I’m supine in a pale blue vinyl chair: fists clenched; toes curled and mouth agape. The whine of the dental hygienist’s hypersonic cleaning tool harmonizes with the gurgling rumble of the vacuum tube suctioning saliva from my throat.

The hygienist leans back slightly, exercising her neck to-and-fro before pausing in mid-stretch to fix her gaze upon my camera, which sits atop my jacket on a counter near my feet.

“Don’t you photographers think life would be more interesting if you actually experienced it, rather than watching it through a viewfinder?” she asked in a tone more accusatory than questioning.

I was speechless. Mostly because her hands were jammed into my mouth, but also because I simply don’t know how to answer a question that’s based entirely on the presumption of two falsities.

Falsity #1 is to assume, just because I have a camera, that I’m a photographer. I’m not. And I know this because every time I see an article titled “10 photos every photographer should know how to take,” I quickly ascertain that I have absolutely no desire to take any of them. Plus, I’d be willing to wager a months’ income that I take fewer photos in a year than any iPhone-toting 20-something dental hygienist.

Falsity #2 is that I walk around looking at the world through a video screen or peering through a viewfinder. All totalled, given the paucity of my output and my own shooting habits, I probably spend less than 5 minutes a month looking through a viewfinder. My camera is an accomplice on my journeys, not a portal through which I experience them. The camera is lifted to my eye only in that brief instant that I wish to frame something intriguing within its rigid rectangular cell — incarcerating it; imprisoning it for future study.

So after removing the fabricated presumptions, her real question should be, “does that camera you always carry around diminish your ability to see and experience your surroundings?”

And the answer, of course, is “No. Just the opposite.” Or, as I eventually muttered to my hygienist, “Mo. Muff vah ahm pah feff.”

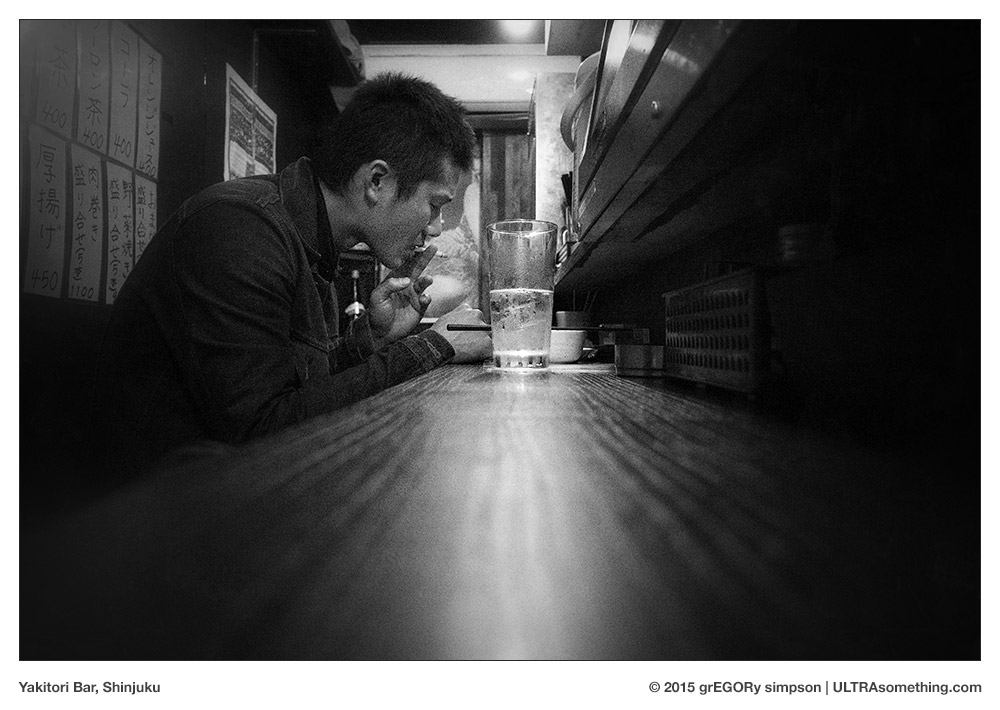

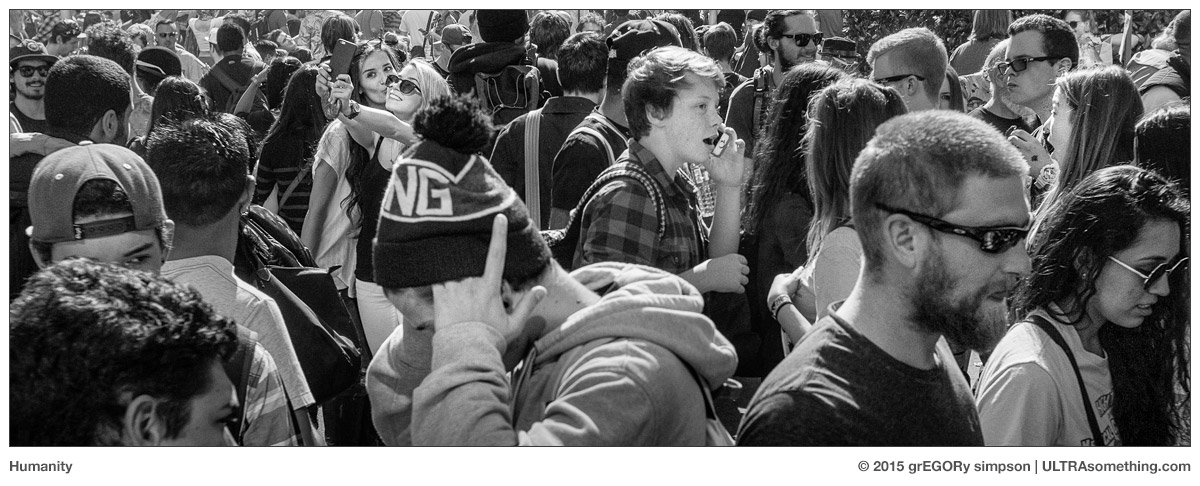

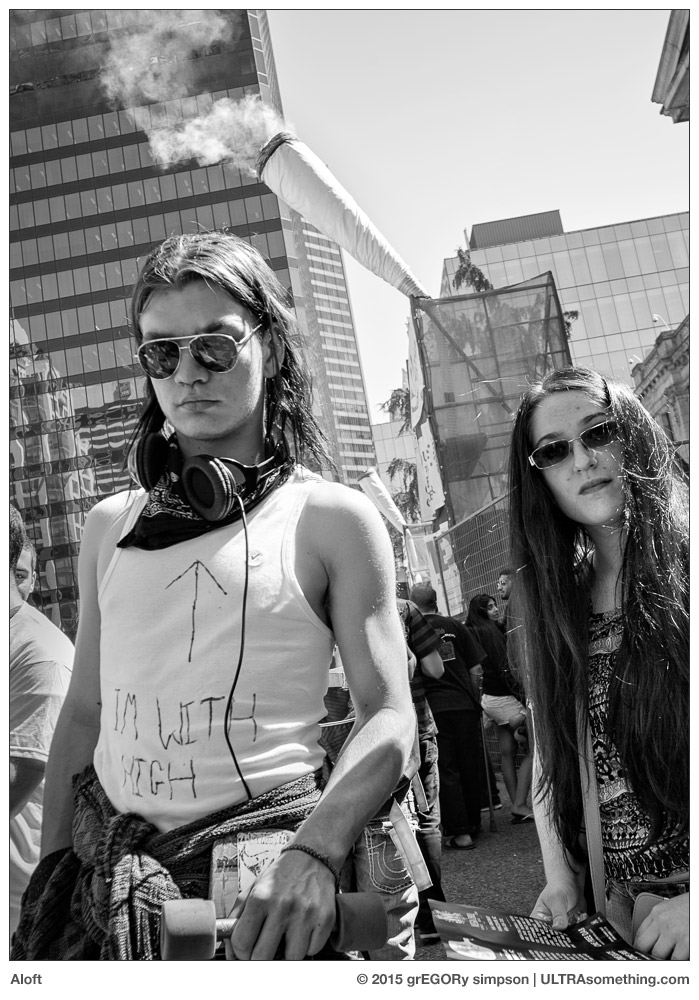

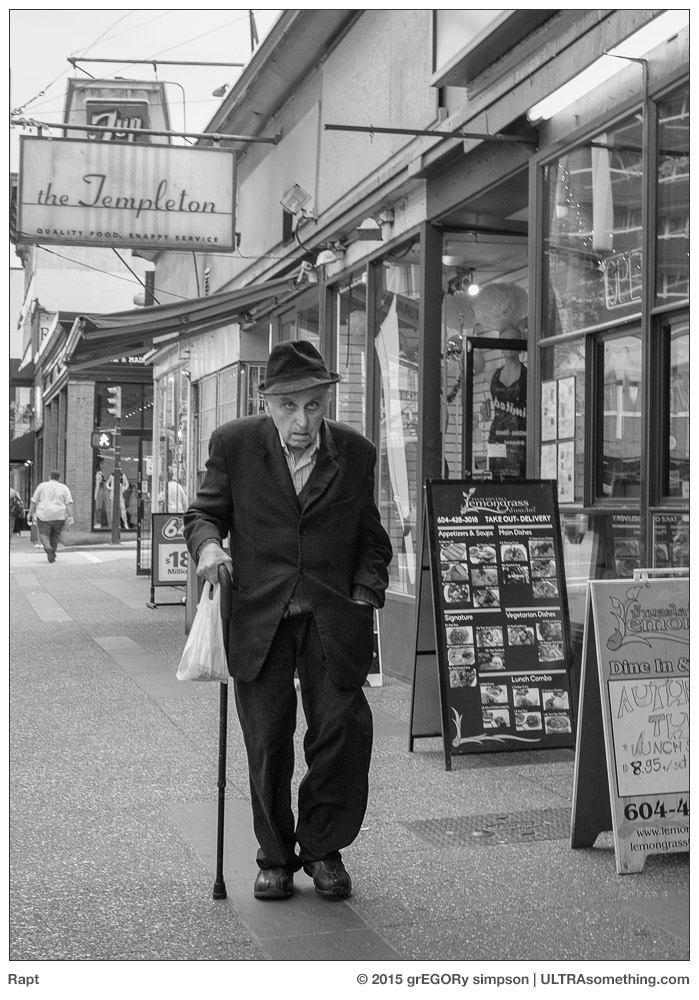

Carrying a camera liberates you. It sharpens your eye; heightens your senses and increases your spatial awareness. With a camera, I see beyond the mass of humanity on a packed sidewalk in Shibuya — past the throngs to a single individual, who unmasks himself just long enough to take a drag on a cigarette — a delightfully playful “nine lives” sign in the foreground.

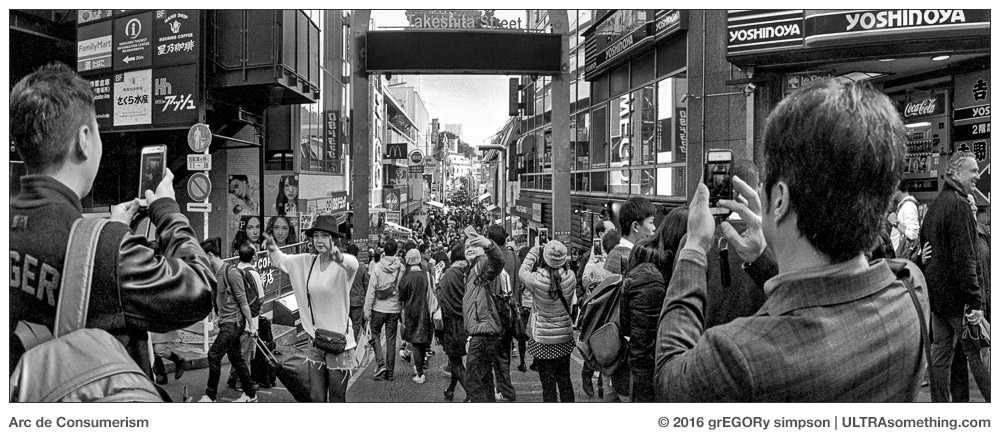

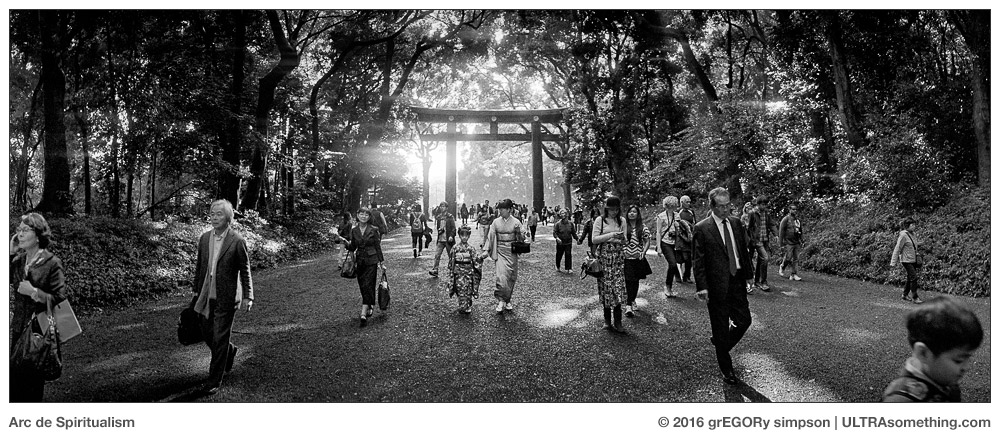

The camera helps me understand that the best way to remember the incongruously out-of-place architecture of Harajuku station is not to take a hackneyed shot of the station, but to photograph the effect it has on others who see it.

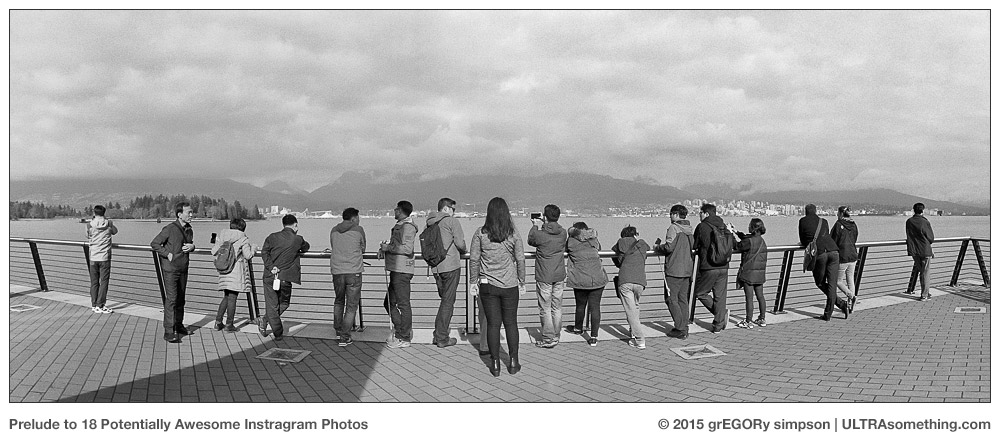

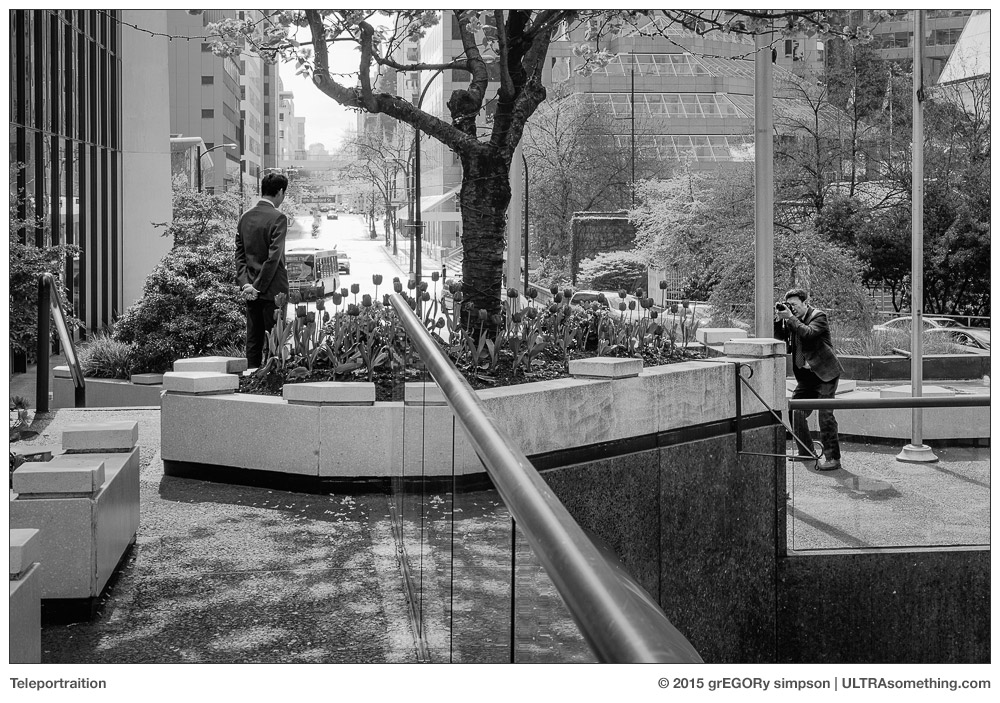

Cameras teach me to watch the watchers.

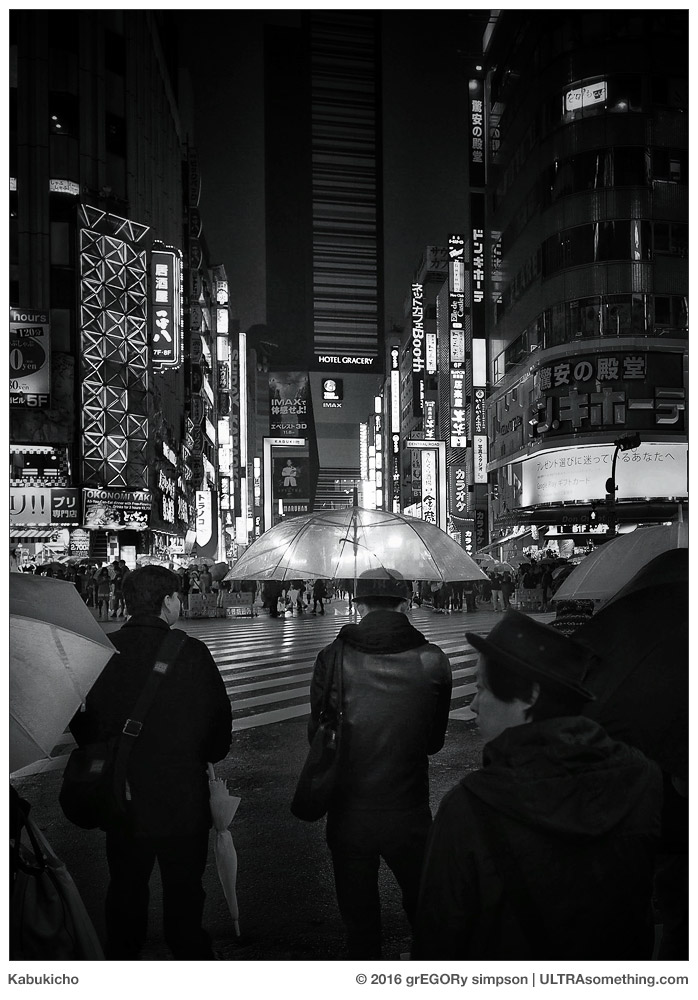

If I didn’t carry a camera, would I have noticed that Tokyo’s ubiquitous clear plastic umbrellas glow like lanterns when backlit?

Would I have observed that those same umbrellas are festooned with tiny stars? Or that peering through one is like looking through a magic window that pierces a cloud-covered sky?

Would I be dazzled by the shapes and shadows cast by something as inconsequential as a stairwell?

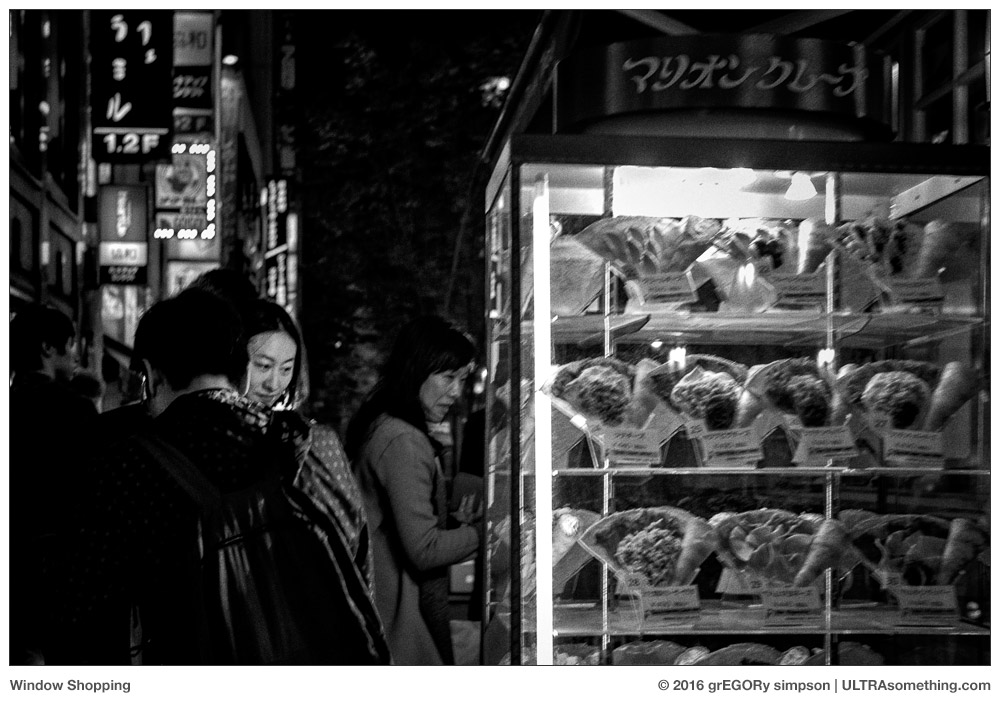

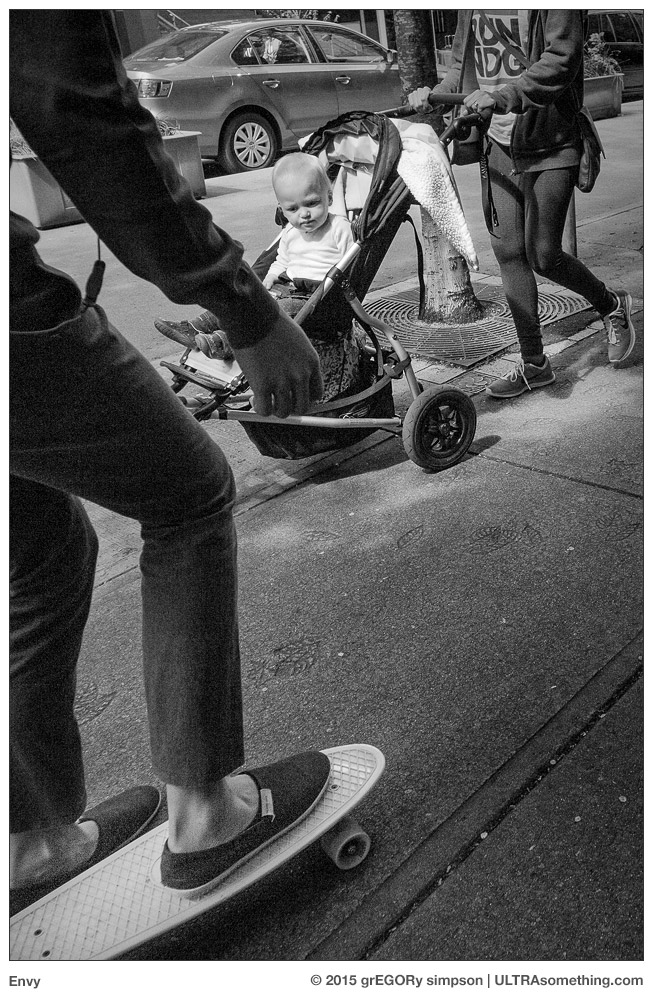

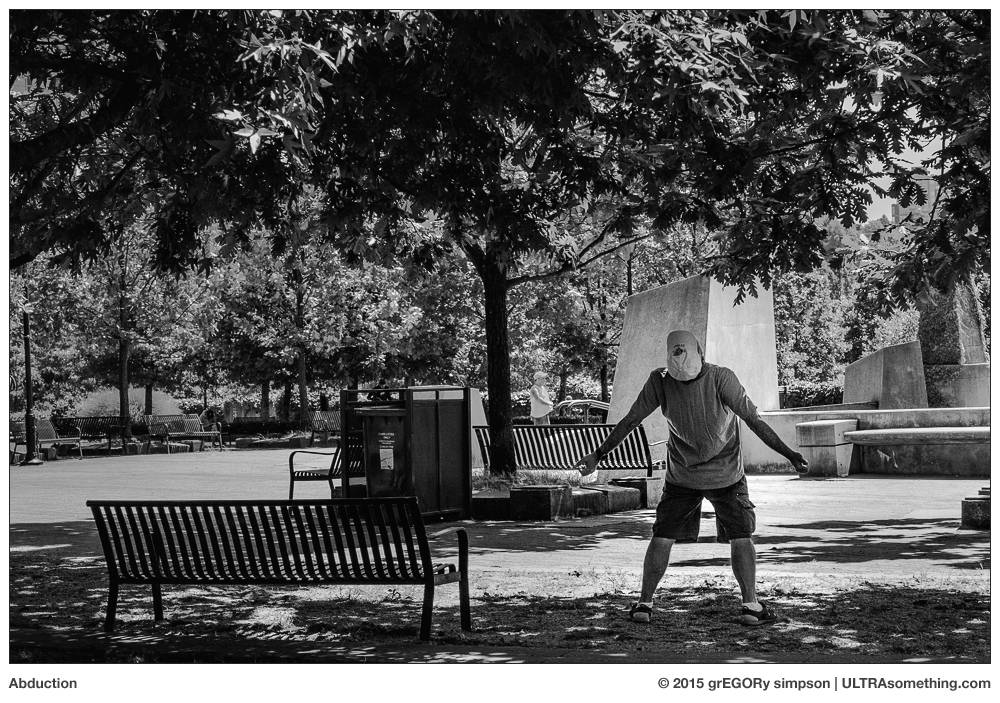

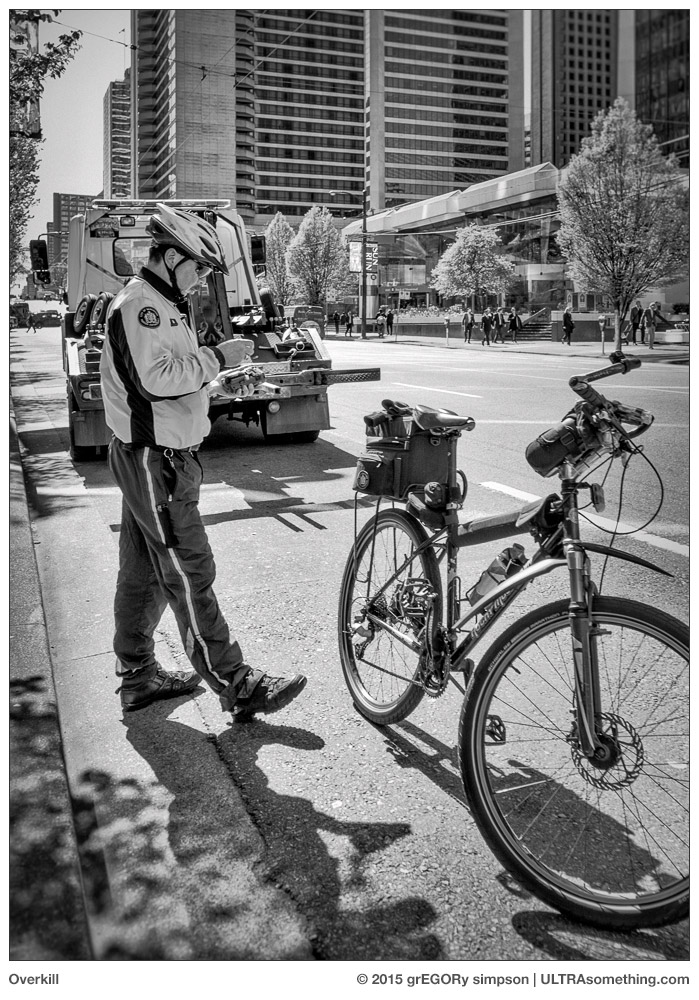

Or have become as hyper-aware of juxtaposition as I am now?

As attuned to human emotion?

It’s the camera that allows me to truly see — to truly experience all the subtle nuances that surround me each and every day.

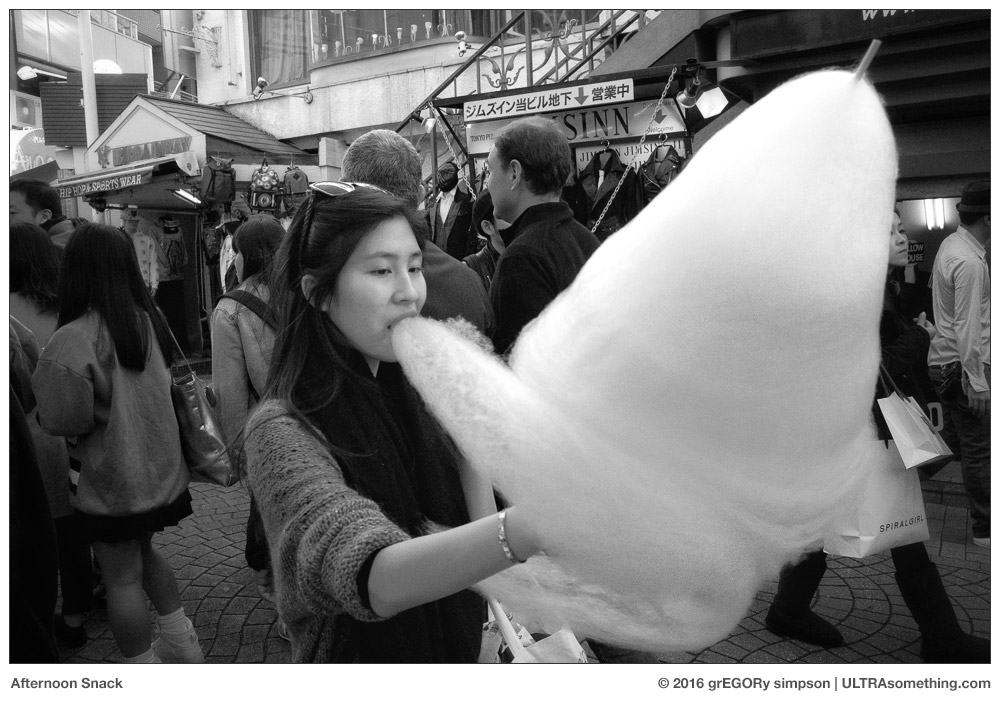

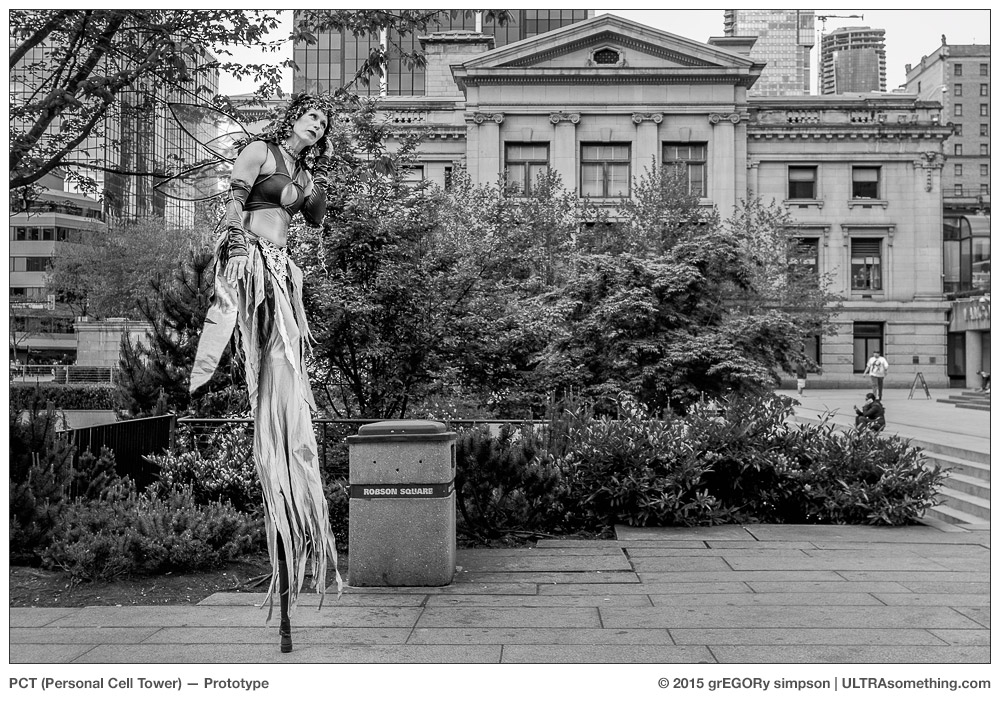

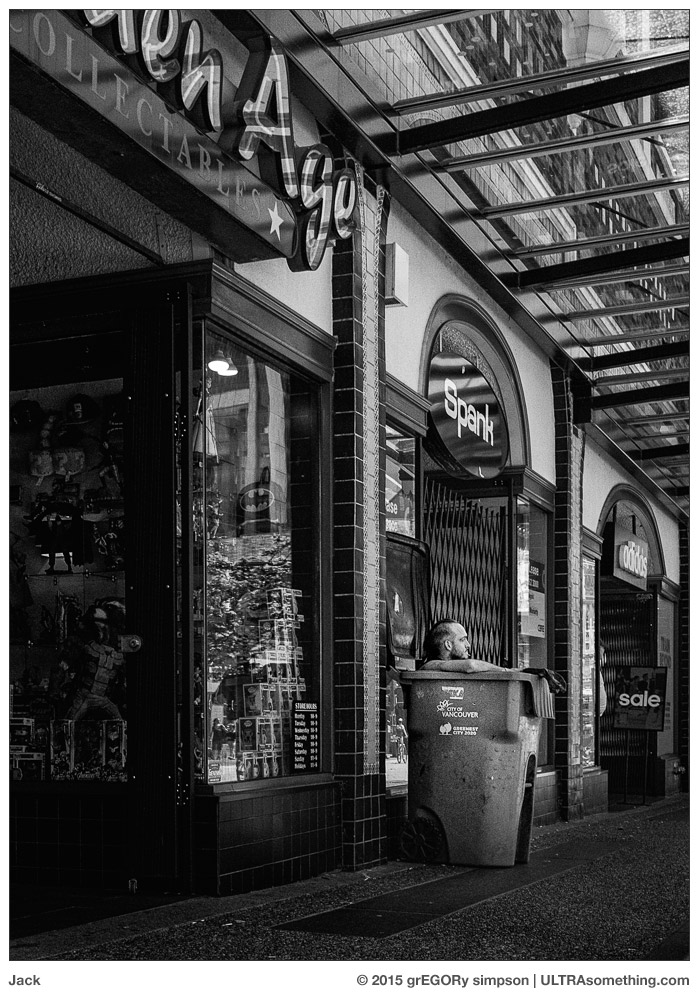

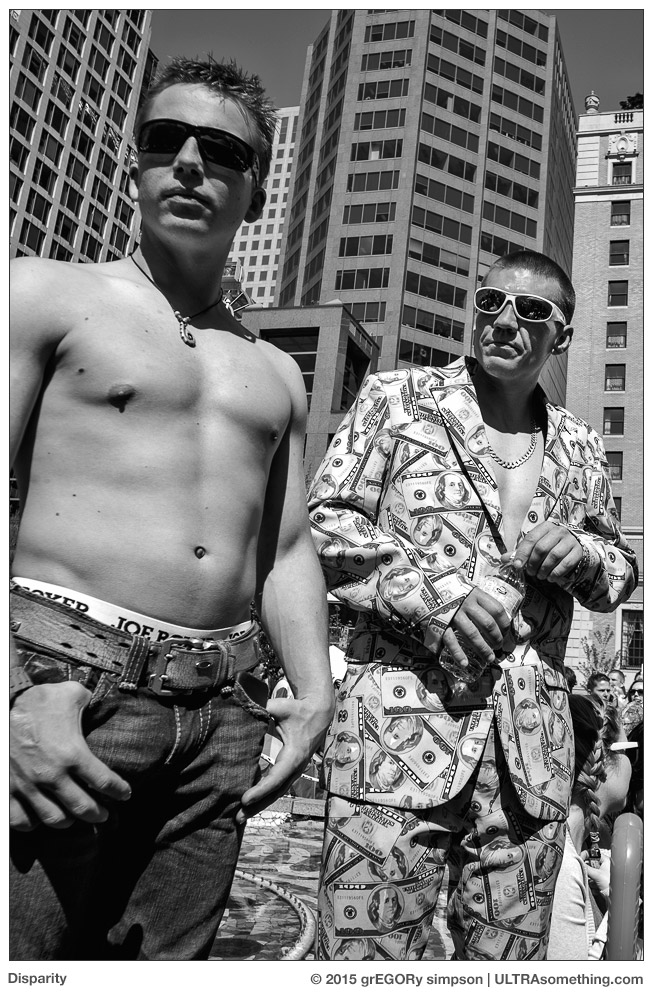

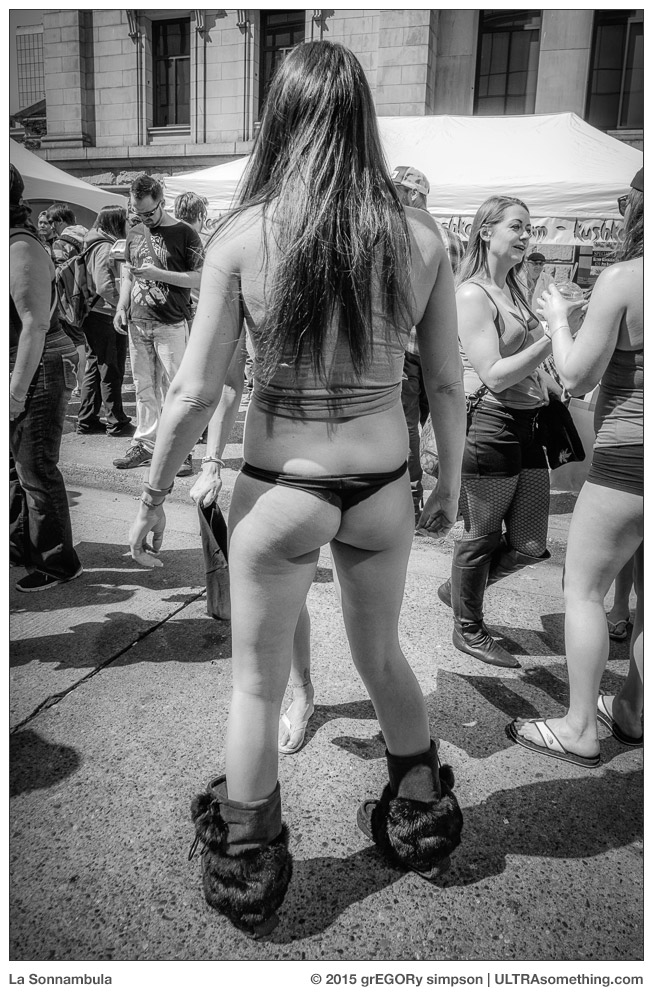

Of course, there are times when I witness events that require absolutely no astuteness whatsoever to appreciate. In such instances, carrying a camera might not help me to see, but it sure helps me to take a photograph.

But even in instances such these, one wonders if there isn’t still an instinctual element at work — one in which intuition and subliminal suggestion are allowed into the subconscious? The subject of the previous photo is, indeed, obvious. And I had numerous opportunities to take it — yet I chose exactly this moment to do so. Why? Perhaps the clue lies at the far right edge of the frame… Yes, cameras even teach you to see and respond to subtleties that your conscious mind simply doesn’t have time to rationalize.

So, would life be more interesting without a camera? I can’t answer for others, but for me, the answer is an emphatic “no.”

©2016 grEGORy simpson

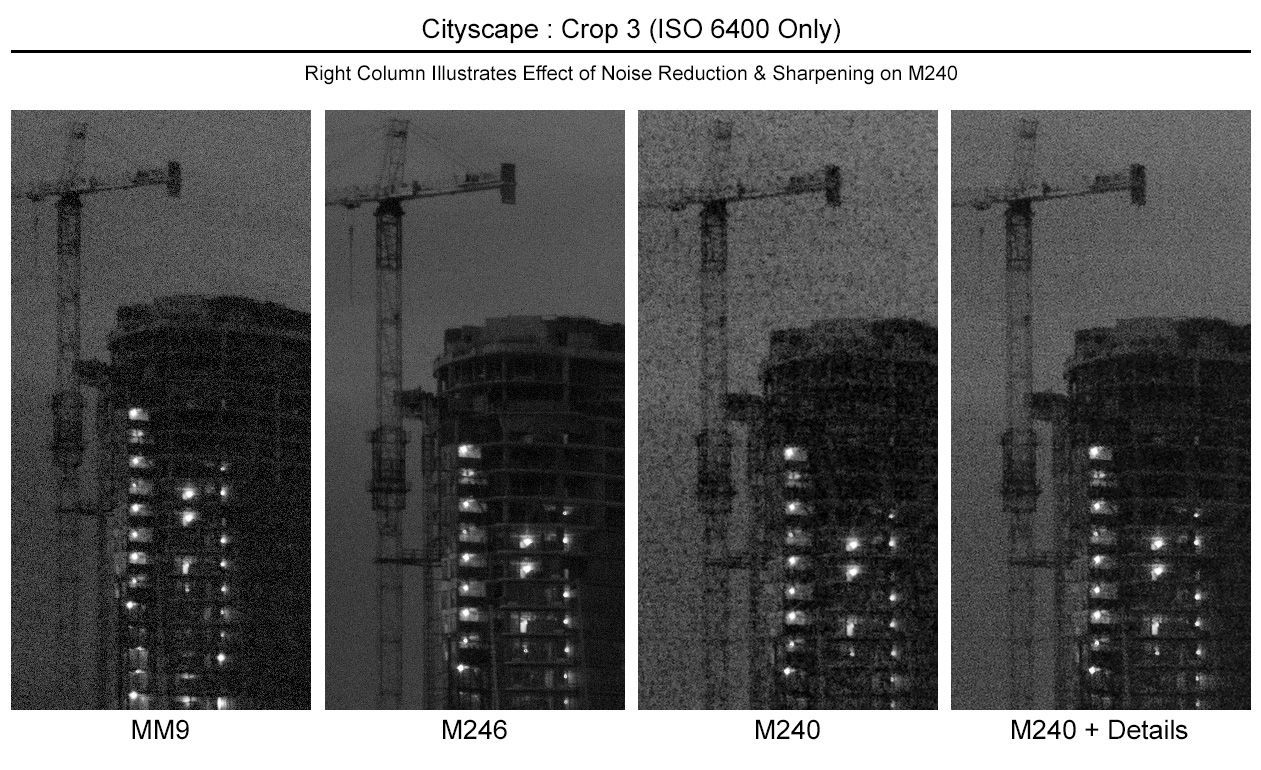

ABOUT THE PHOTOS:

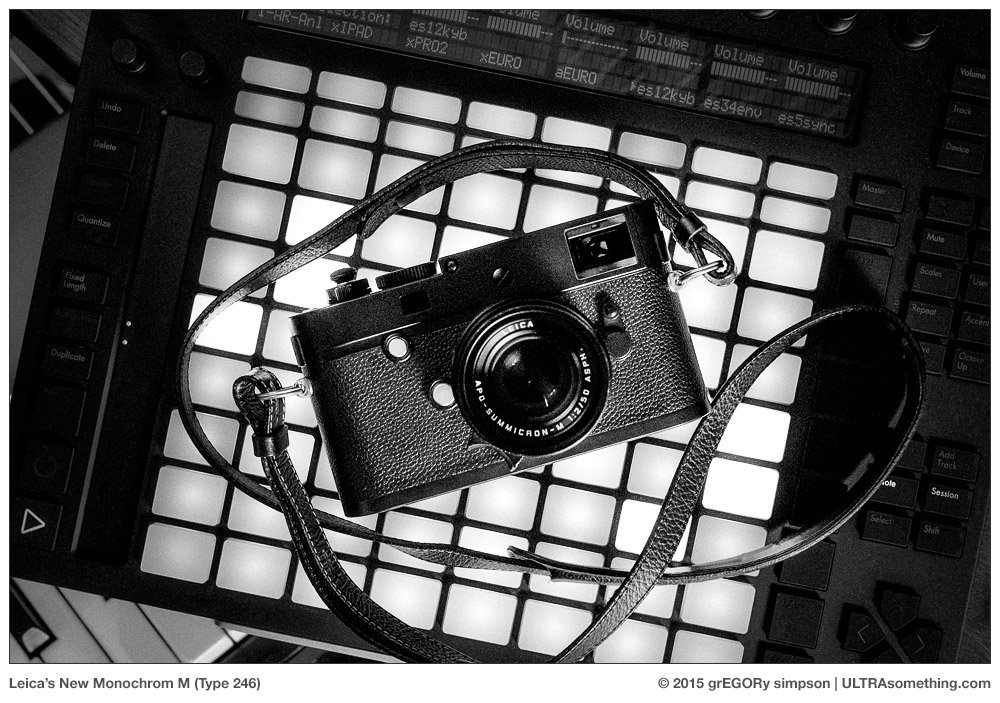

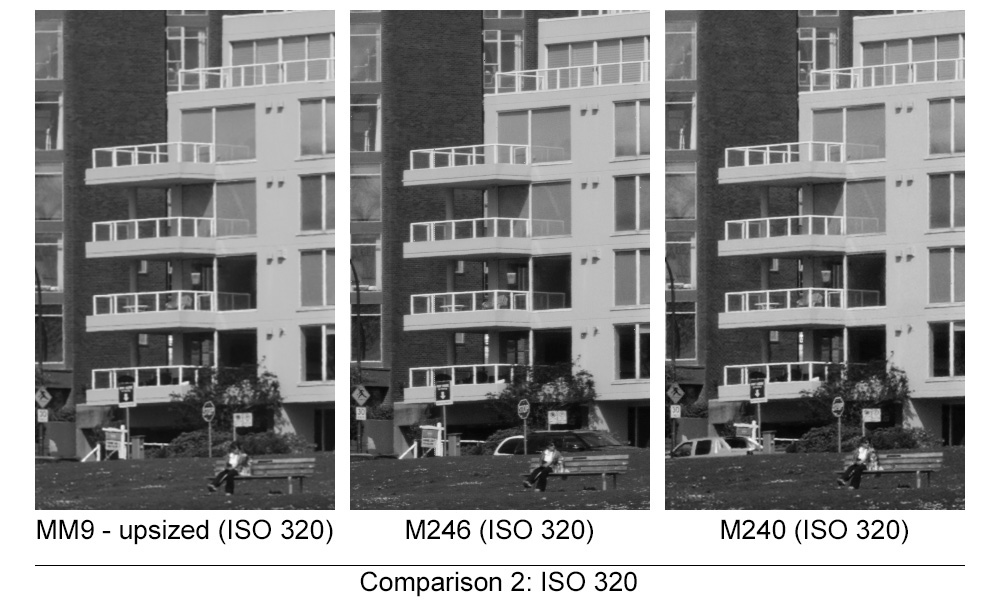

All of these photos were taken on a recent trip to Tokyo and represent the tip of a still-uncurrated iceberg of images. Unfortunately, even though I brought only two lenses to use with my Leica M Monochrom (Type 246), I seemed to have been rather lax at recording which lens I used for which shots. For example, “Shopping Spree” was definitely shot with a Leica 21mm f/3.4 Super-Elmar ASPH lens, but the embedded EXIF data says I used my 35mm Summicron. Note that this is not a Leica bug — it’s an Egor bug. Because the majority of my rangefinder lenses are not coded, I disable the camera’s “auto lens detection” mode, and manually enter the lens type each time I mount a different one. At least that’s what I do in theory. Alas, such was not the case in Tokyo. So, even though “Nine Lives,” “The Art of Artistry,” “Stairway, Shinjuku,” “Chicken or Egg?” and “Window Shopping” were also all shot with the Leica M Monochrom (Type 246), I can’t say for certain whether each uses the 21mm Super-Elmar or the 35mm f/2 Summicron (v4) lens — though the racially different perspectives afforded by these two focal lengths does make it fairly easy to make educated guesses.

“Kabukicho” and “Stargazing” were both photographed under heavy drizzle, so the weather-sealed Olympus OM-D E-M1 was used, along with the Olympus 12mm f/2 lens. Note that the 12mm lens is not, itself, weather sealed — but I’ve never had any issue carrying the camera with the lens pointing down — wiping everything dry now and then with a chamois.

“Room With a View” and “Afternoon Snack” both utilized the little Ricoh GR — which frequently rode shotgun whenever I carried the heavier and bulkier Widelux F7 panoramic film camera.

REMINDER: If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.