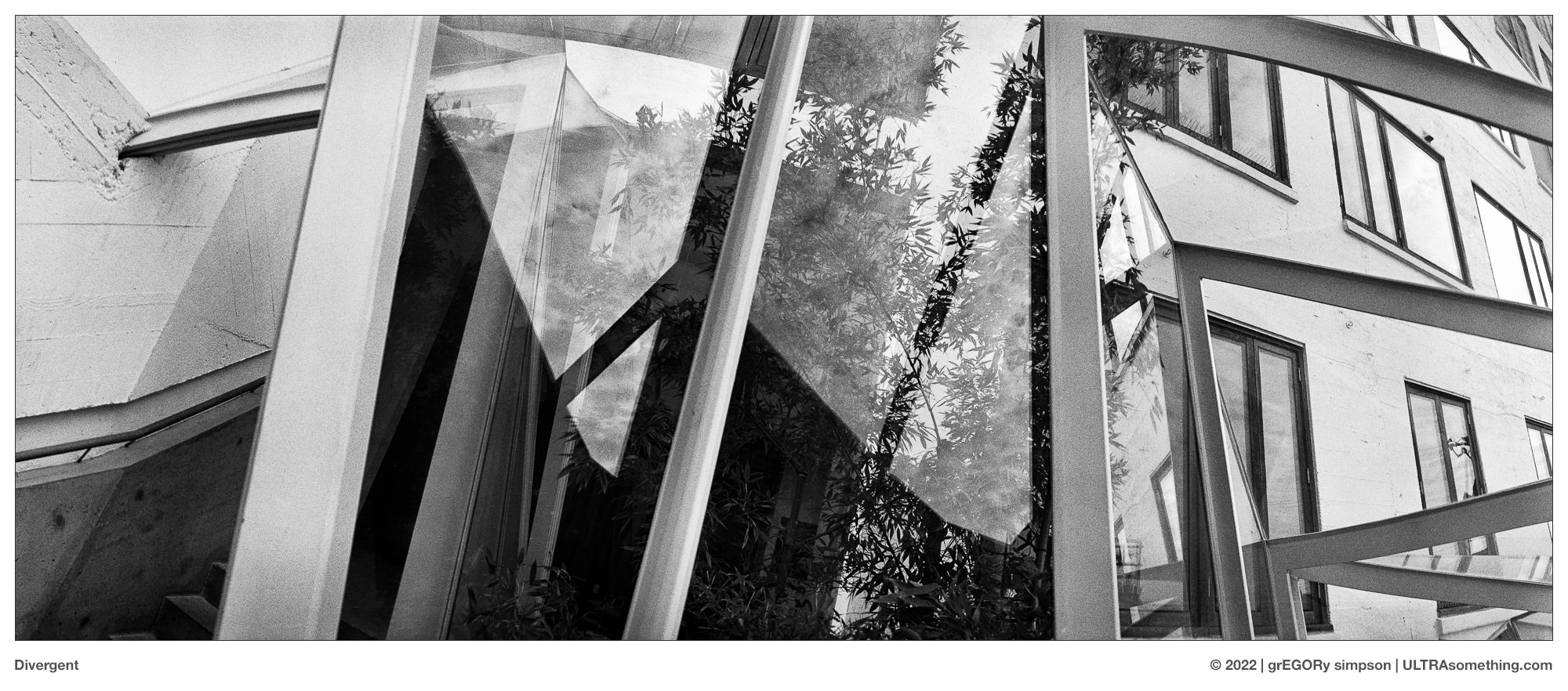

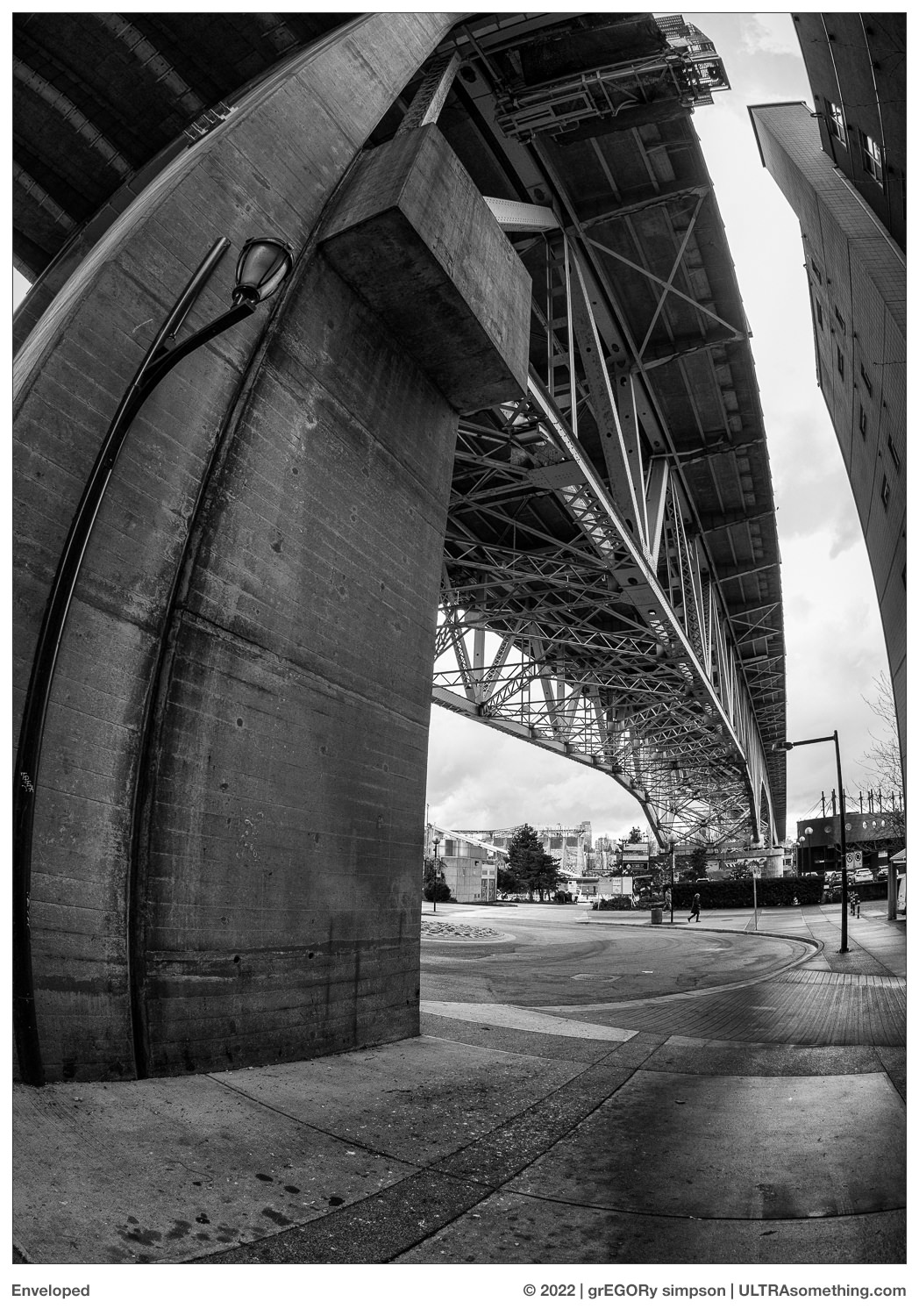

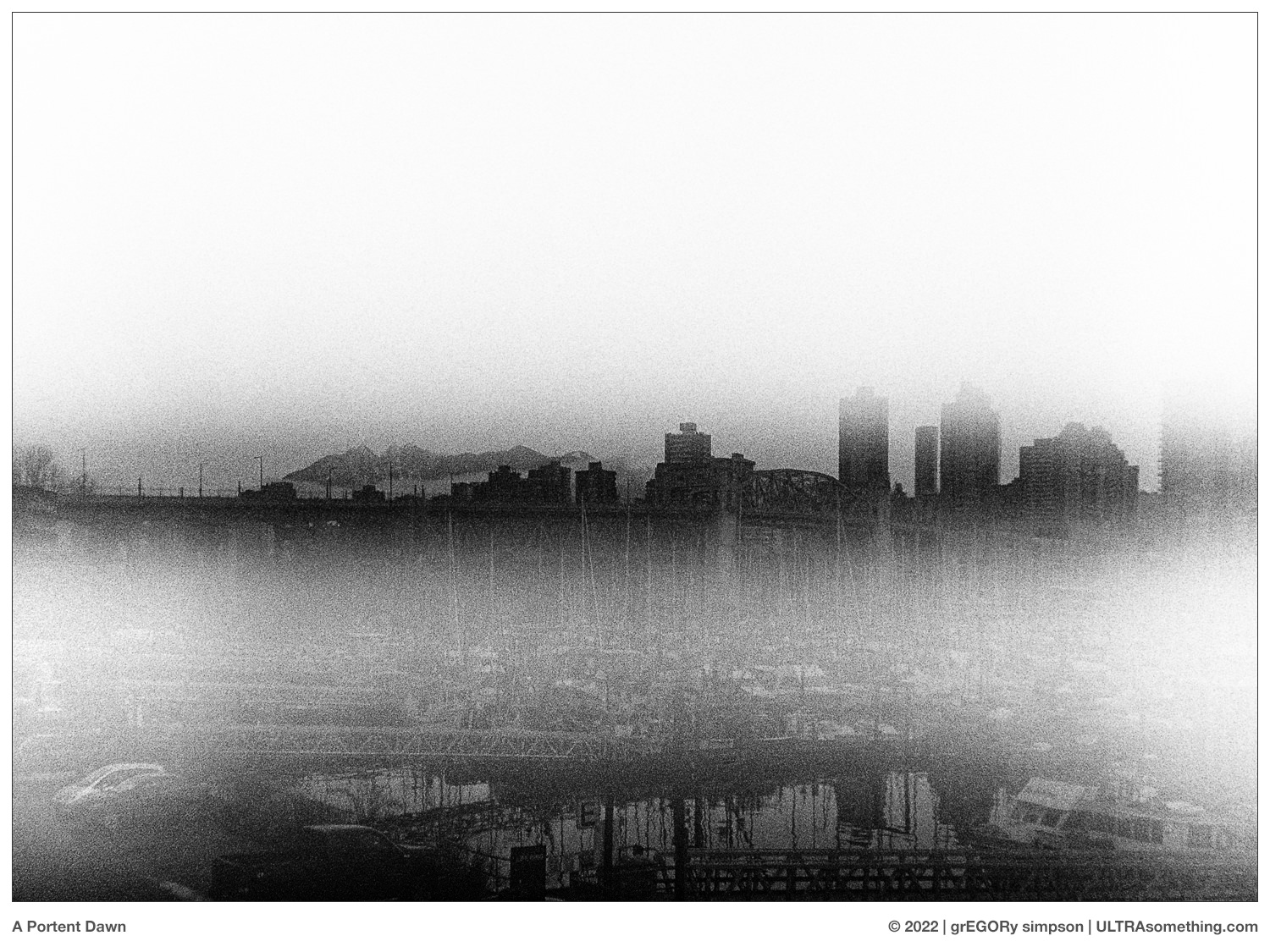

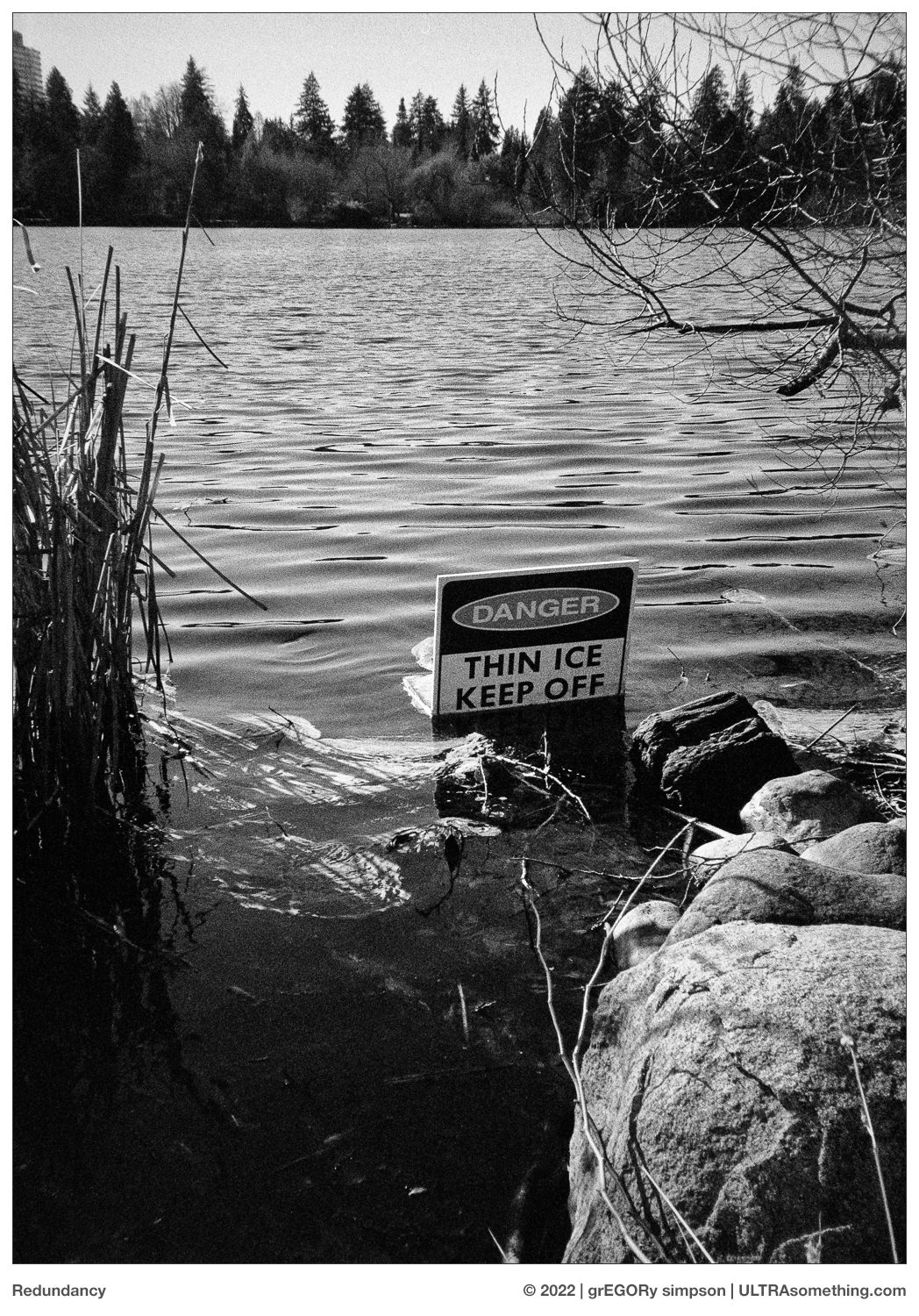

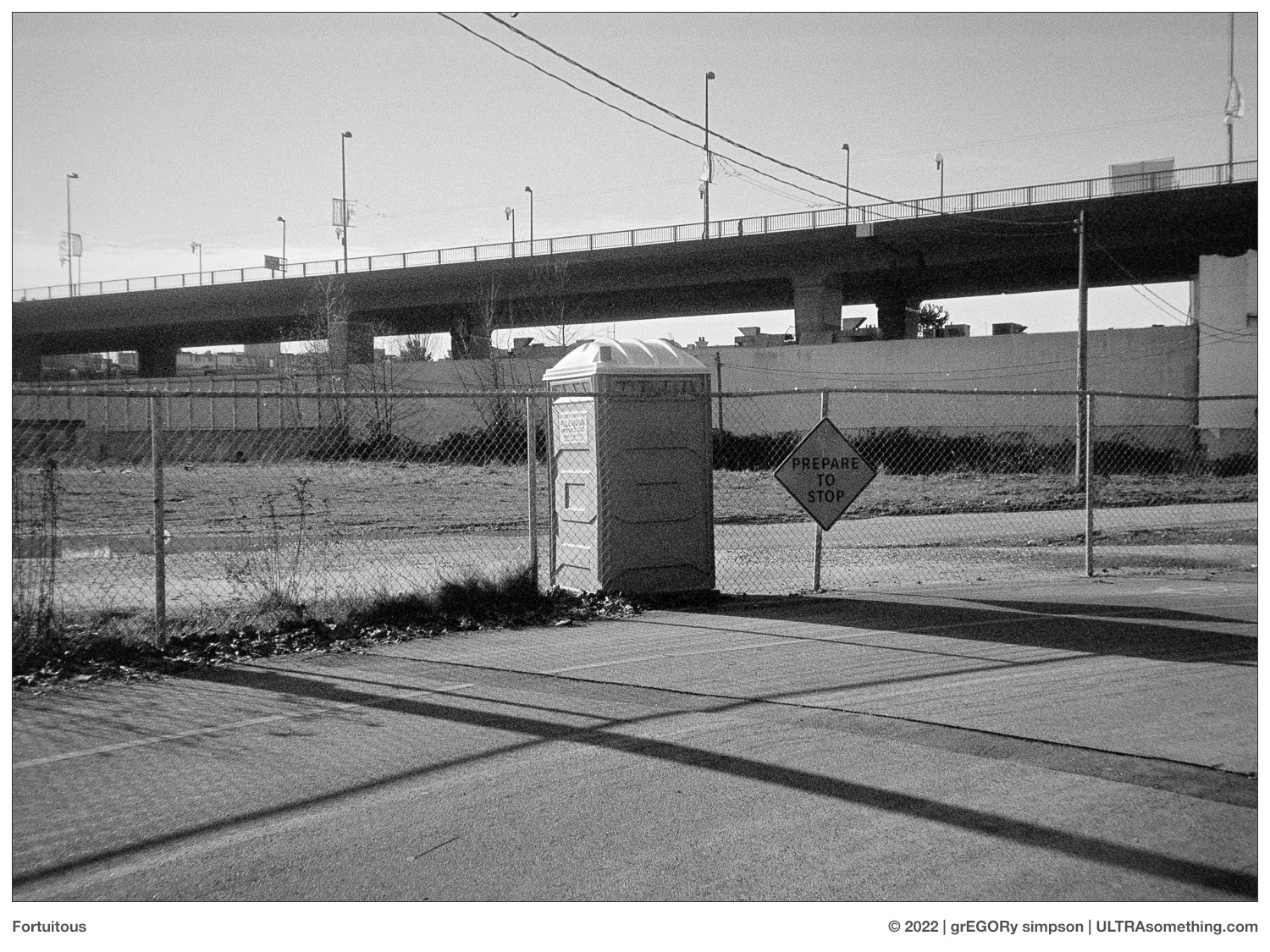

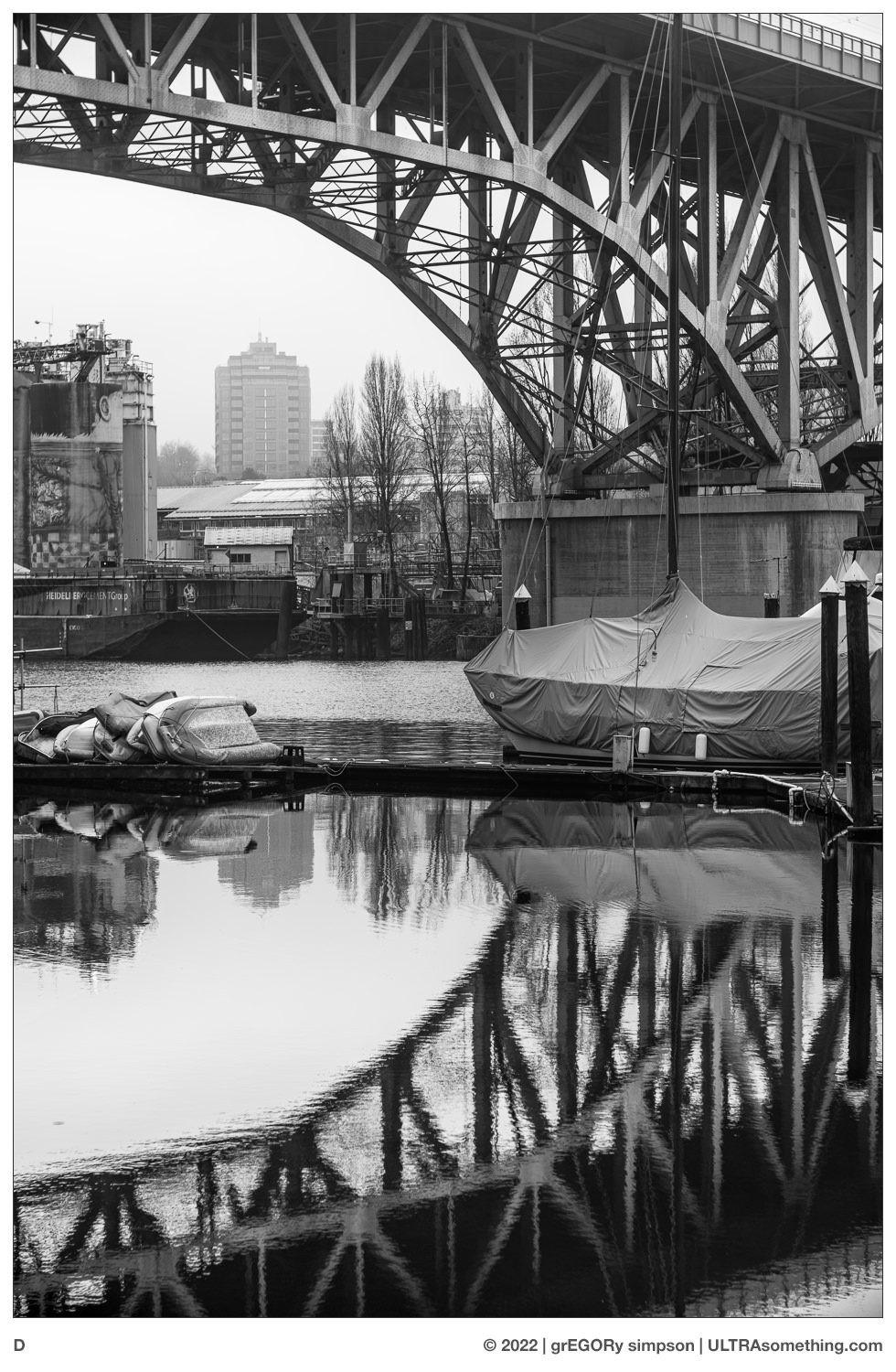

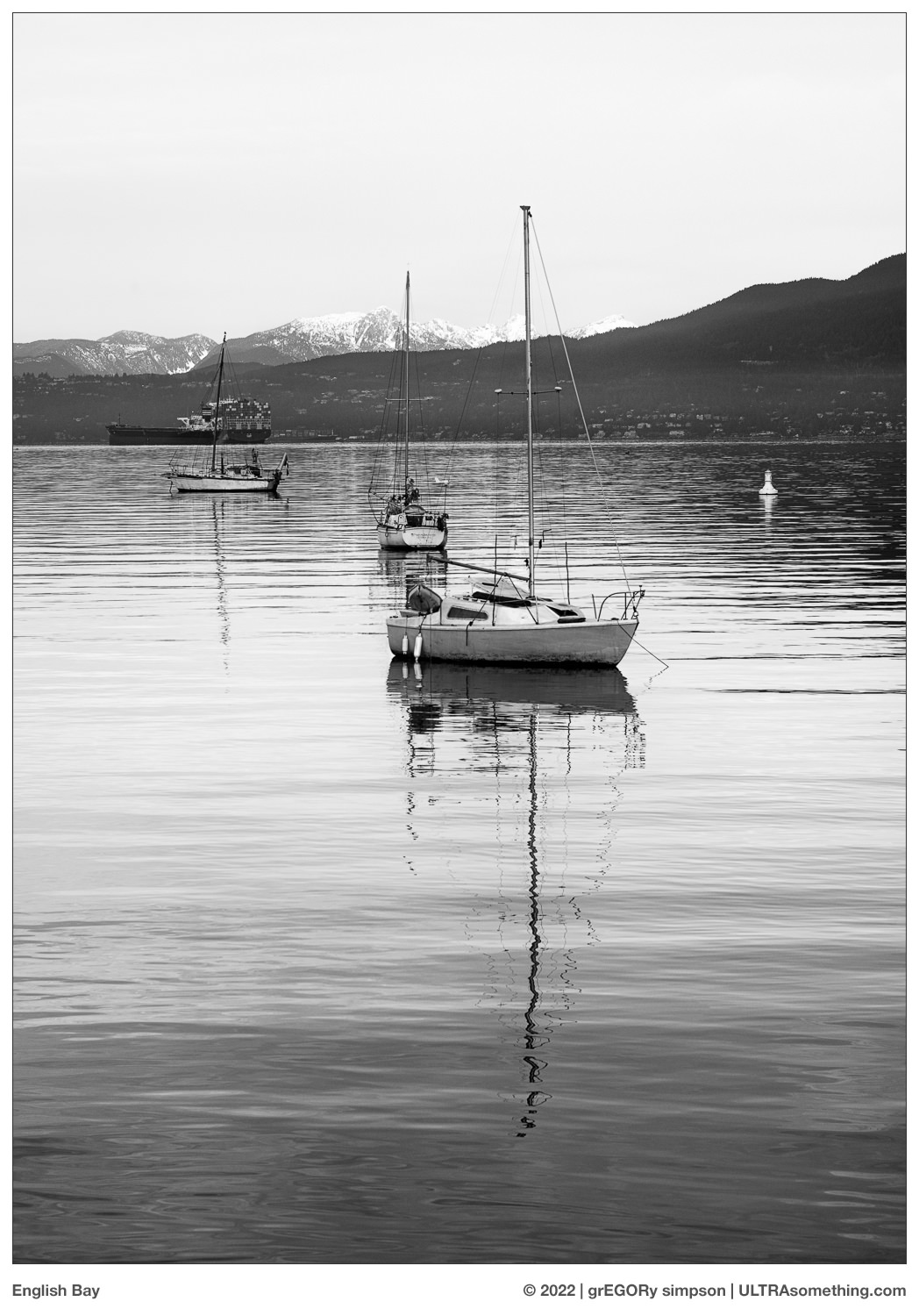

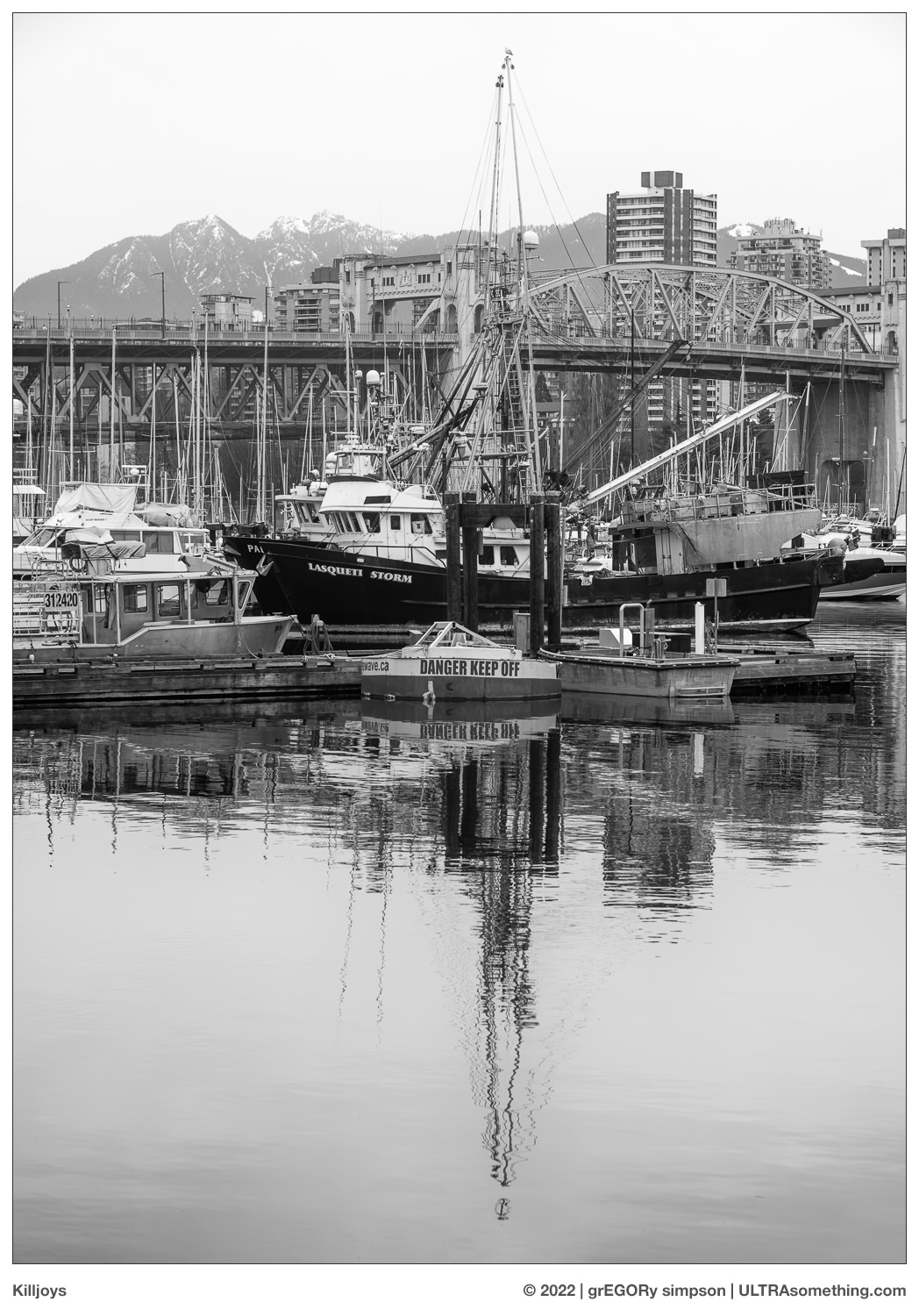

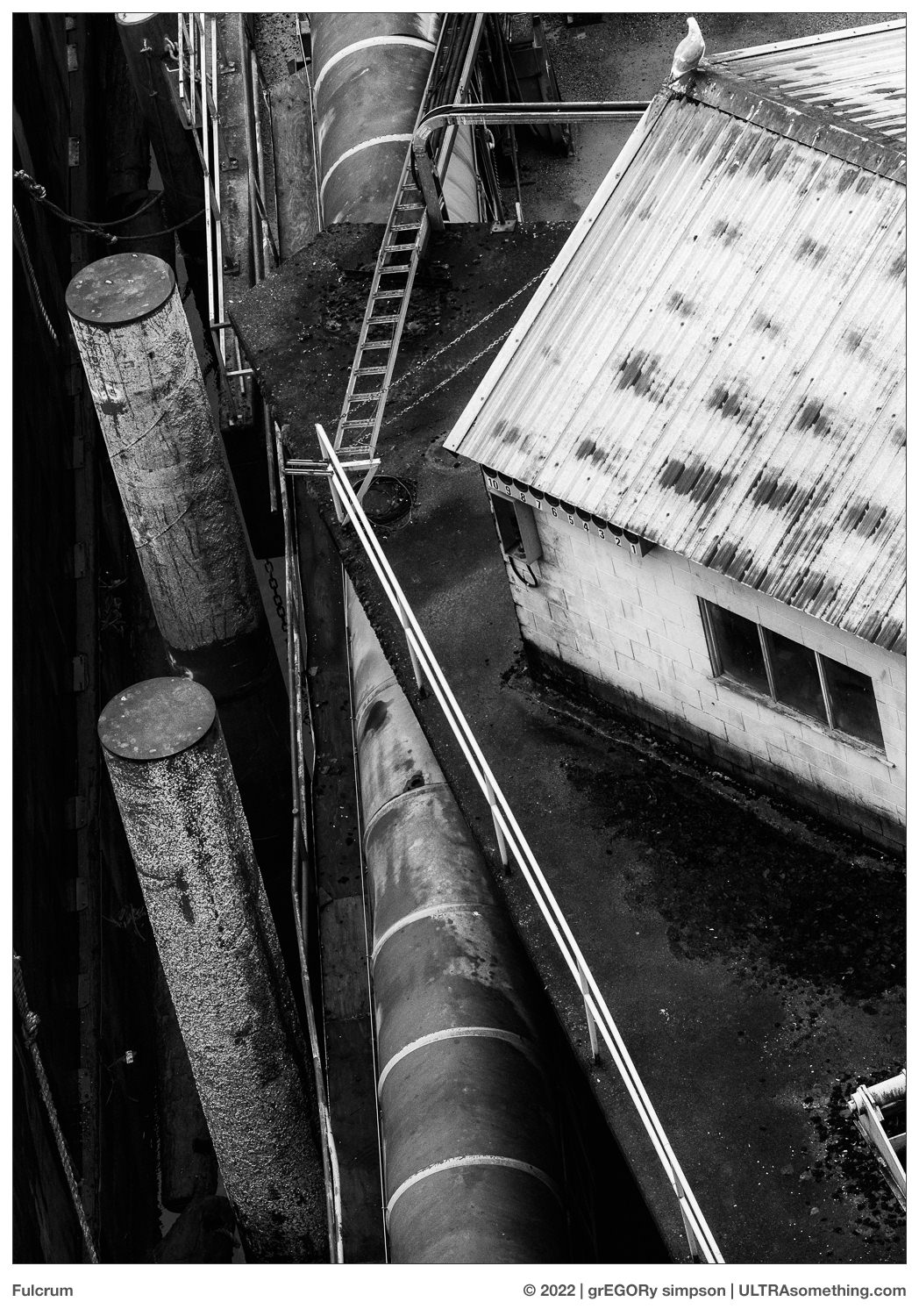

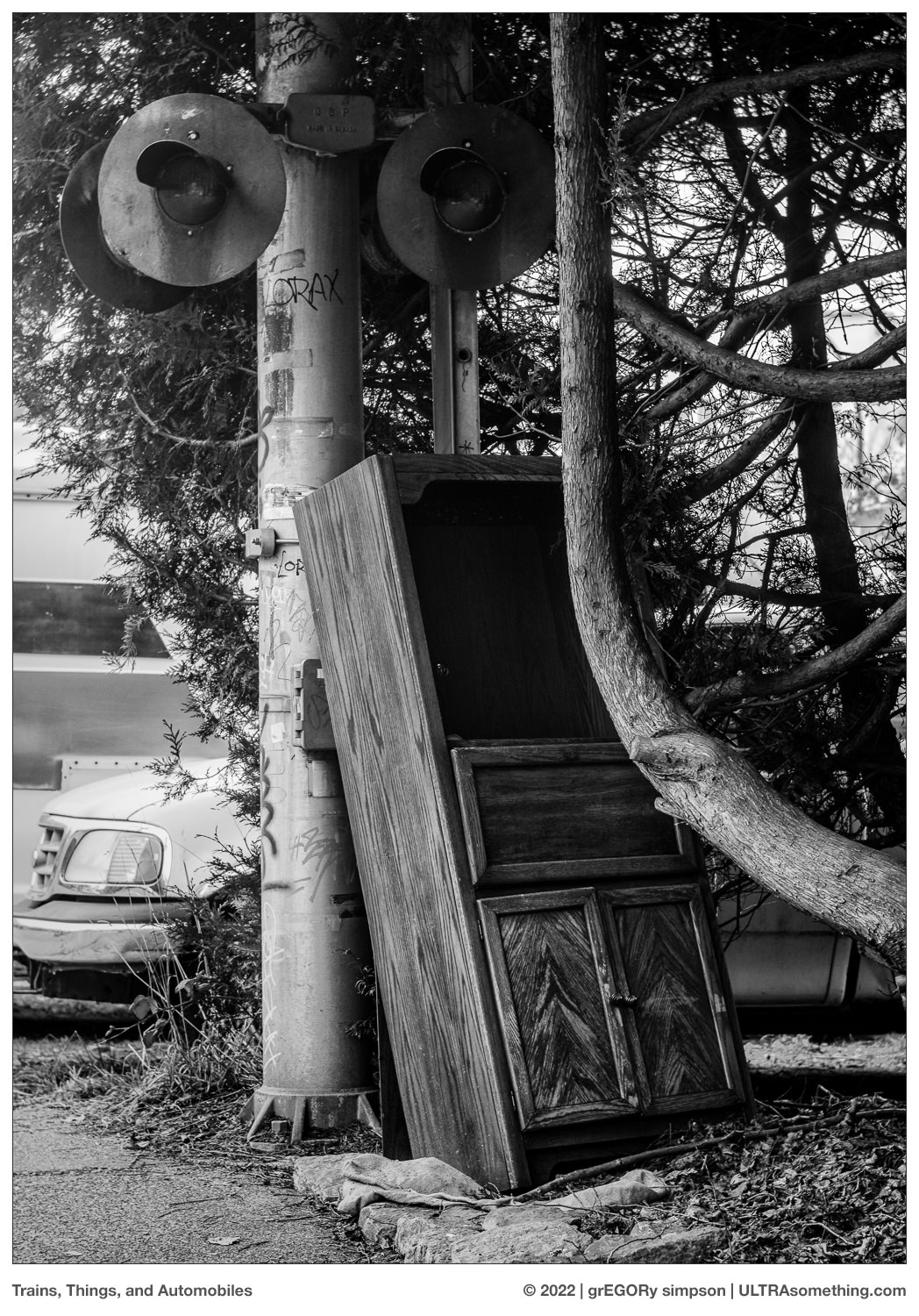

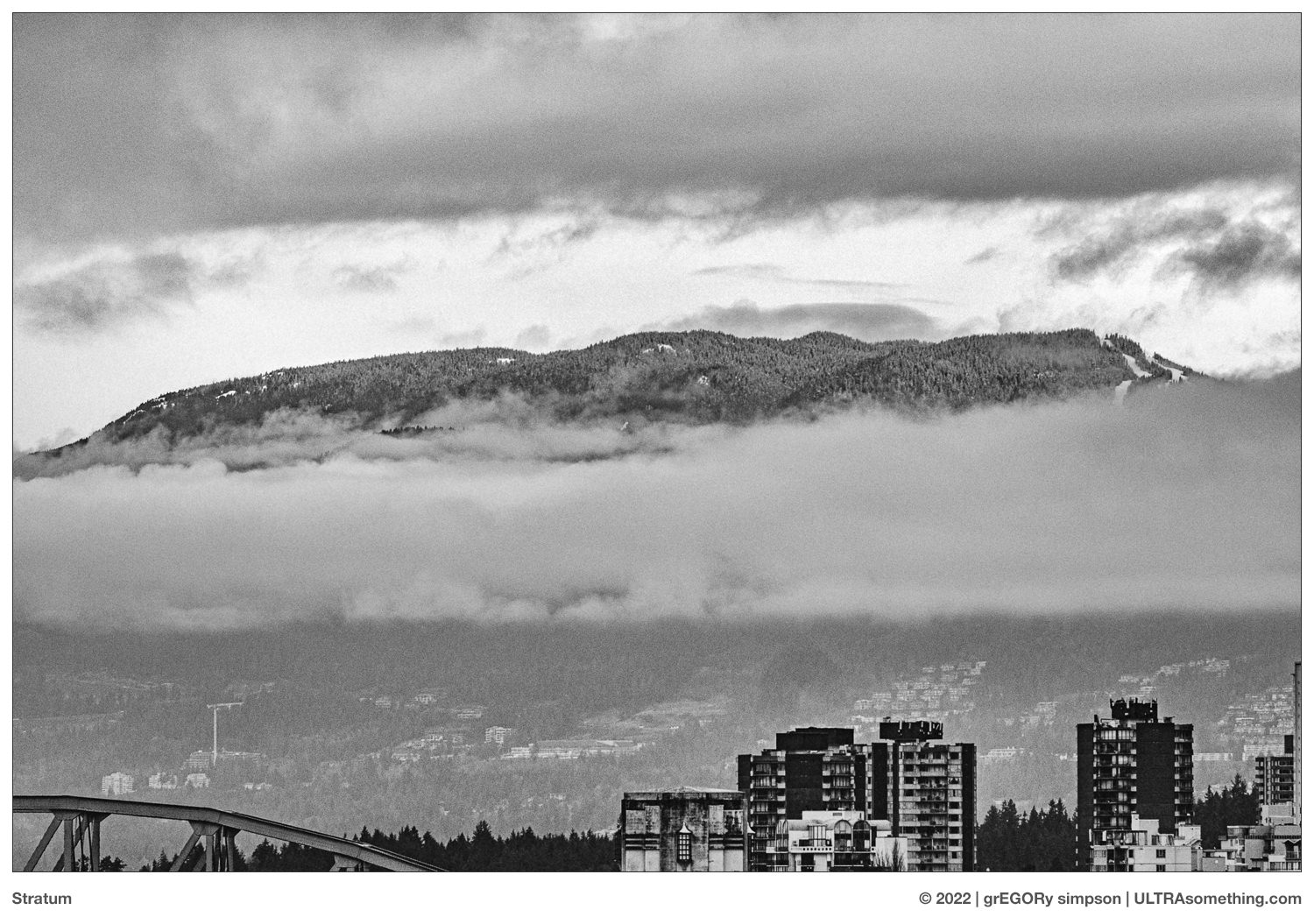

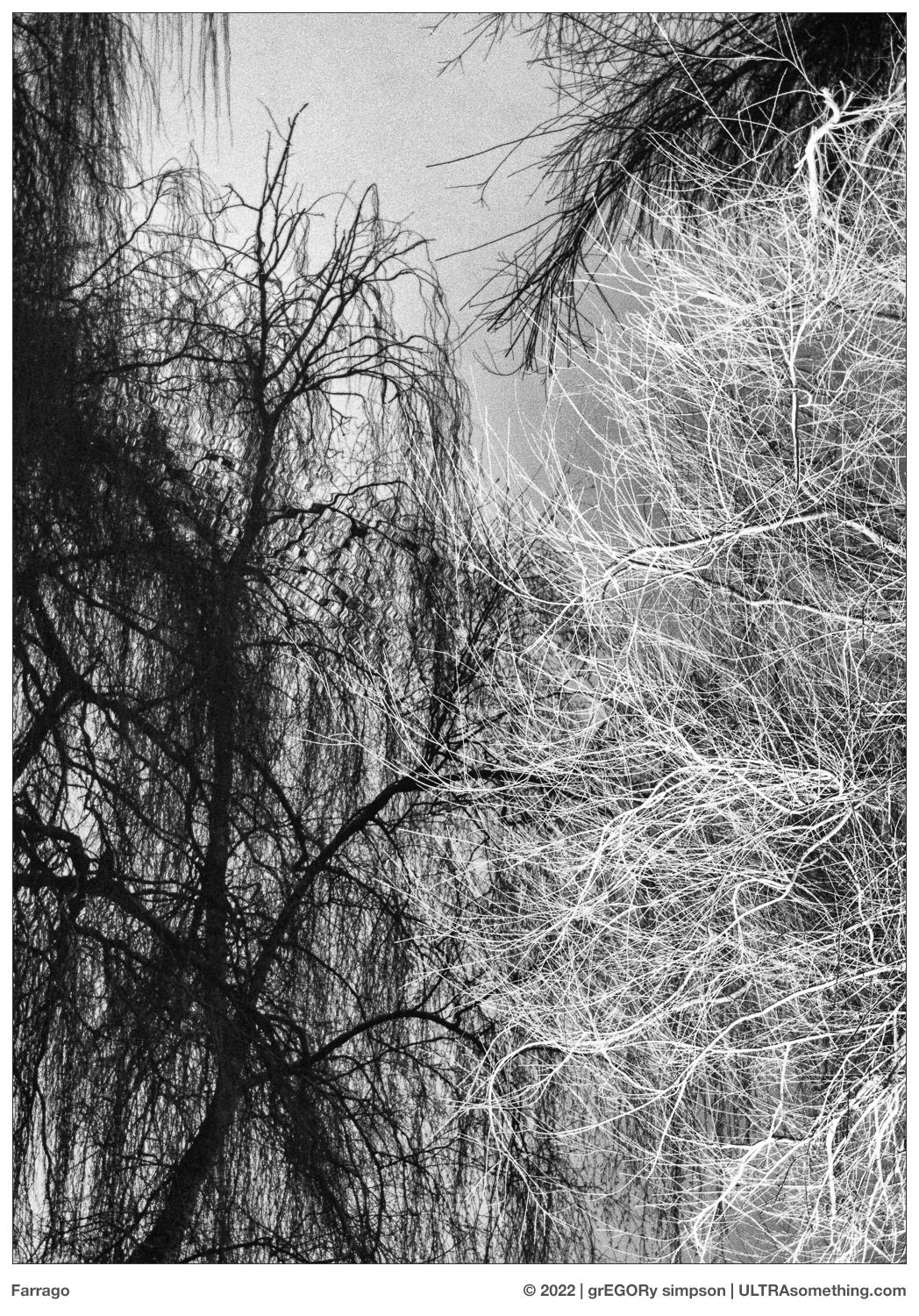

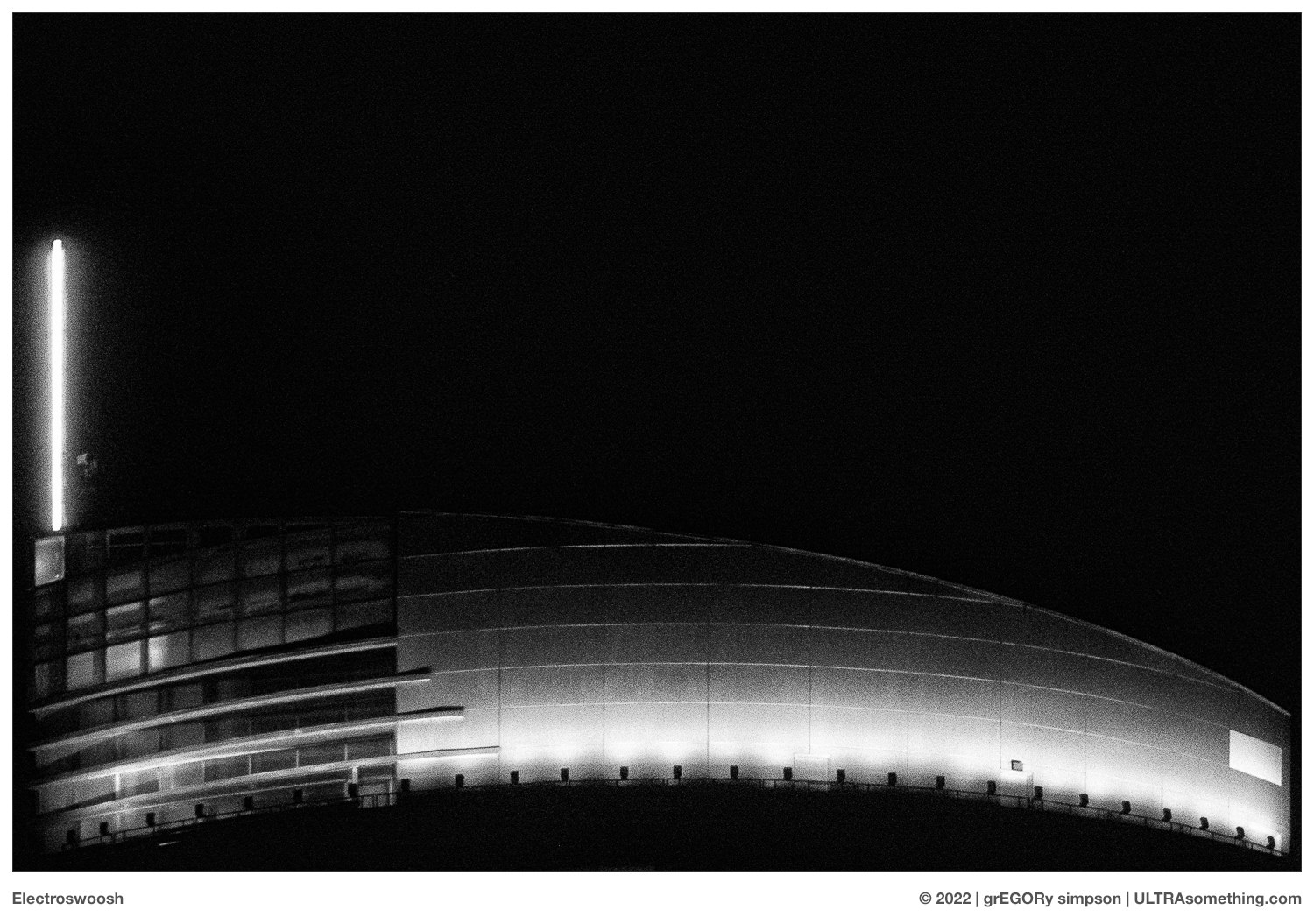

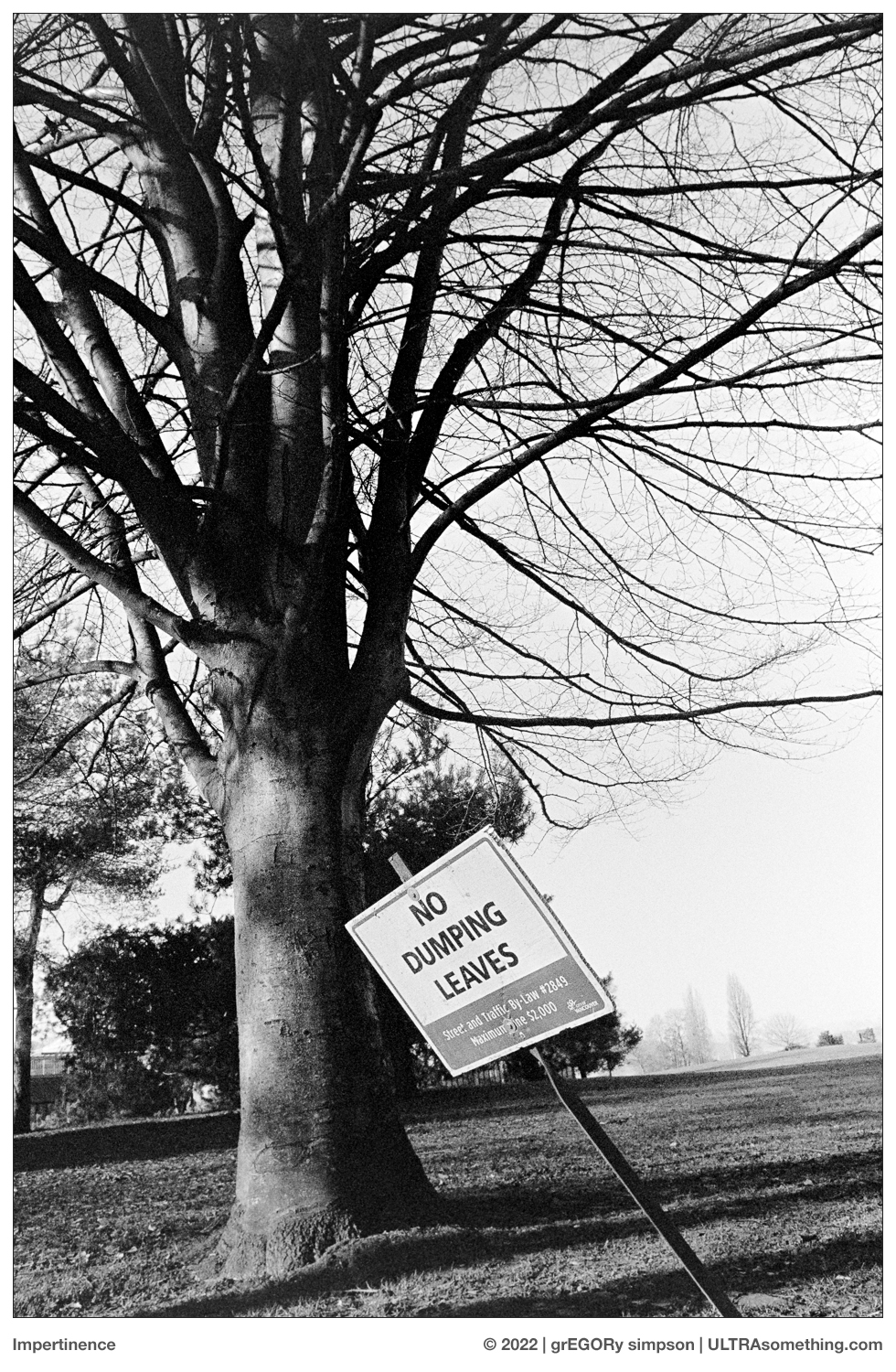

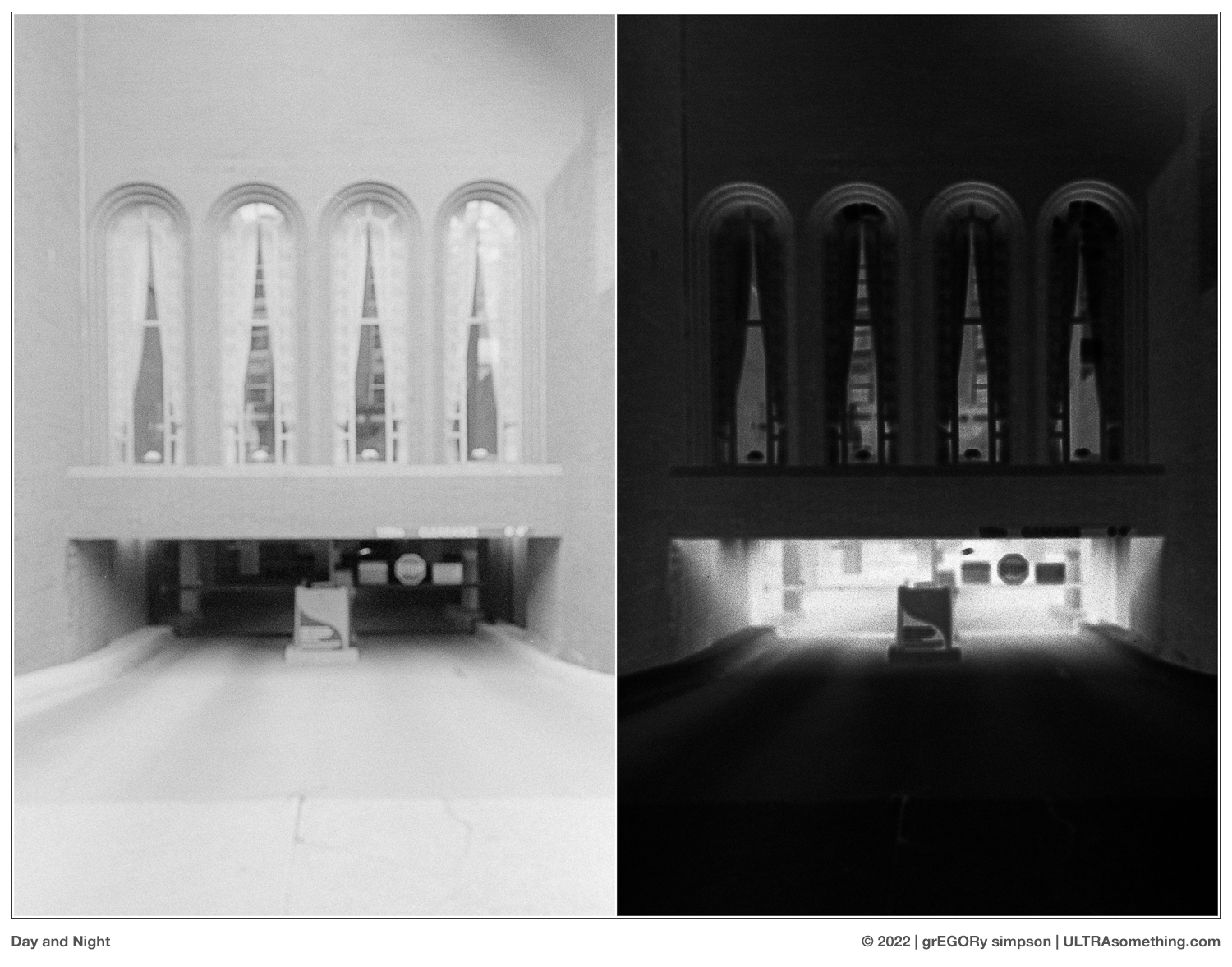

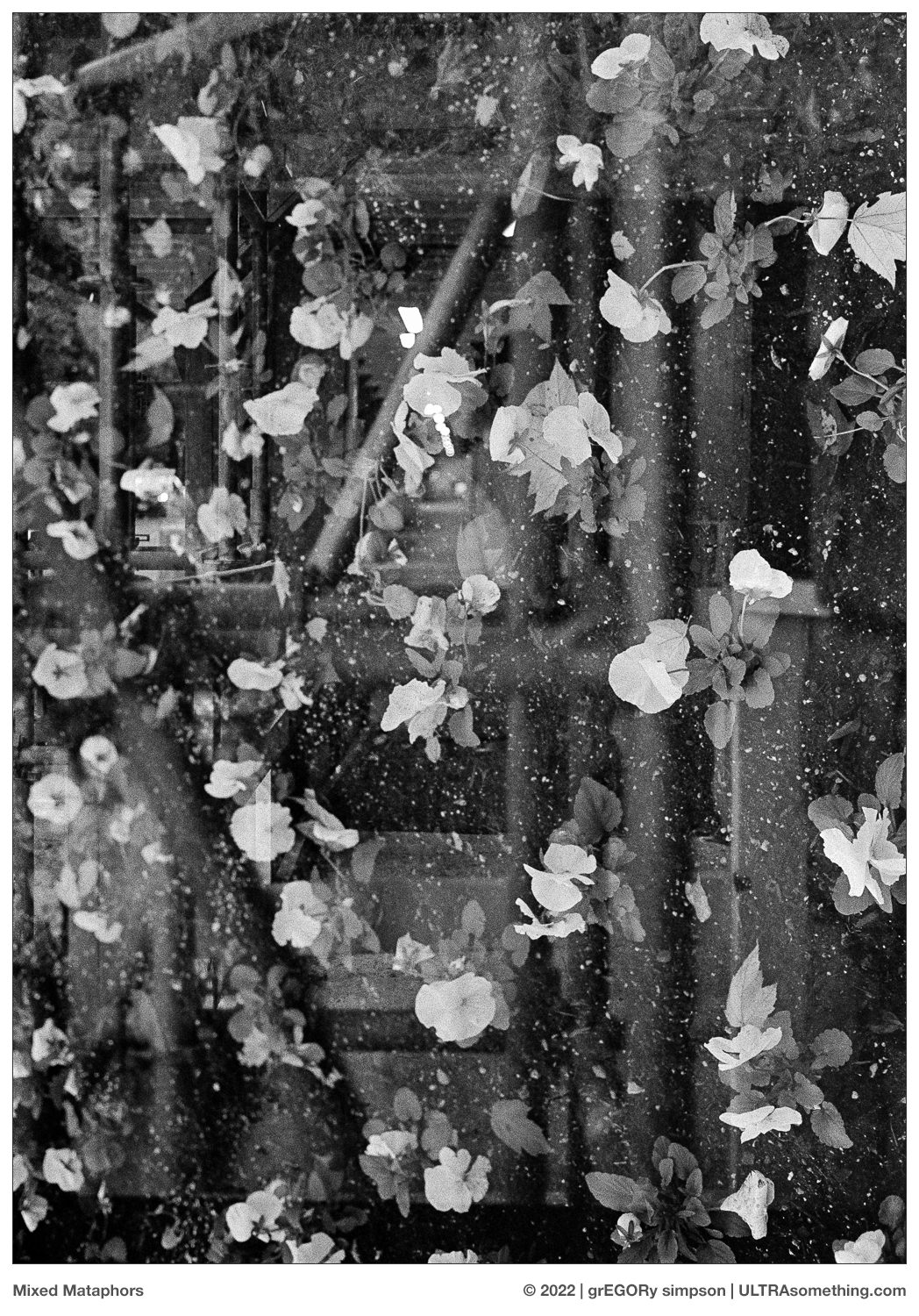

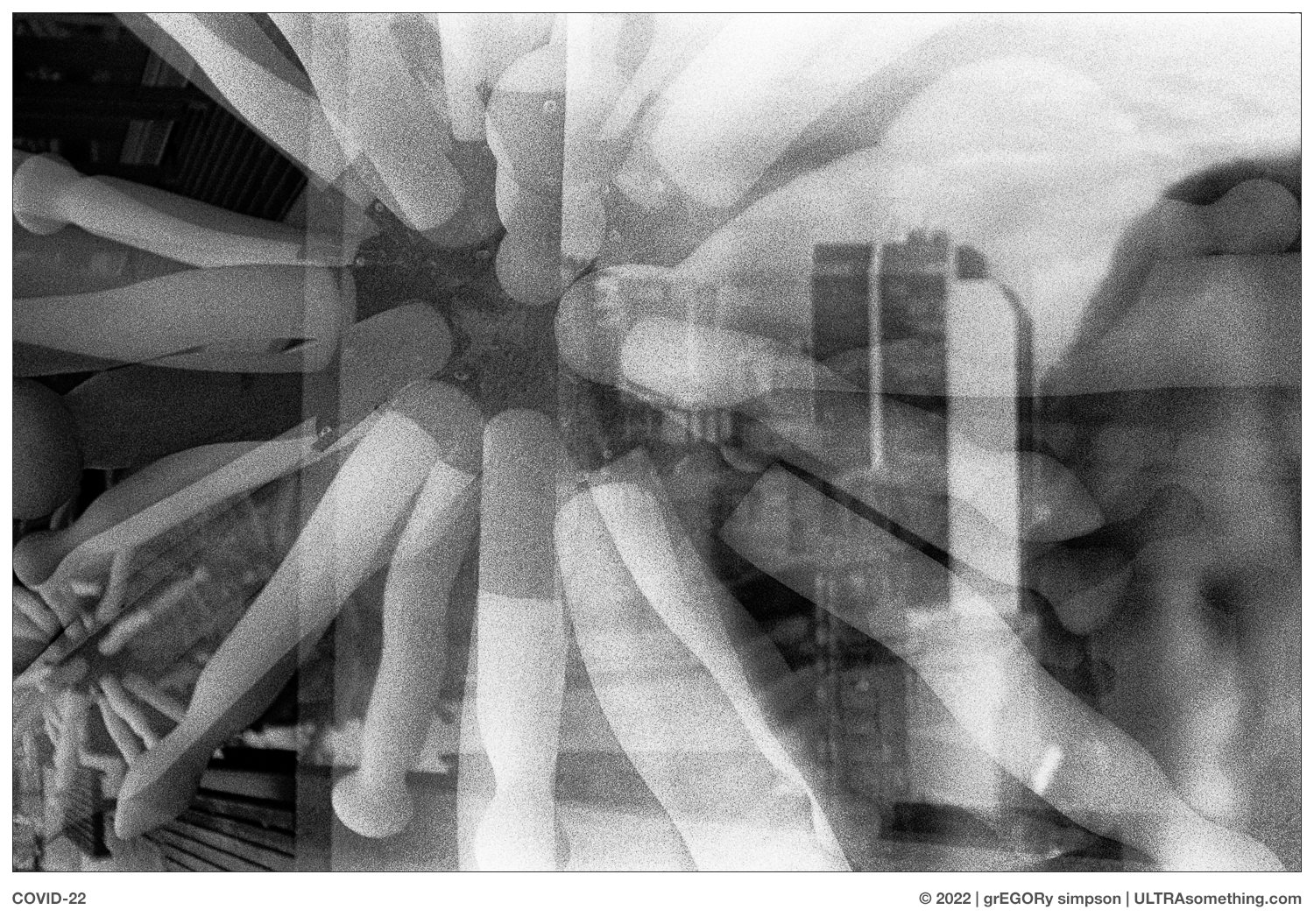

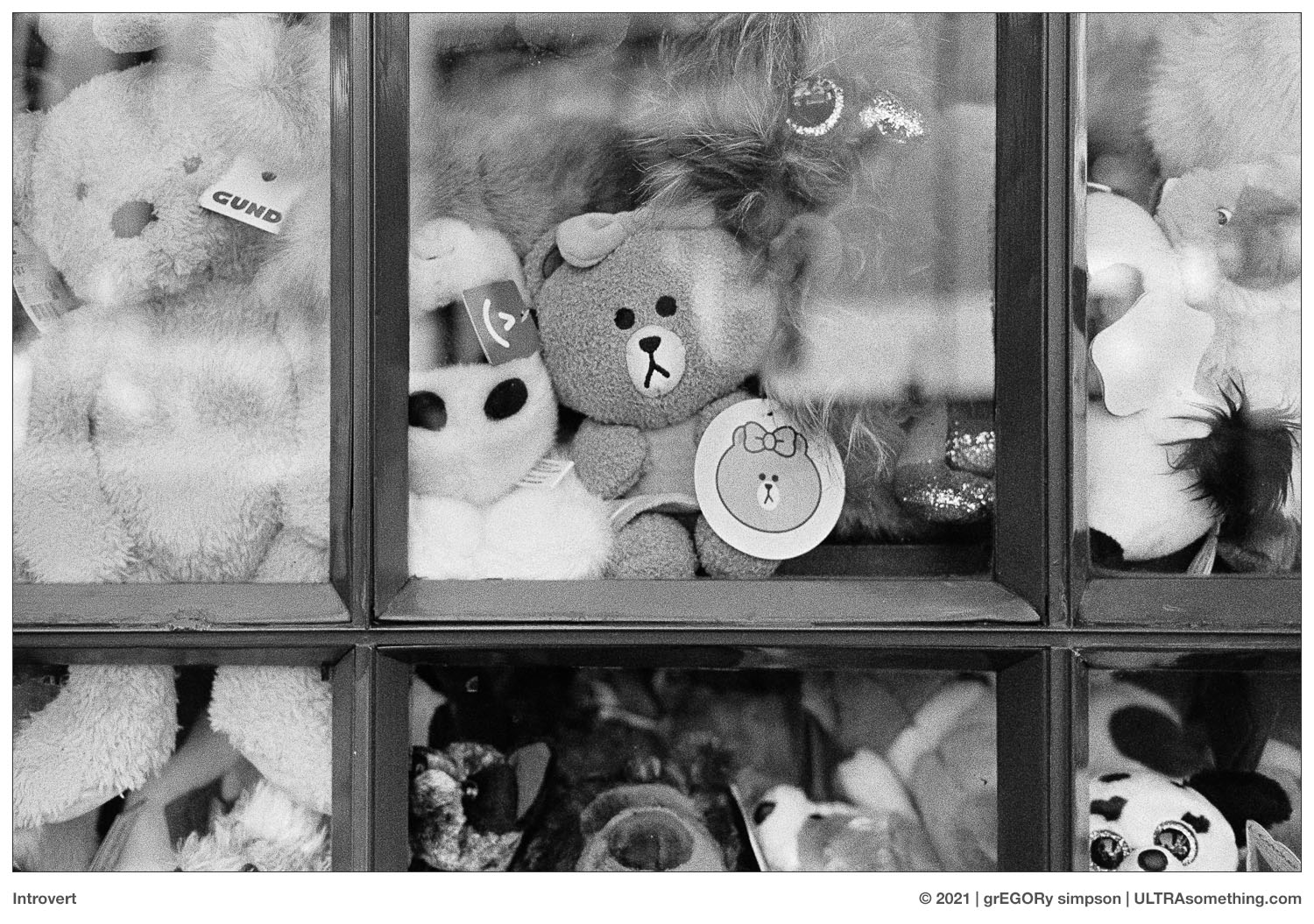

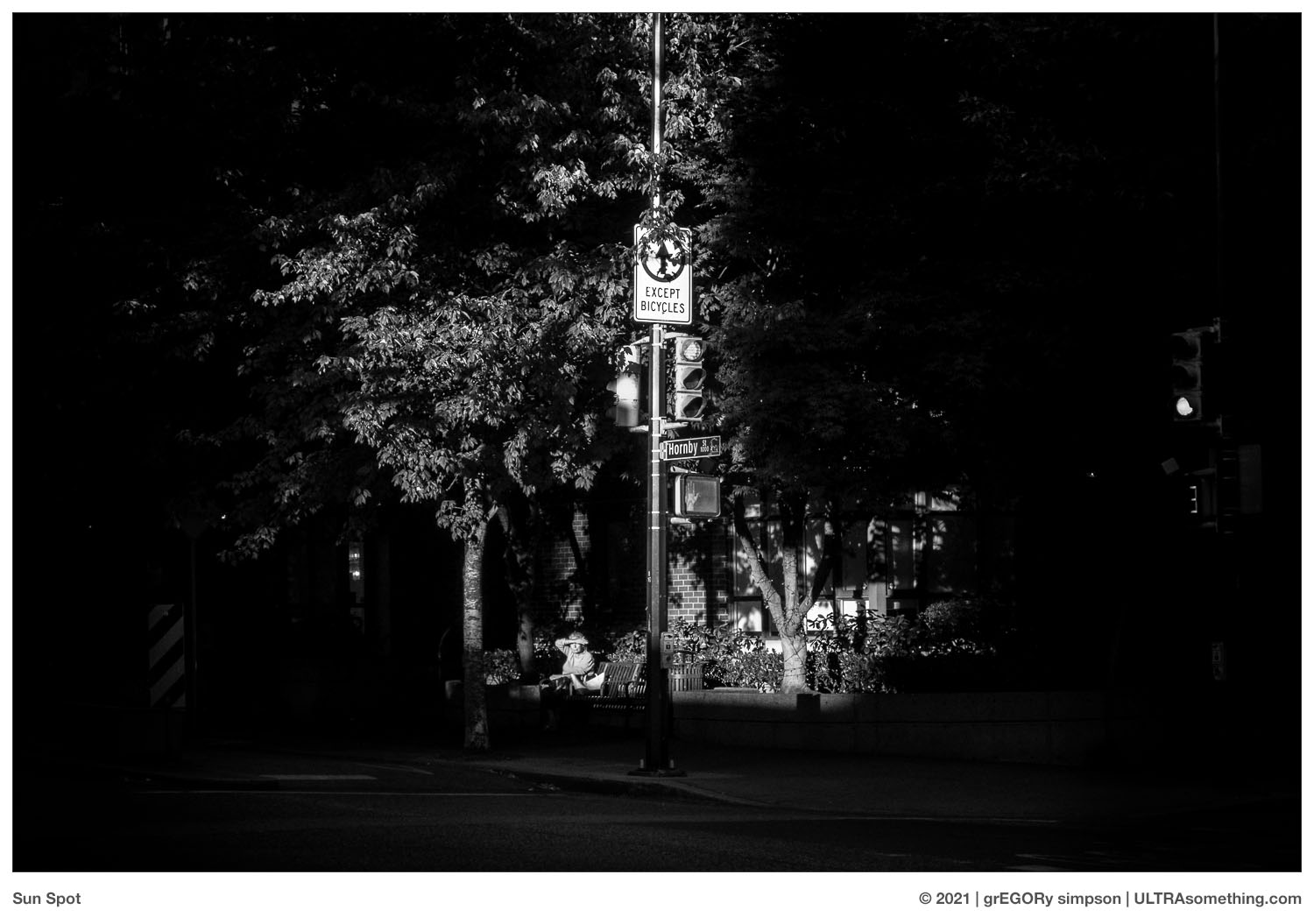

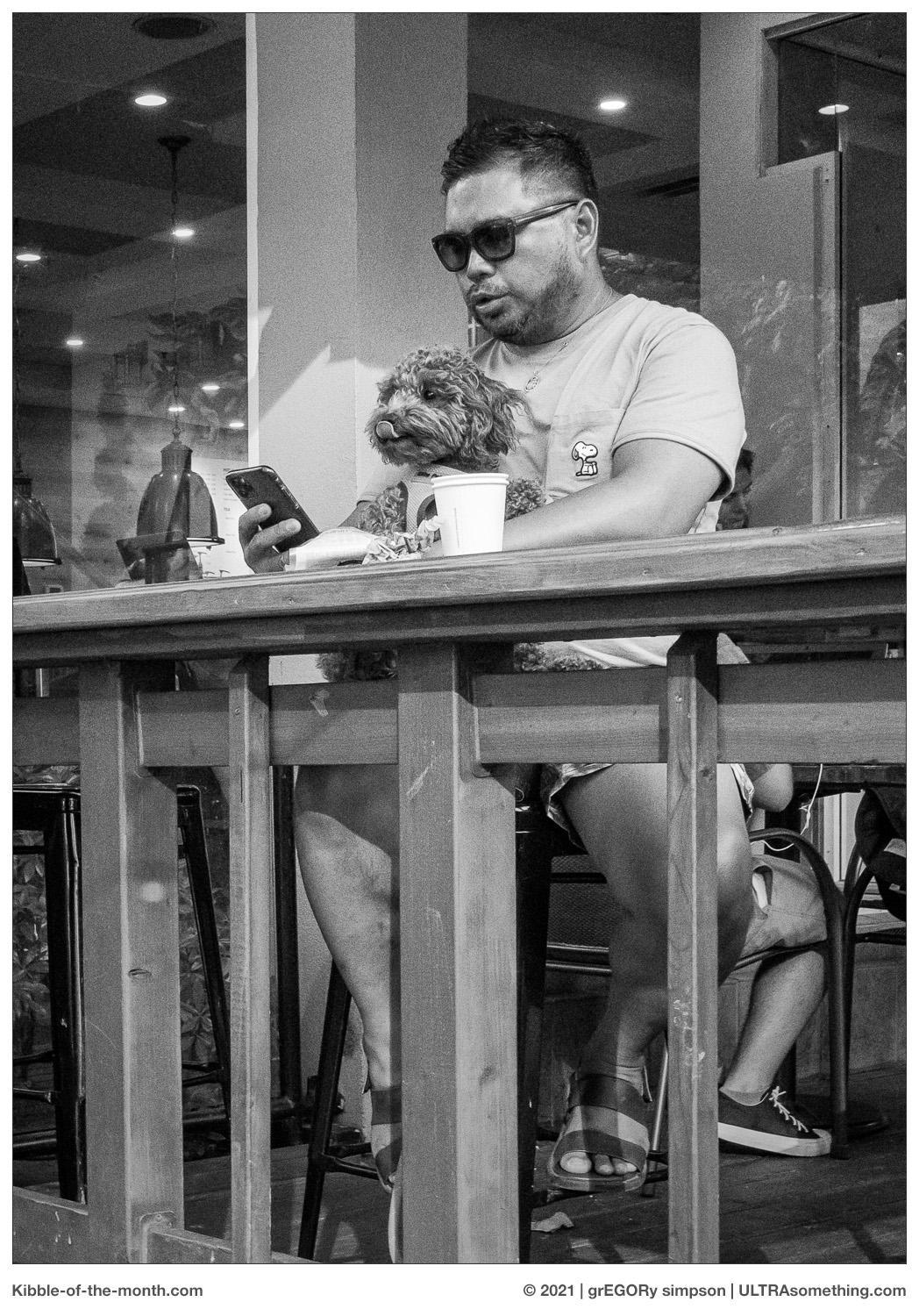

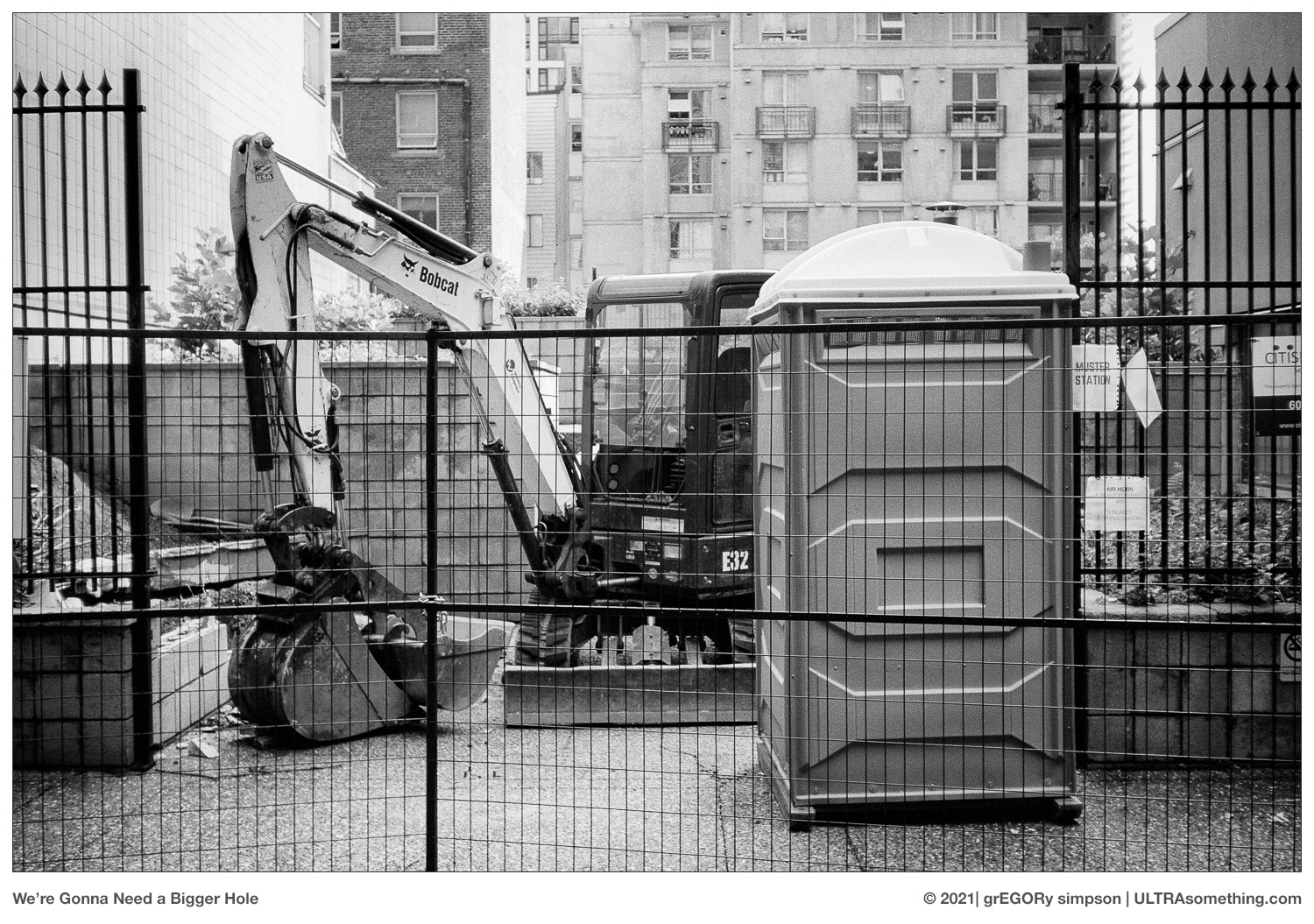

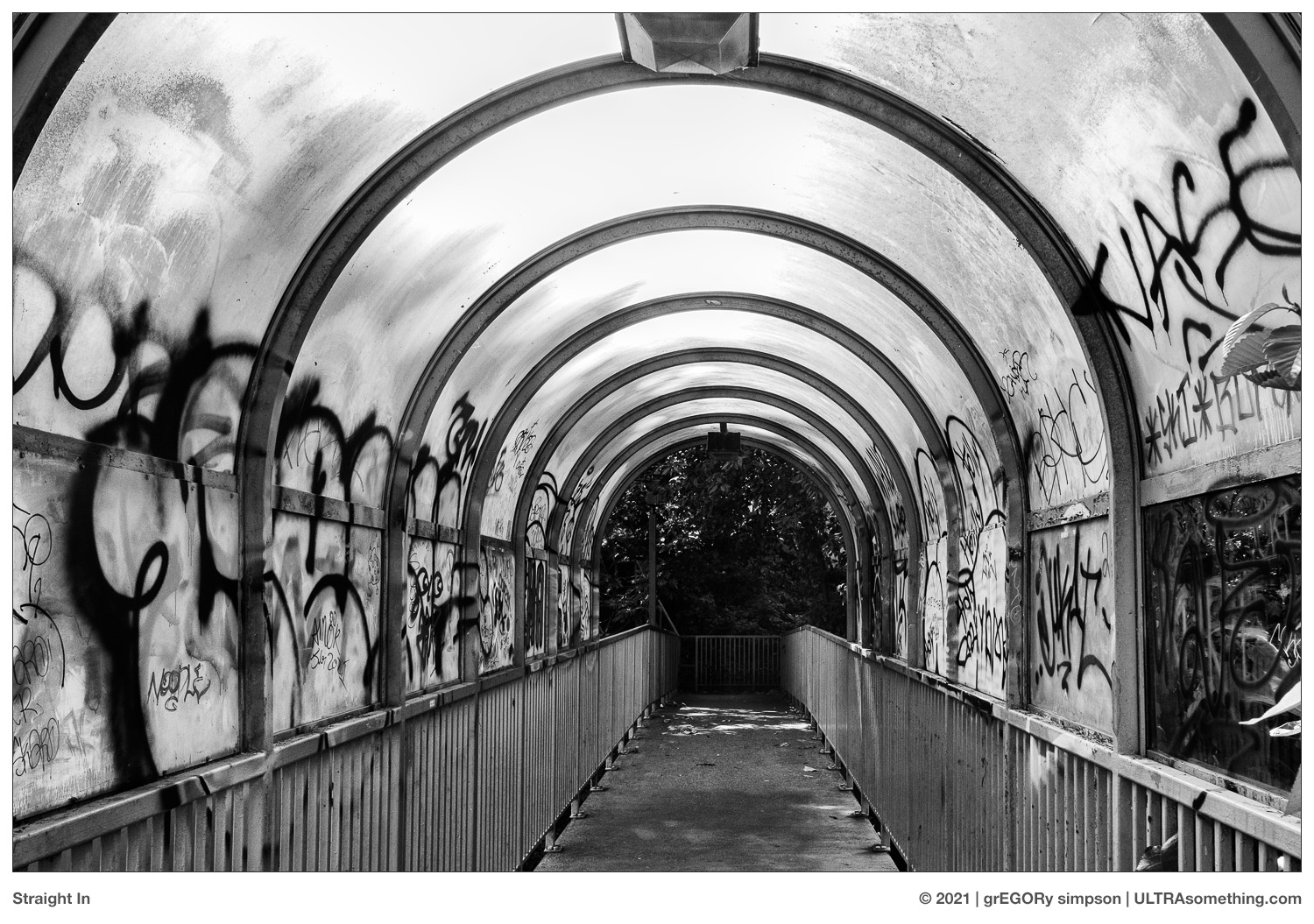

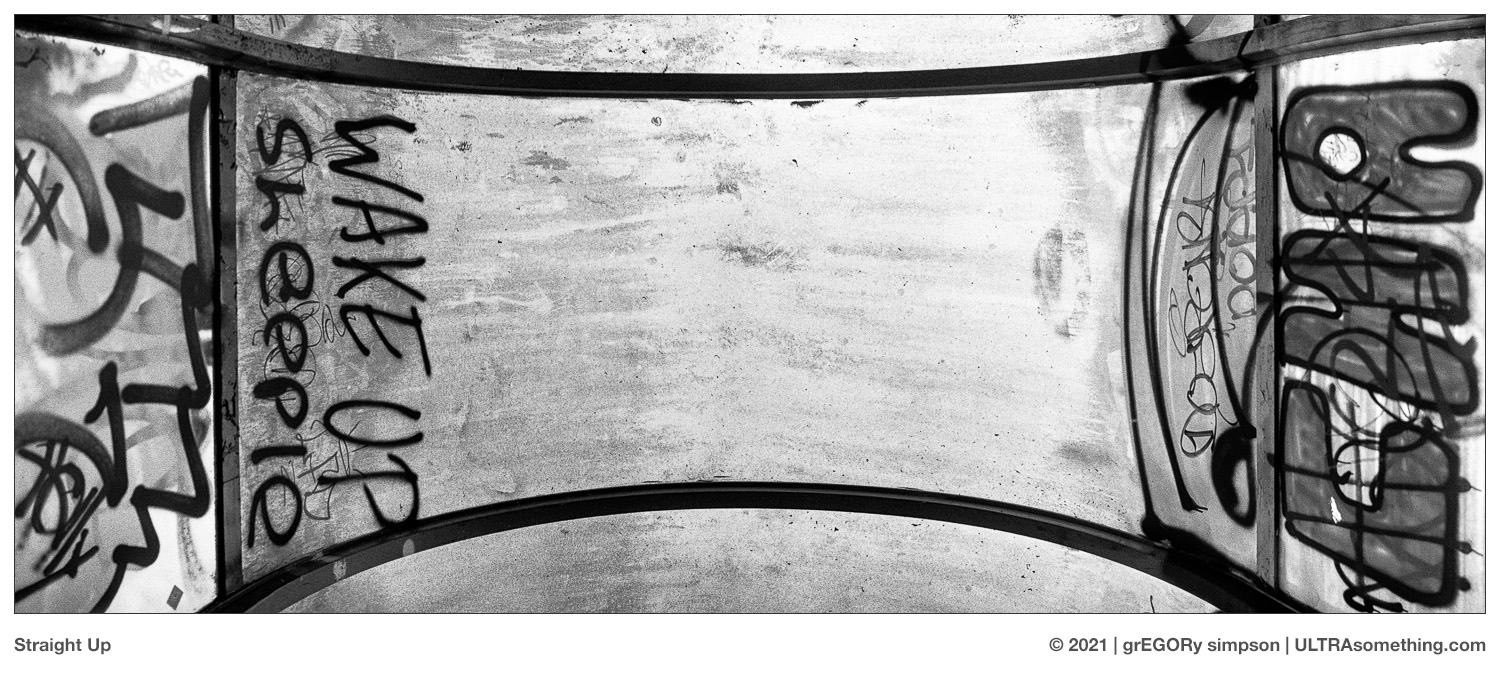

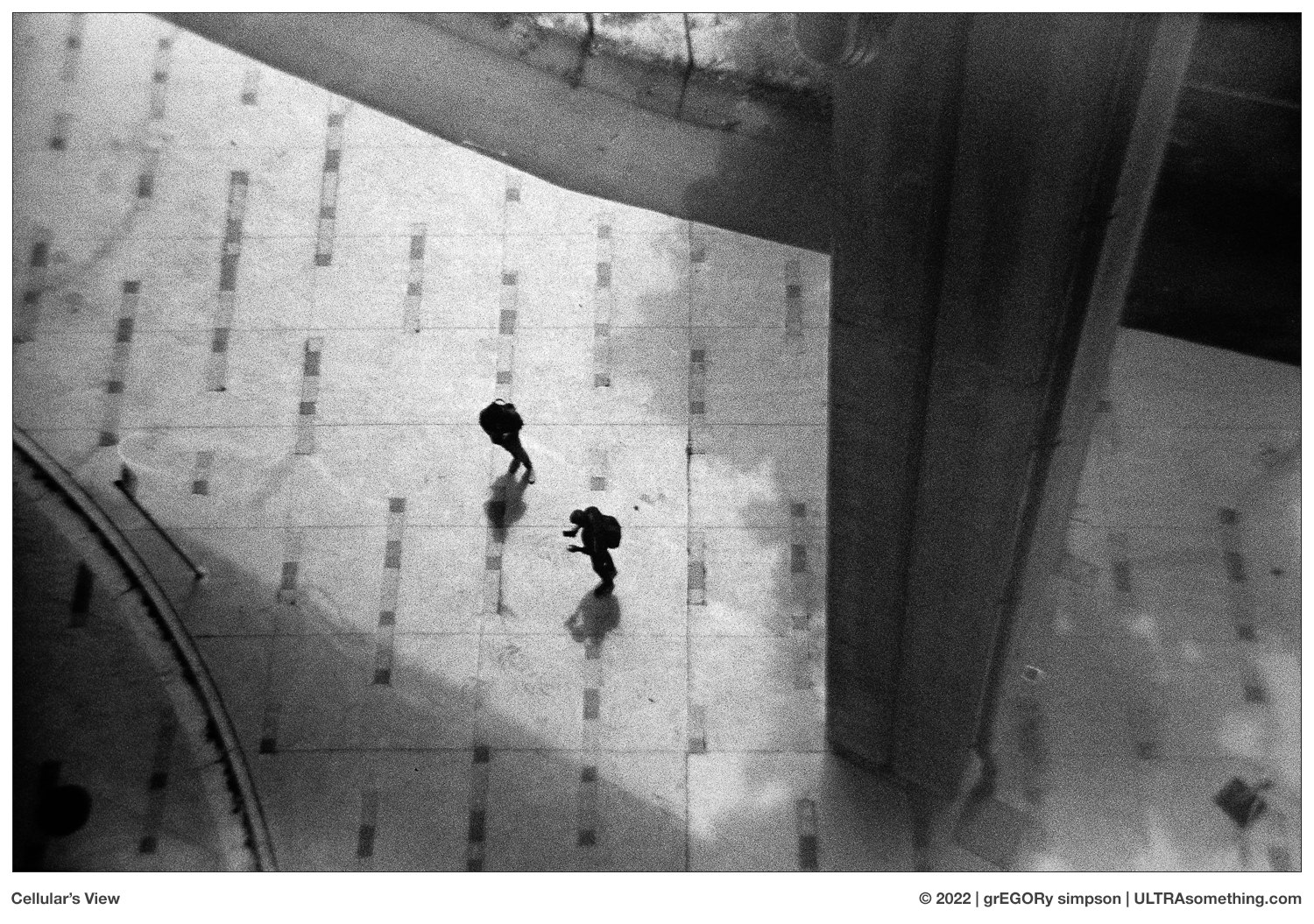

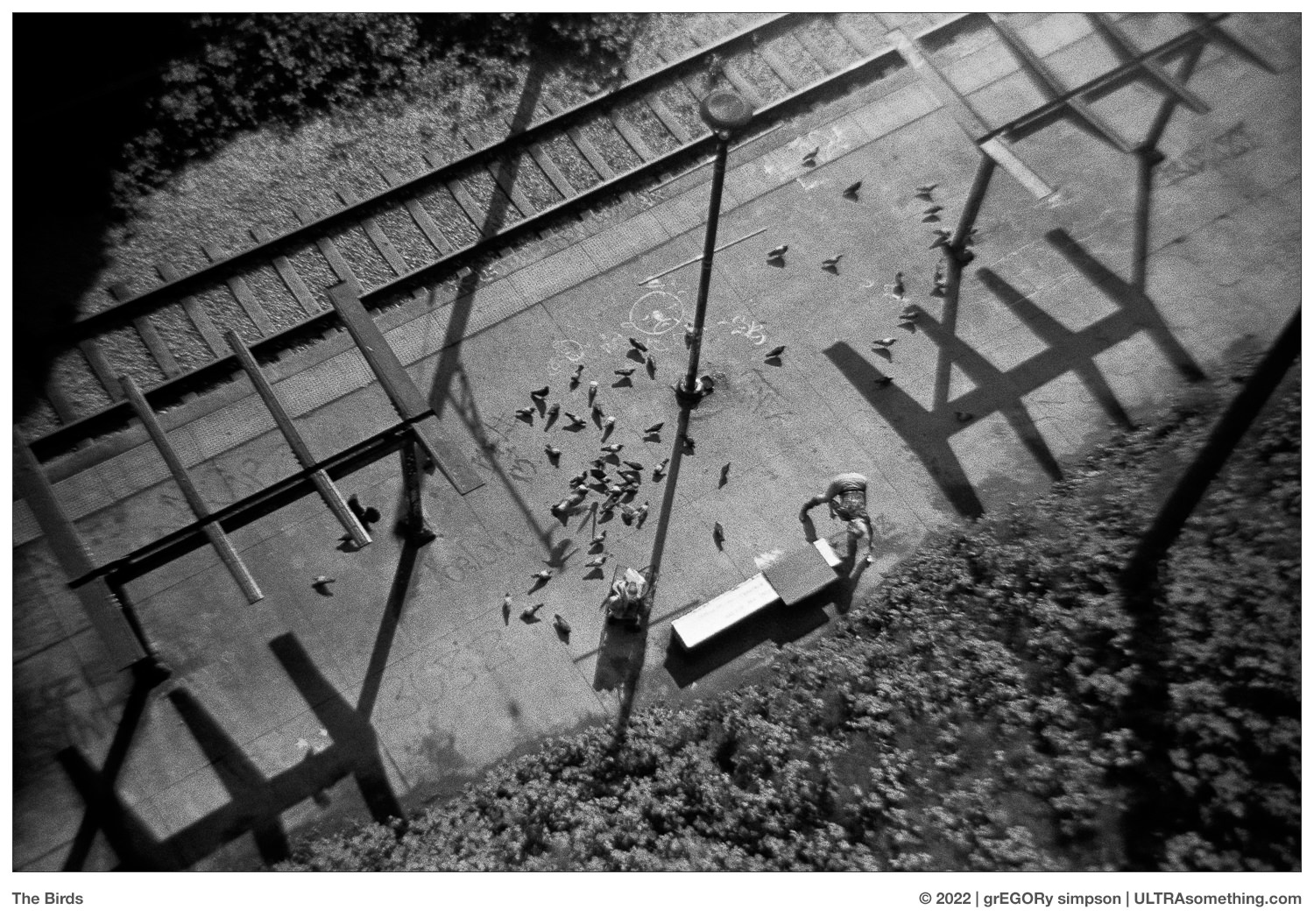

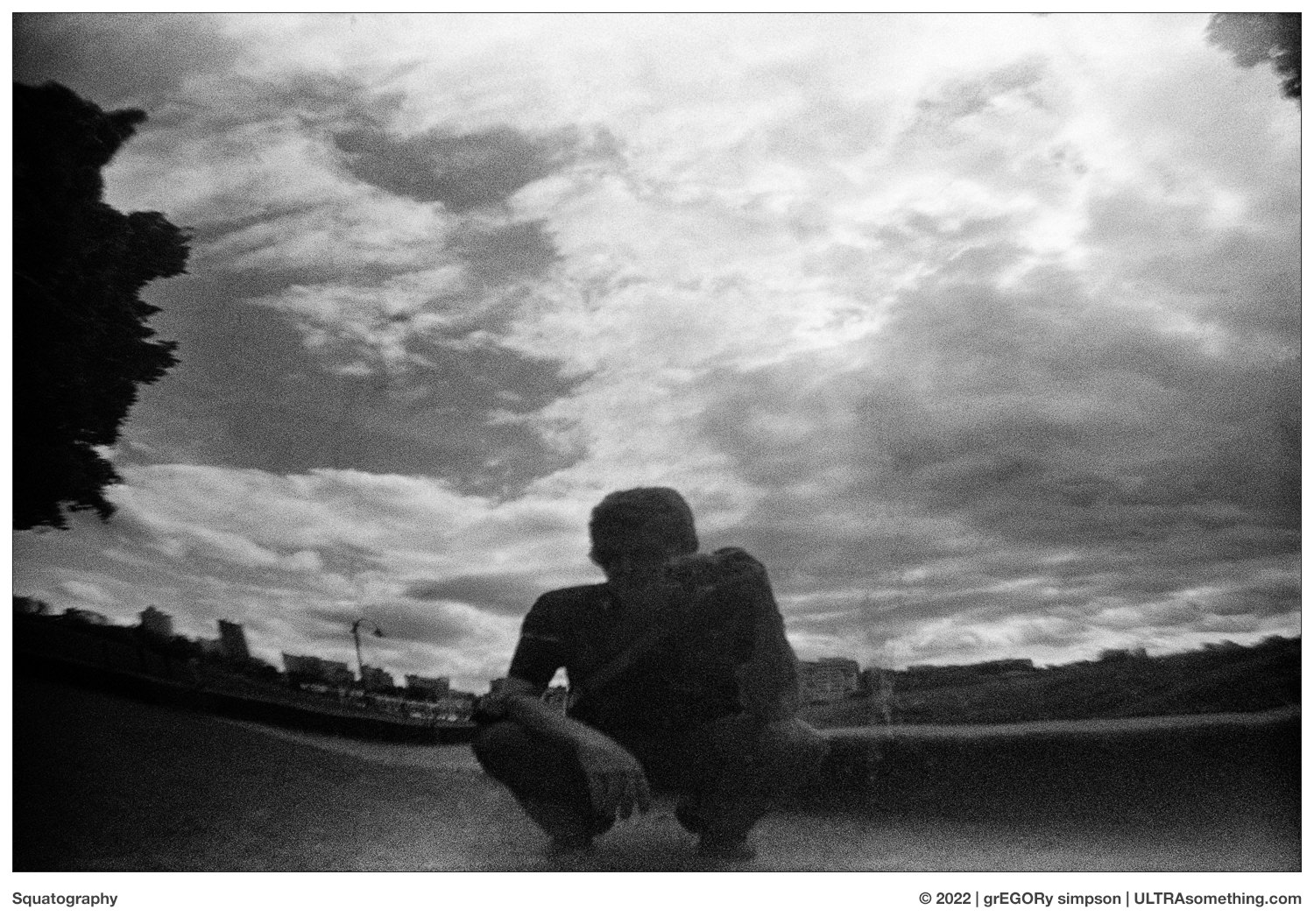

One of the main reasons I shoot half frame cameras (besides the fact I’m ‘cheap’), is their murky fidelity — somewhere between a photograph and a charcoal drawing. It’s a look I love, and one vaguely similar to that from the MVP, in spite of the fact it’s not a half-frame camera. However — not content with just a little smudge — the MVP pushes the murk factor into overdrive. It’s as if you took a half frame image; loaded the film on the developing reel without bothering to use a dark bag; processed it in exhausted chemicals; framed it behind a frosted sheet of plastic; and coated the corners with Canola Oil.

I’ll admit, given the curious inclusion of a glass lens, I expected a modicum of fidelity. But once I extracted the first reel from the development tank, those expectations got slapped down by the big clammy hand of reality. The images this camera produces are an abomination — and this is exactly why I love it.

Unfortunately (from a remuneration standpoint) my tastes are “utterly inconsistent with modern visual tastes.” So any camera that delivers such taste (in spades, no less) falls squarely into the trilogy’s definition of folly. Characterful images are contrary to the inclinations of the literally-minded, sharpness-obsessed influencers of today. Most folks want their camera to define the subject, not interpret it. They want to see details, not suggestions. Perhaps, if this was the late 19th century and the dawn of pictorialism, it would be a camera of desire — much like the Kodak Stereo camera would have been a camera of desire in the mid-19th Century. But now? In a time where the vast majority of humans equate idealized, hyper-realism with great photography? The Ford MVP is going to offer the opposite.

Fortunately, folly will always find a home at ULTRAsomething — because every fool needs a paradise.

Final Ratings:

Personal Enjoyment Factor : 7. It would have been an “8,” but I dinged it a point for the mindful vigilance required to keep the camera upright, so the rewind crank remains intact. Viewing its photos is also quite enjoyable if, like me, your tastes reside on the outskirts of sanity. The MVP is like many of my favourite, no-budget, 1970’s drive-in movies — so bad it’s good.

Convenience : 8. Sure, it could be more convenient if, instead of manually setting the exposure via pictograph, the camera set it automatically. Then again, imprecise exposure is part and parcel of the camera’s gestalt, so any auto-exposure feature would need to include an element of randomness… which, come to think of it, would definitely be a camera I’d buy.

Long Term Potential : A safe and natural alternative to antipsychotic medications. As someone who has a tendency to occasionally step into a quagmire of banality and literalism and grow woefully depressed because of it, I need only point this camera at the most tiresome and vapid of subjects, look at the prints, and be instantly pulled from my moronic morass.

© 2022 grEGORy simpson

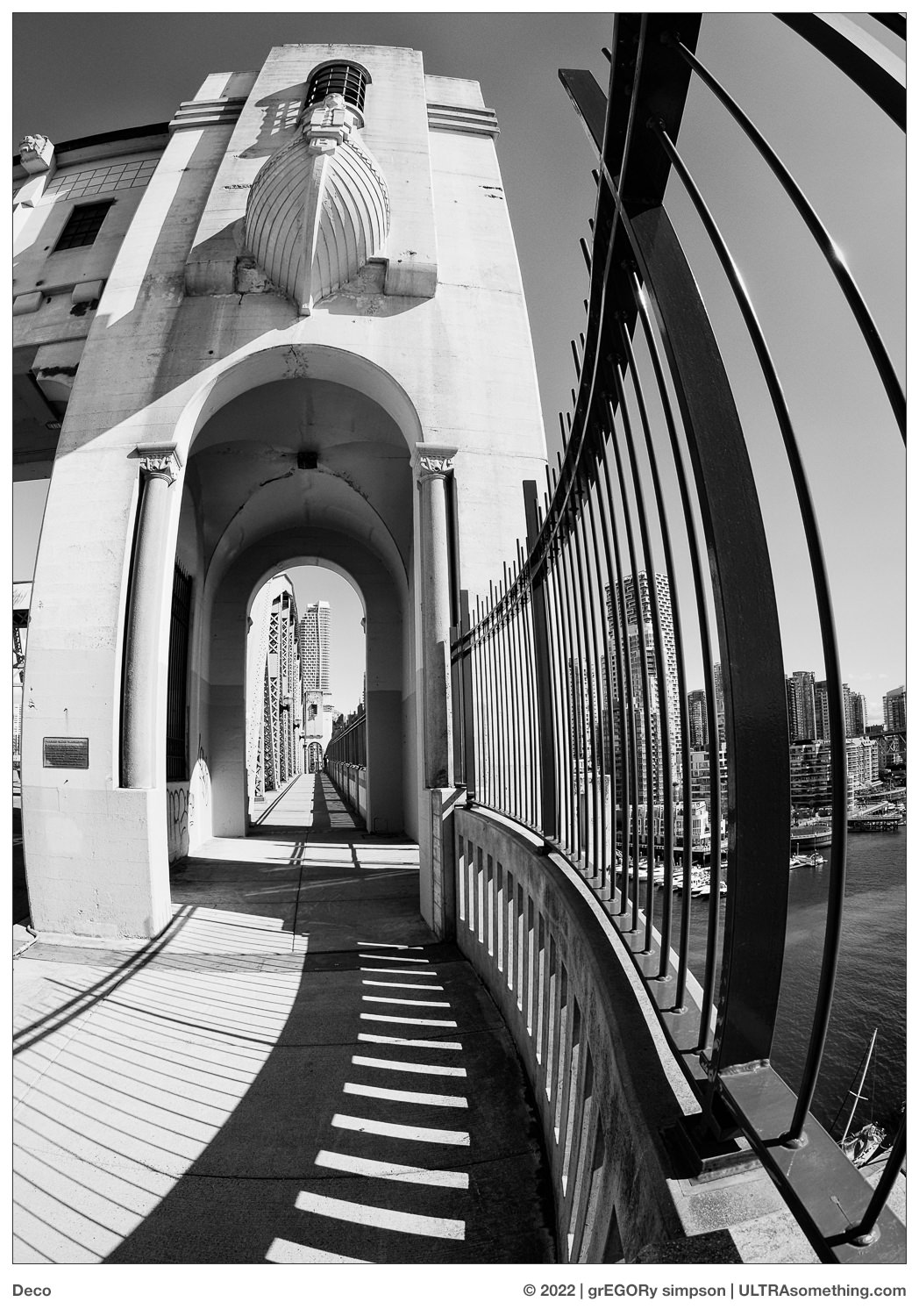

ABOUT THE ARTICLE : This is the final instalment in a trilogy of articles exploring cameras that are totally at odds with the expectations and demands of 21st Century life. The first was here, and the second was here. Many of you will be pleased to learn that, were it not for my heartless ability to exclude several worthy contenders (including the Insta360, a sample of which is seen to the right), this “trilogy” could easily have turned into an extended “series.” You’re welcome.

Regarding that Ford JBL Audio Systems tear sheet: Toward the end of my time at the company, there was actually a brief collision between my audio design duties and Ford’s marketing department. This glaringly patriarchal ad, which I assure you I had no hand in creating, ran in all the major stereo and hifi magazines that year. Alas, though my hand wasn’t in the ad, the same can’t be said for my face, which is on the far left, looking so very… um… I’m lost for an adjective here. I was paid $1 for the shoot, which marked both the beginning and the end of my professional modelling career.

REMINDER: If you’ve managed to extract a modicum of enjoyment from the plethora of material contained on this site, please consider making a DONATION to its continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site. Serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls — even the silly stuff.