There are countless ways that photographers can exhibit their photos. Online sharing sites are, of course, the most popular technique, but other possibilities abound. This article discusses two such possibilities — both of which share an unexpected connection to ULTRAsomething.

The Metal Print

Metal prints have been wildly popular for the past several years, and many photographers have at least dabbled in the creation of a metal print or two.

Metal prints have been wildly popular for the past several years, and many photographers have at least dabbled in the creation of a metal print or two.

I dunno. Maybe it’s the curmudgeon in me; or perhaps it’s simply that I have a modicum of taste — but I’ve just never felt the need to trundle down to the corner drug store and have ’em slap one of my photos onto a sheet of razor-sharp aluminum. And as long as I’m at it — ceramic coffee mugs, canvas tote bags, cork coasters, neoprene mouse pads, plastic luggage tags and silicon smart-phone cases are also all “on notice.” I happen to believe that the best receptacle for a photographic print is a nice, white sheet of quality paper. Metal? Sheesh, that’s for license plates.

Which brings me to my first public mea culpa of the year — after nearly a decade of resistance, I’ve acquiesced to a client’s request for a metallic version of a photograph.

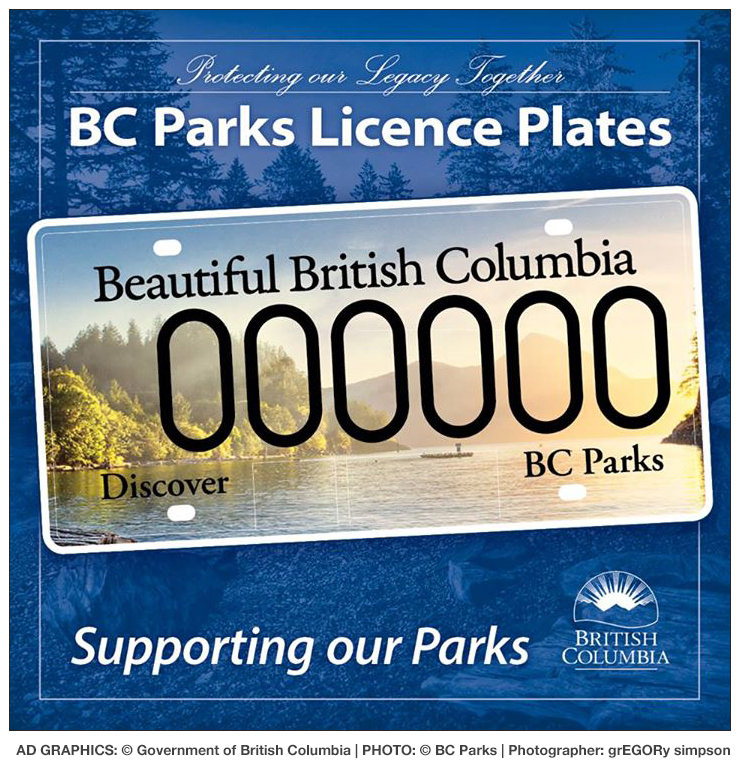

The client? The Province of British Columbia.

The destination of said metal print? A license plate.

OK. So it’s not a mea culpa as much as an admission that British Columbia managed to call my bluff.

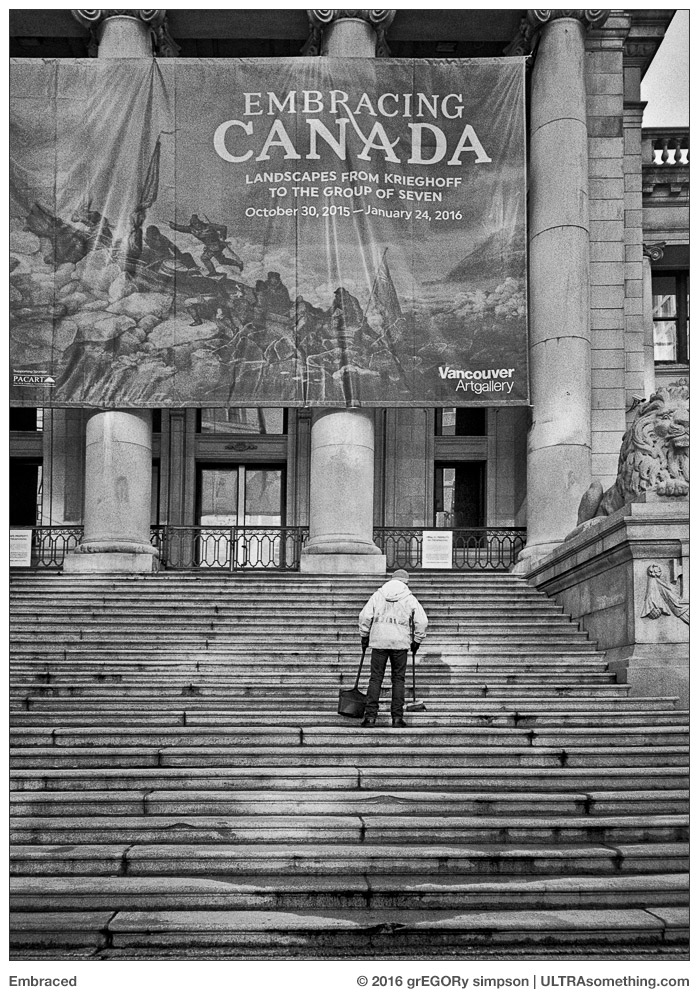

Apparently the province is issuing a new set of vanity plates for anyone who wishes to adorn their vehicle with something other than the standard string of dark blue, random alphanumerics on a white background. Instead, BC residents can now order a license plate with their choice of three photos: Porteau Cove Provincial Park, The Purcell Mountains, or a Kermode bear.

Here’s the LINK.

The Porteau Cove photo is mine. Well, technically, the copyright belongs to BC Parks — meaning it’s theirs to do with as they please, which apparently includes stamping it on a license plate.

I took it in the summer of 2008, in the waning days of my commercial photography “career.” Surprisingly, I have a rather vivid memory of the surrounding circumstances. It was late in the evening, and I could tell the sun would eventually set behind a nearby hillside. I knew, if I was lucky, that the sun’s rays would reflect off the sea mist and flare across the lens, rendering a “painterly” effect.

In spite of this, I nearly packed it in early. If I left before sunset, I’d be home by 10:30pm — a “short” 16 hour day. If I waited to take the sunset and twilight shots, I wouldn’t make it home until after midnight.

“Who really needs to see another hackneyed sunset photo?” I asked myself.

Nine times out of ten, I would probably have answered “no one,” packed up my gear, hiked back to the car and left for home. But today was different — I had a wicked, horrible migraine. I was actually in too much pain to drive; much less traipse a mile back to the car. If I waited and left after sunset, the soothing blanket of darkness would give me a tiny chance to better endure the drive. So, coiled in a fetal position around my tripod, remote shutter release in my hand, I decided I might as well go ahead and take that blasted photo.

And that blasted photo is now a license plate. I can’t really claim that I’m proud of this fact, but I’m certainly amused.

The Magazine

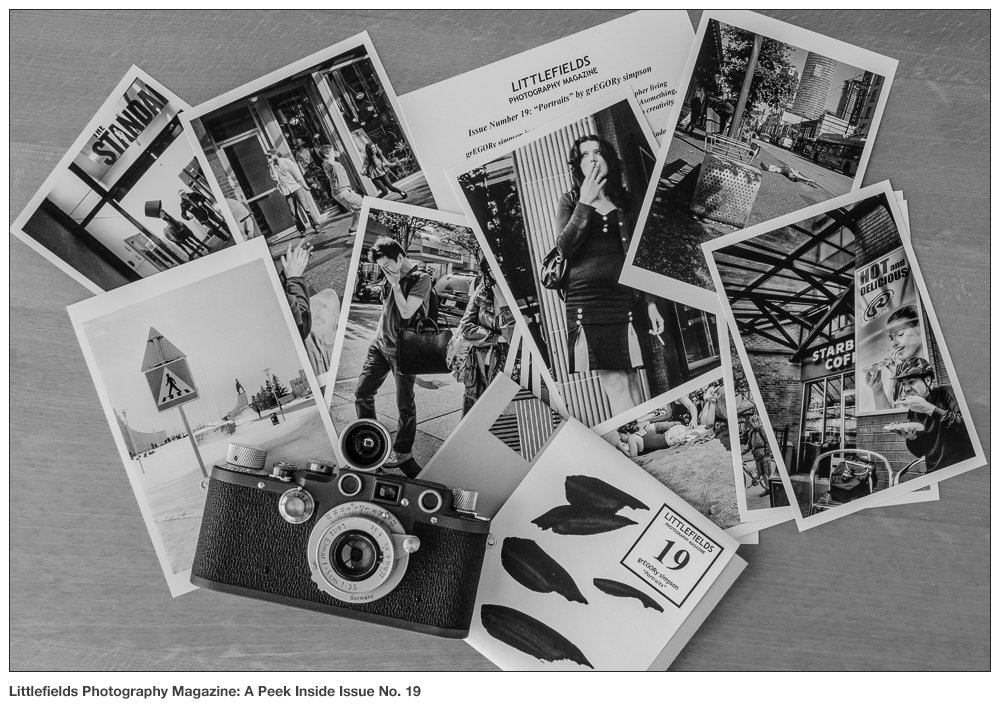

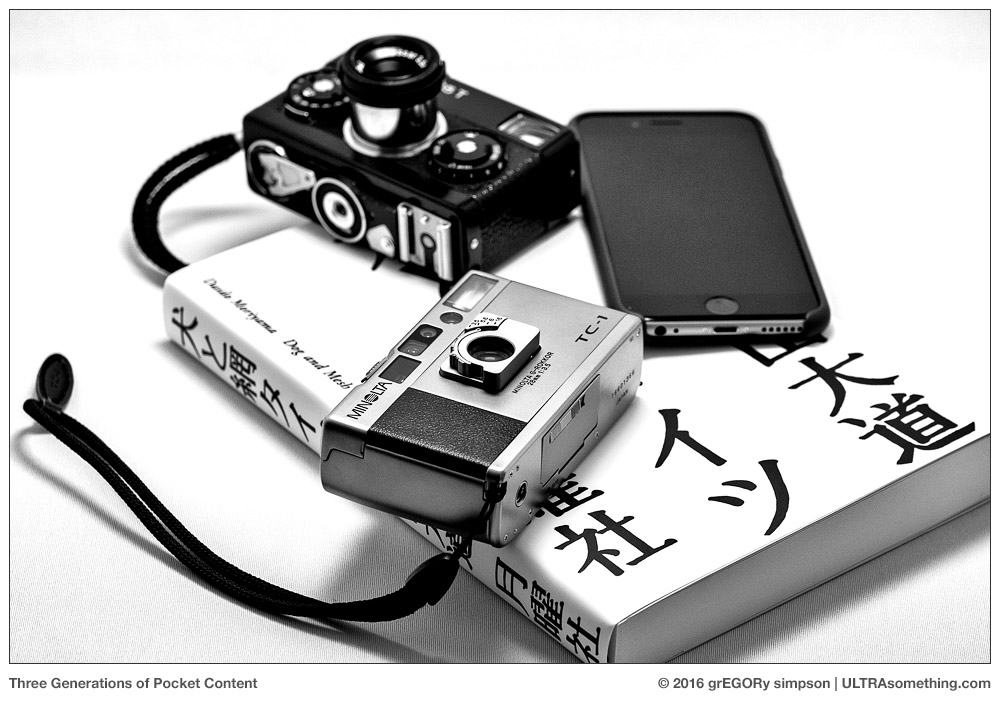

A few years back, I wrote a review of a new photography magazine called “Littlefields.” Technically, it was a review of the Littlefields concept more than of the magazine itself. I admired editor Jim Clinefelter’s courage to sell physical content in a digital content world. I admired the quality and diversity of the work contained within, and I admired the format itself — a small stack of 4 x 6 prints, culled (usually) from a larger selection of prints, which decreased the likelihood that any two issues would be exactly alike.

I admitted to a modicum of envy. Releasing my own work in printed, serialized form had long been a fantasy of mine, but I lacked the courage to buck the online distribution trend. Besides it was already hard enough getting people to engage with my content. To suddenly ask people to pay for photos (even if they were printed) just seemed like an insurmountable hurdle. So, after initially being encouraged by the Littlefields model and re-visiting my designs for a small, quarterly “accordion” style magazine, I went back to the simplicity of chucking my stuff up on the ULTRAsomething site.

I am thus pleased to announce that, in spite of my cowardice, some of my photos will soon be appearing in an actual photo magazine. And that magazine is… Littlefields!

Yup. Issue 19 is dedicated entirely to the photography of yours truly. So if you’ve ever dreamed of owning a few printed ULTRAsomething photos (even if they are only 4 x 6), now’s your chance to get TEN of ’em in one package.

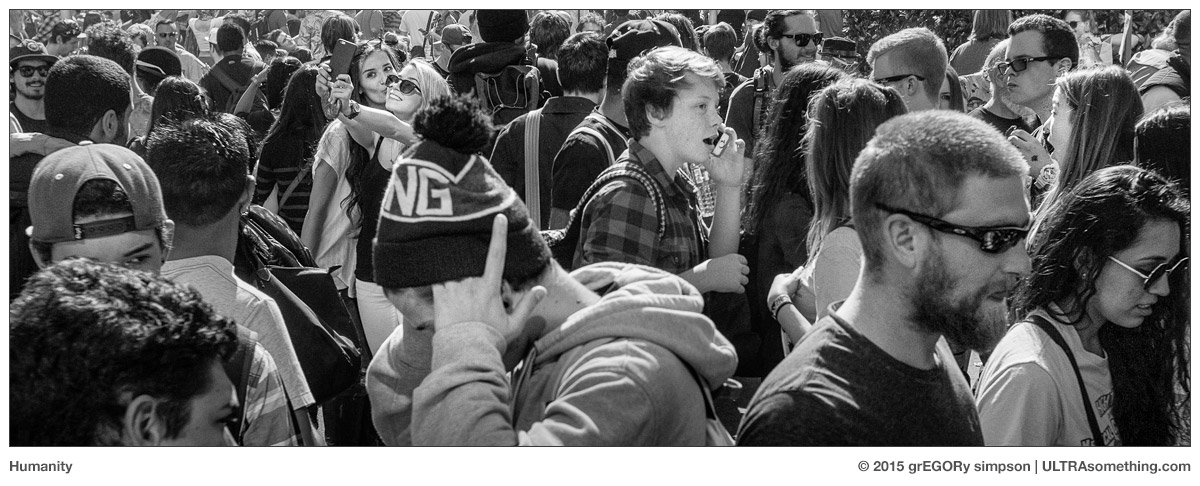

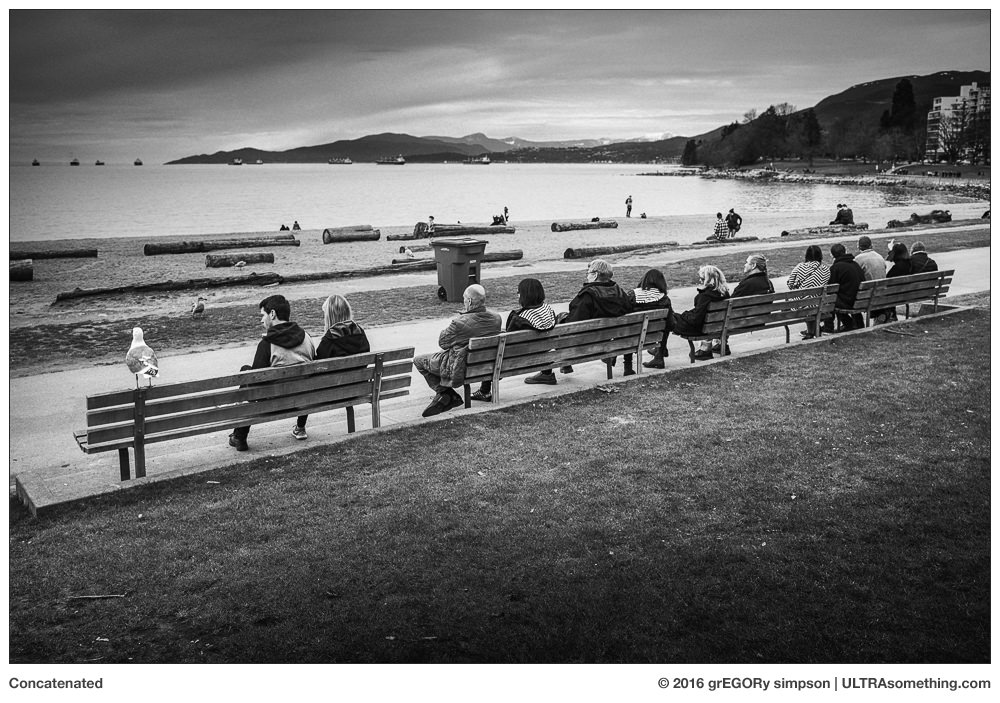

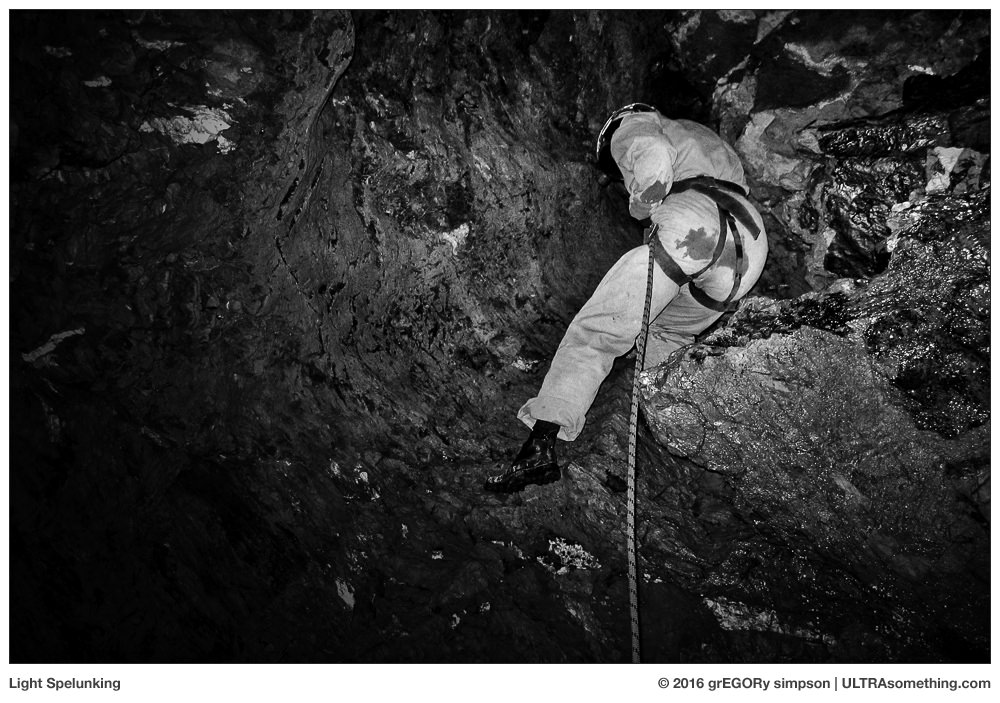

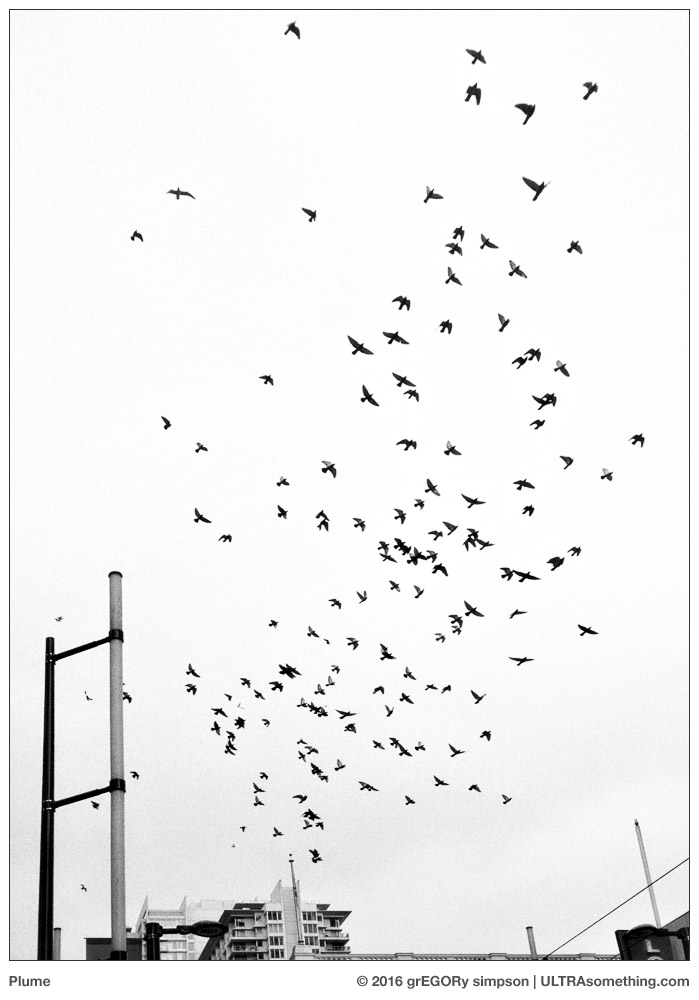

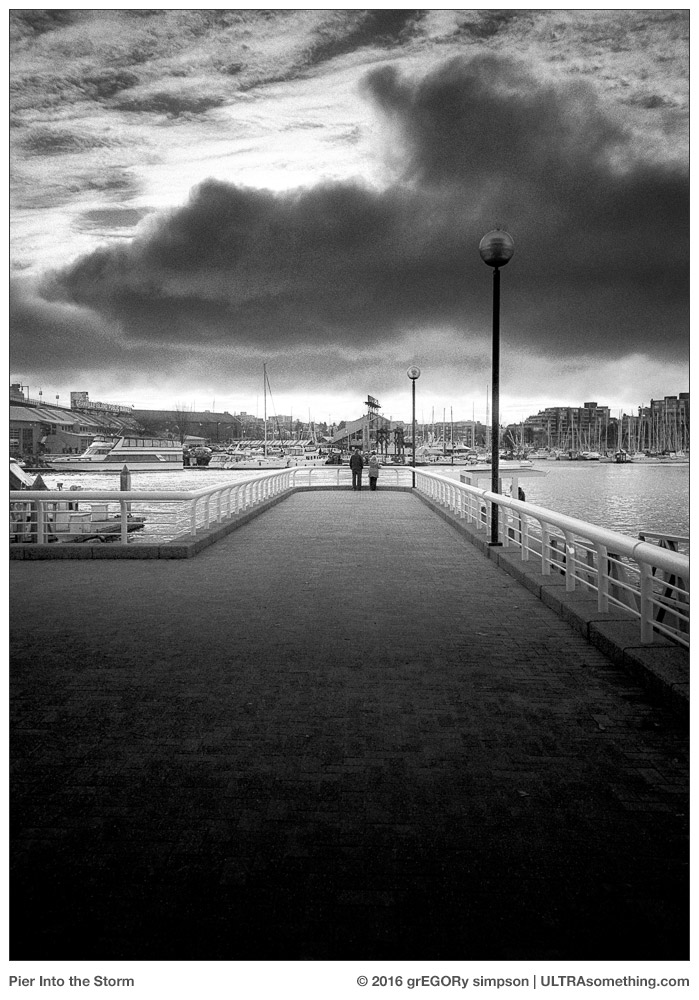

Since Littlefields requested that the images conform to some sort of theme, I chose “portraits.” If I were any good at lying, I’d claim to have curated the photos such that, in their entirety, they formed a ‘portrait’ of mankind. The truth, however, is far more fundamental — I simply chose to include only photos that were taller than they were wide — “portrait-oriented” photos.

I provided Littlefields with a master pool of 20 photos. In classic Littlefields fashion, each issue of the magazine will ship with a random selection of 10 images, meaning if you buy one issue for yourself, one for your spouse, one for your parents and another for your in-laws, each of you will get a magazine with a slightly different selection of photos.

Anyone interested in owning what will surely become a valuable asset (I am, after all, on a license plate), should pop on over to the Littlefields site and buy an issue or two. Heck, while you’re there, why not check out some of the available back issues?

Personally, I’m hoping this issue sets a new sales record for Littlefields. That way, the magazine will be forced to publish a second collection of my photos. Should that happen, I’ve cleverly decided that the next theme will be “landscapes” — and I don’t mean the sort that wind up adorning a BC license plate.

©2017 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THE PHOTOS:

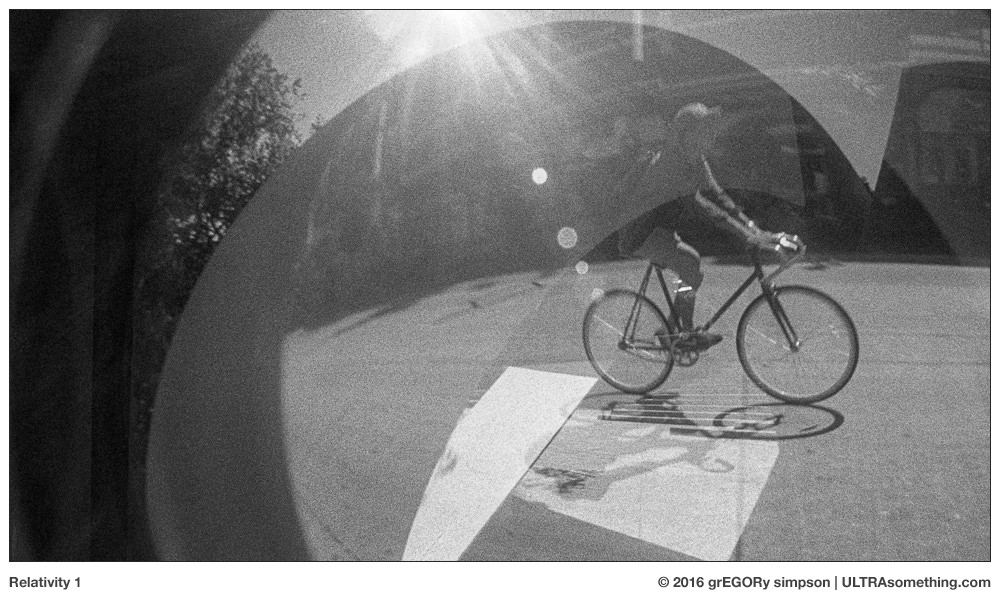

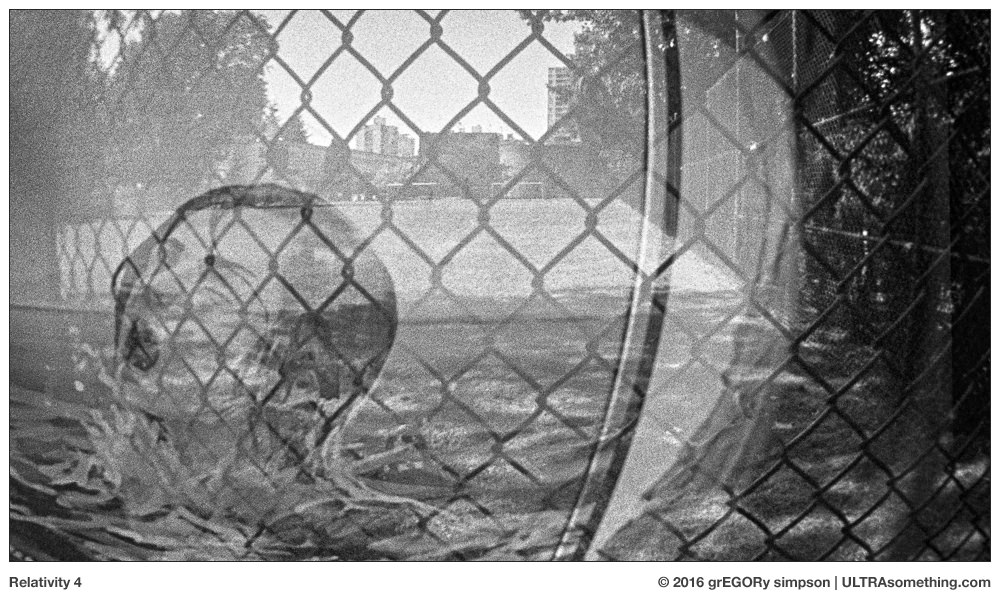

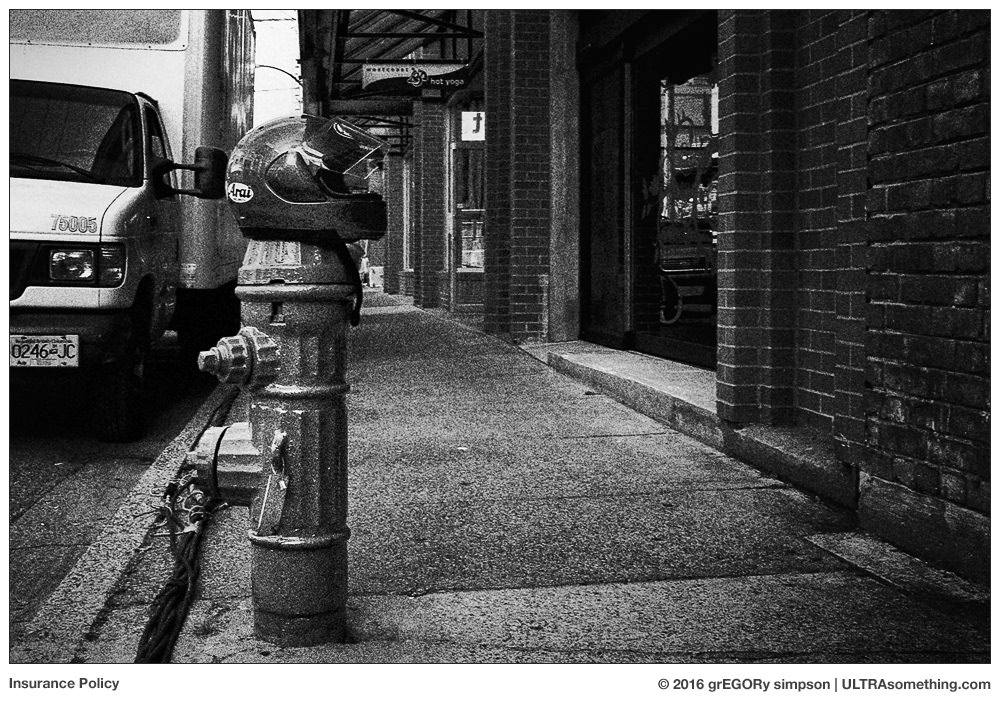

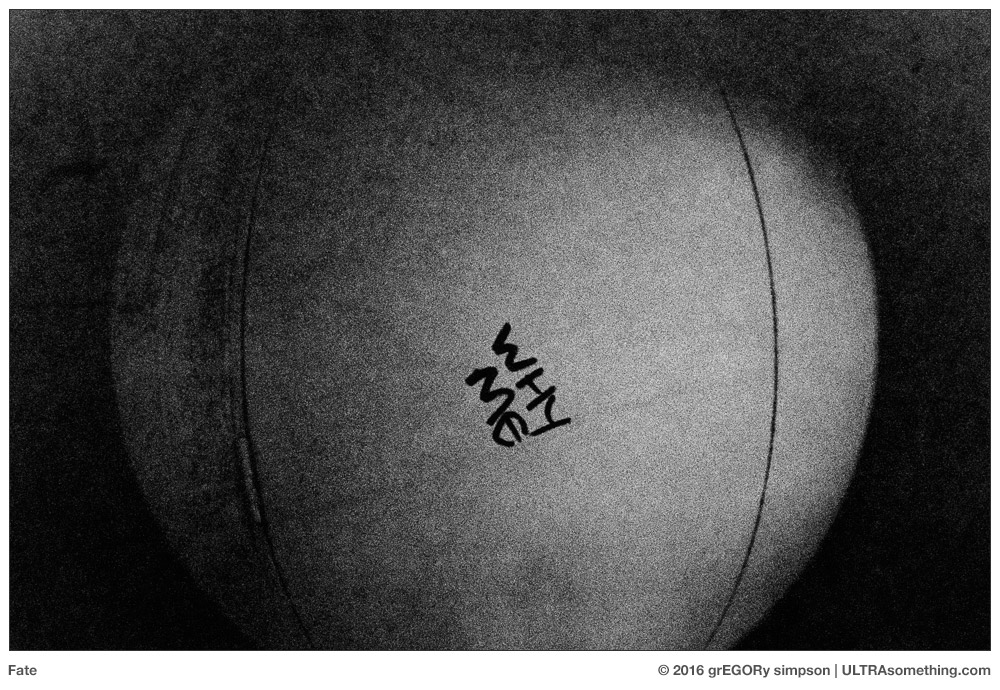

“Happy Hour” was shot with a Leica M (Type 246) Monochrom with a 21mm f/3.4 Super-Elmar lens, whilst “A Complex Relationship” came courtesy of the Ricoh GR.

I snatched the BC Parks License Plate ad off some official government website. Hopefully, no one in the BC government will find cause to complain — after all, my contract did include the right to publish my own BC Parks photos for “self promotional” purposes. Though, admittedly, I’m not sure exactly what I’m promoting. Perhaps it’s my ‘skill’ as a license plate photographer? In which case, I hereby announce that I’m willing to entertain any and all offers to travel to exciting or beautiful destinations worldwide for the purpose of taking your license plate photo! There… that should satisfy my legal obligation to “self promote…”

REMINDER: If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.