I am what I am. Unless I’m my doppelgänger — in which case I am what I’m not. Mercifully, my doppelgänger and I rarely travel in the same circles. It’s not that we purposely avoid one another, it’s just the natural result of our divergent interests.

Now and then, fate conspires to throw us together. These instances are not altogether unlike a horror movie — each of us wishing (and perhaps secretly plotting) for the other’s immediate demise. Alas, we have but one body to share between our oft-competing interests — to harm the other would only harm one’s self. So we endure.

It’s been several years since my doppelgänger and I last spent significant time together. But a recent trip to Iceland brought us together again — he with his yangs, and me with my yins.

“Hey,” he said, upon learning of our trip, “we’re going to Iceland — a beautiful country filled with beautiful landscapes that will yield a wealth of beautiful photos that many will admire.”

My inclination was somewhat different. “Hey, we’re going to Iceland — a beautiful country filled with beautiful landscapes that I’m free to enjoy while I go about my business of photographing something else entirely.”

Negotiation

The other Egor has a penchant for high-fidelity photographic banality, while I prefer a more impressionist approach. Our differences made it absolutely essential for the two of us to collaborate on a camera strategy. It would be a very long trip if we didn’t.

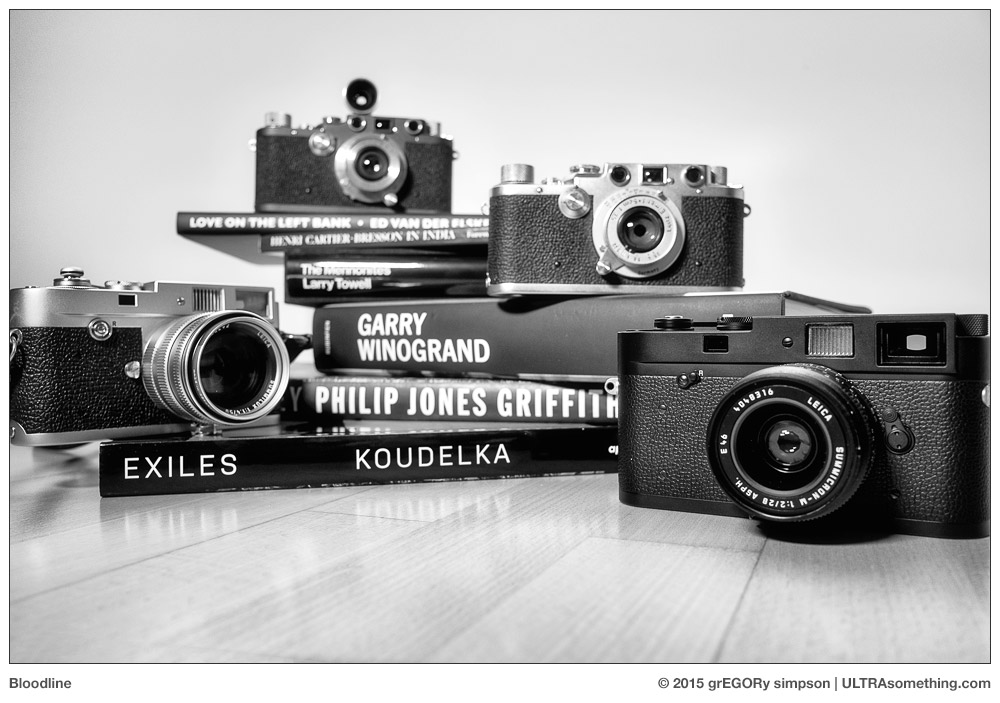

So a month before the trip, we got together over coffee and agreed on a plan — duelling Leica M’s. He would take the Leica M9. I would take the Leica M6 TTL. Digital precision for him. Film goodness for me. And we could share lenses. 2 cameras. One set of lenses. Easy.

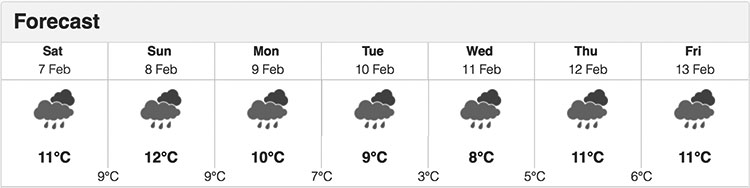

But in the days leading up to the journey, Iceland’s weather forecast grew increasingly more ominous. 100 km/hr winds; freezing temperatures; driving snow and sleet — all were expected during our time in Reykjavik.

Because the cameras were destined to get drenched, I decided to switch from the M6TTL (which contains a battery and electronic circuitry) to the M2 (which is purely mechanical). Doppelgor had no such Leica-centric alternative. The M9 definitely wouldn’t survive a deluge, and we didn’t own one of the newer, somewhat more weather-resistant Leicas.

So my “buddy” threw a wrench into our plans, and decided to travel with our only weather-sealed body — the Olympus OM-D E-M1. Although it’s perfectly possible to use an adapter to mount Leica M lenses on the OM-D, Doppelgor knew these lenses didn’t perform optimally with Micro Four-Thirds cameras — and since his dictate was to take the sort of sharp, technically precise photos that other people expected him to take, he dismissed the idea of sharing lenses with me.

Since Mr. Selfish was now hogging all the bag space with his Micro Four-Thirds lenses, there was no longer any room for my Leica glass. In a petulant burst of rebellion, I decided to take only my little Olympus Pen EE–2 — a fixed-lens, half-frame film camera that would slip into a jacket pocket, and thus not occupy any of the space now being appropriated by that digital oaf.

Since Mr. Selfish was now hogging all the bag space with his Micro Four-Thirds lenses, there was no longer any room for my Leica glass. In a petulant burst of rebellion, I decided to take only my little Olympus Pen EE–2 — a fixed-lens, half-frame film camera that would slip into a jacket pocket, and thus not occupy any of the space now being appropriated by that digital oaf.

The doppelgänger and I were, once again, no longer on speaking terms. But as the trip grew nearer, the weather forecast grew even more dire. So dire, in fact, that OM-D boy decided it would be too wet to risk carrying any lenses that weren’t, themselves, weather-sealed. But the only appropriate weather-sealed lens we own is the Olympus 12–40 f2.8 PRO — a zoom lens. If there’s one thing the two of us agree on, it’s that we absolutely despise zoom lenses.

Given our mutual dislike for zooms, it’s curious that either of us actually owns this lens. In reality, we bought it under the same dictate that compels most people to buy insurance — it’s something you own just in case you need it, but you hope you never actually have to use it.

So with a single zoom going in the bag and all the prime lenses staying home, there was suddenly a lot of space for extra gear. In a moment of rare cooperation (motivated, I’m sure, by our mutual disgust at having to travel with a zoom lens) we decided to share the remaining space. In a nod toward Doppelgor’s proclivities, I added the Hasselblad Xpan and its 45mm lens. In a nod toward mine, he added the pocketable little Ricoh GR.

We were ready.

“Which shoulder bag should we take?” I asked.

And then, suddenly, we weren’t ready anymore…

“Shoulder bag?” replied my other self. “We’re going to be hiking around Iceland in some rather inclement weather. A shoulder bag is going to be completely impractical. It’ll have to be a backpack.”

Frankly, I find backpacks to be a deterrent to photography. Shoulder bags give me quick access to anything I might need — it’s all right there, by my side, and in easy reach. Backpacks? No way. Carrying gear in a backpack is the same as not carrying gear at all. What use is the gear if you can’t get to it when you need it?

Frankly, I find backpacks to be a deterrent to photography. Shoulder bags give me quick access to anything I might need — it’s all right there, by my side, and in easy reach. Backpacks? No way. Carrying gear in a backpack is the same as not carrying gear at all. What use is the gear if you can’t get to it when you need it?

Still, Doppelgor had a valid point, and I was forced to grudgingly admit that a shoulder bag probably wasn’t going to cut it on this particular trip. Unfortunately, I had quietly disposed of all our backpacks 7 years ago, after finally convincing Doppelgor to ditch his SLRs.

Backpack-less, I called my local Lowepro rep, presented him with my seemingly impossible conflation of bag parameters and dictates, and asked for his recommendation. The next day, he graciously met me at a local coffee shop carrying two options for my consideration.

After a quick game of eenie-meenie-miney-moe, I chose the Photo Hatchback 16L AW. It was lightweight, rain-proof and compact. And yet, as if through some sort of sorcery, the bag could still stow all that gear my doppelgänger and I decided to carry — an Olympus OM-D E-M1 with its big, chunky 12–40 f2.8 Pro zoom; a Hasselblad Xpan with its 45mm f3.5 lens; a Ricoh GR, complete with its 21mm conversion lens; an Olympus Pen EE–2; a big sack of film; an iPhone; an iPad; chargers; snacks; little bits of photo-centric flotsam and jetsam; and the all-important 1-quart Ziplock bag, filled with airline-sanctioned 100ml bottles of assorted liquids.

Although it required hiring a crane to lift the bag and install it onto my back, it was — once properly positioned — quite comfortable.

Outcome

In Part 1 of this article, I discussed my use of film, and my desire to photograph something other than tourism sites. So this article is going to look at Doppelgor’s influence. In particular, I’ll discuss what it was like shooting with a zoom lens (which is something I haven’t used in nearly a decade), plus my experience of having to shoot from a backpack.

Curiously, I never got over my reluctance to use the Olympus 12–40 f2.8 PRO lens. I felt totally uninspired every time it was in my hands — like I was using a scenic-reprographic machine, instead of a camera. Believe me, I’m fully aware this is an entirely psychological disorder, and that there’s no rational reason for this lens to negatively impact my photographic inspiration.

Nor is there any empirical evidence to support my blasé attitude toward this lens. The fact is, it performed perfectly and never once failed to deliver whatever I asked of it. What’s more, it delivered under conditions I wouldn’t dare have forced upon any of my other lenses (or camera bodies, for that matter). It was subjected to gail force winds; driving rain coming off the North Atlantic; pellets of sleet; and bucketloads of snow — and it stood up to all these conditions far better than I did.

The strange truth is that I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend this lens (or the OM-D E-M1) to anybody. It’s a wonderful, practical and adaptable combination that consistently delivers excellent results when none of my other gear will suffice. And maybe that’s the issue: maybe it’s the fact I’ve designated the camera (generally) and the lens (specifically) as “tools to use when all else fails.” I should view these attributes as heroism, not failure. And yet — precisely because neither the camera nor the lens is a prima-donna — I take them both for granted.

So, sheepishly and reluctantly, I must admit that taking the 12–40 f2.8 PRO lens was the right thing to do.

Unlike my apathetic zoom lens experience, the Lowepro Hatchback 16L AW backpack thoroughly surprised me — surpassing my expectations, and even shifting (slightly) my whole negative attitude toward photographic backpacks. While it’s still true that backpacks are best for lugging your gear between locations (rather than shooting out of the bag), I did find a few workarounds.

First, I purchased a Lowepro Dashpoint 30, which is a small auxiliary bag that attaches to one of the shoulder straps on the chest. The Dashpoint was large enough to carry my Ricoh GR and its 21mm conversion lens. It kept the snow and rain at bay, yet the camera was quickly accessible when I needed to grab a shot. Obviously, this isn’t as immediate as having a camera in-hand —but it’s a lot drier, and every bit as quick as grabbing it out of a shoulder bag.

Second, what I first perceived to be the backpack’s biggest weakness turned out to be one of its primary strengths. The Hatchback requires you access camera gear from the surface of the backpack that contacts your back. Traditional backpacks, of course, are accessed from the surface that faces away from you. Lowepro seems to market this as a “security feature,” since it would be nigh impossible for someone to surreptitiously steal gear from your backpack when the point of entry is actually against your back. Initially, I thought this design would make it just that much harder to extract a camera, but it turned out the opposite was true.

Consider a traditional backpack, in which your gear is accessed from the surface of the backpack that faces away from you. Unless you’re traveling with an assistant who can reach into that backpack for you, the only way to get to your gear is to remove the backpack completely, set it down, turn it around, unzip a compartment and extract the gear. But with the Hatchback, I found I could access my gear without removing the backpack! With the waist strap cinched, I would simply shrug the bag off my shoulders — allowing it to fall perpendicular to my body. The compartment that had been facing my back was now facing straight up. Still secured by its waist strap, I would simply rotate the backpack around to my hip, open the camera compartment, and extract the gear. No, it wasn’t as fast or easy as working with a shoulder bag, but it was much faster than extracting gear from a traditional backpack.

While packing for Iceland, I discovered yet another advantage of the Hatchback 16L AW — if I yank all the dividers out of the camera compartment, it becomes just large enough to hold my Domke F–5XB — which is the bag I probably use for 75% of my street work. So, not only did the Hatchback prove itself worthy as a shooting bag (at least as worthy as a backpack can be) but, in the future, it will also serve as a great transport bag — allowing me to transport gear in the backpack, then grab the pre-loaded Domke from inside and commence shooting.

Epilogue

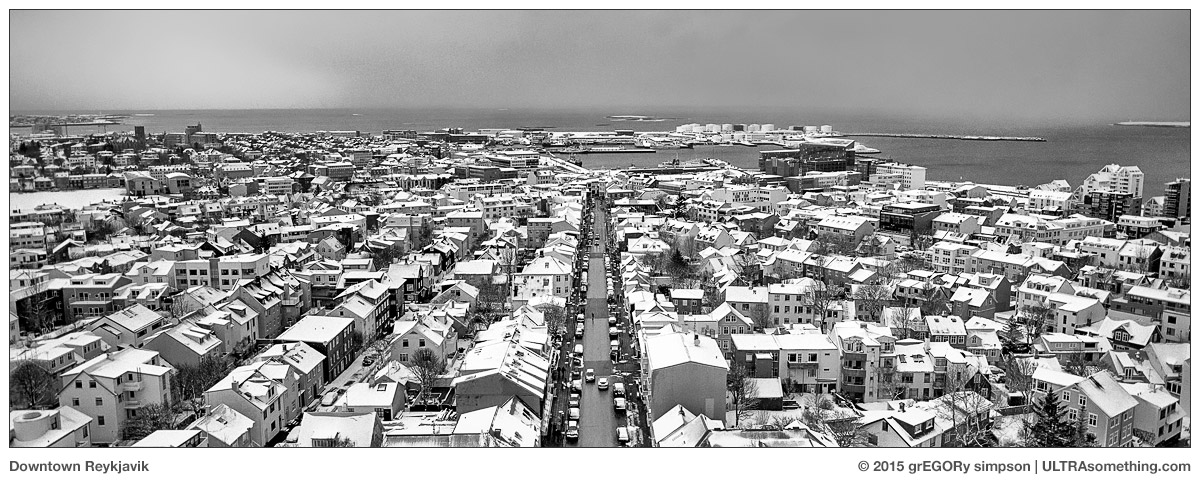

After returning from Iceland, my doppelgänger and I quickly went our separate ways. As usual, he left me with the responsibility of processing his photos and propagating them to all who wish to see them. This was probably a mistake on his part, since I selected some of his least-touristy shots to share.

I have no idea when I’ll see him next, nor do I really care. But it’s nice to know we can get along when we have to. Hopefully, the next time we’re forced to travel together, we’ll be able to employ the whole “two Leicas and a couple of lenses in a Domke F–5XB” strategy. It would be so much less involved.

©2015 grEGORy simpson

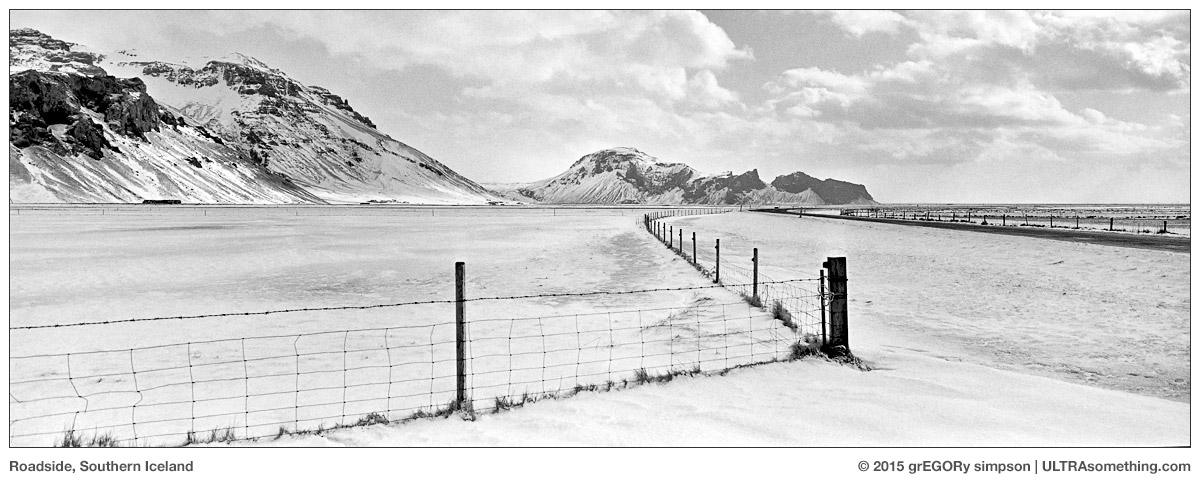

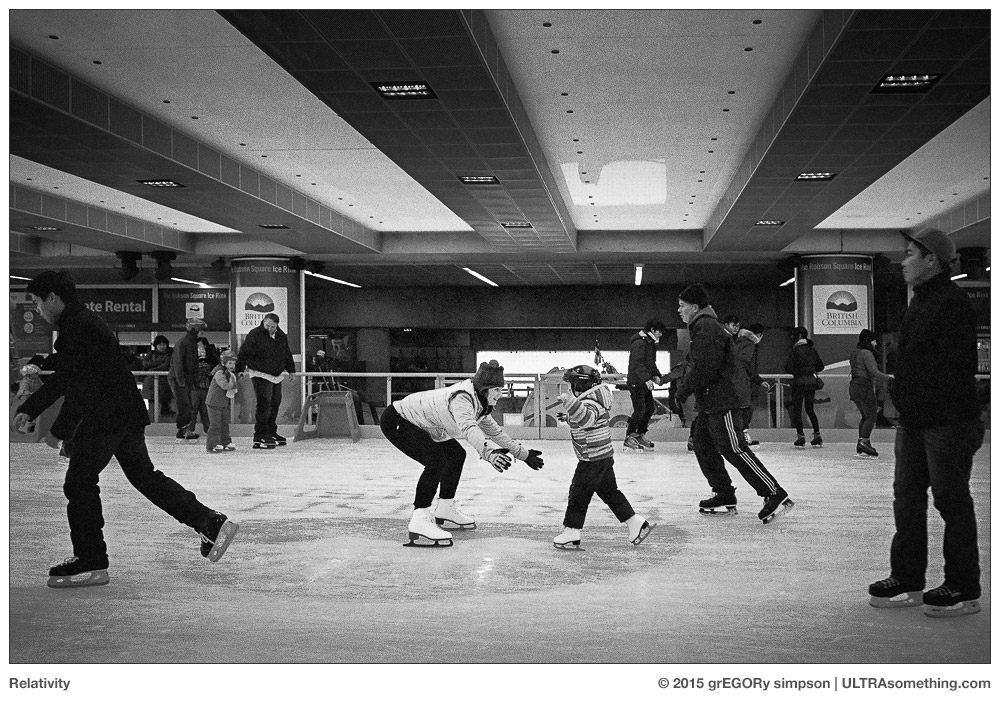

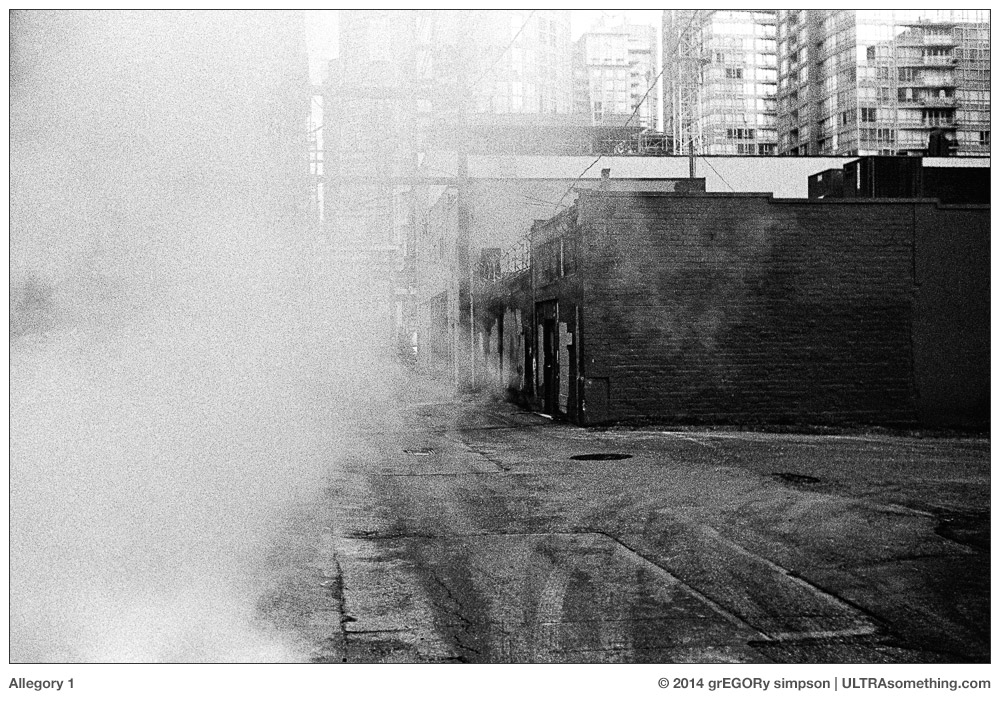

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: In direct contrast to the photos accompanying the first article, these are all products of the digital paraphernalia that Doppelgor and I carted to Iceland.

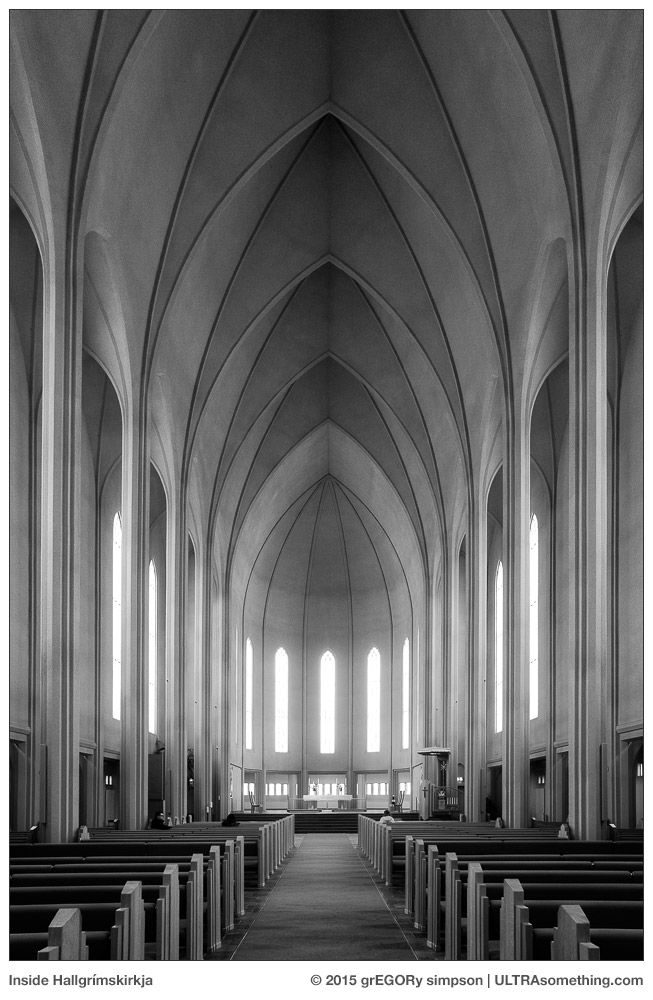

“Reynisfjara Beach” was shot with the Olympus OM‑D E‑M1 and the Olympus M. Zuiko 12‑40 f2.8 PRO lens. This is one of Iceland’s most extensively photographed beaches, made famous by its jagged, off-shore rock formations and the massive, crystallized basalt columns that line its cliffs (and inspired the design of Hallgrimskirkja) — none of which you see here. Sure, I photographed all those things, but you can see that stuff all over the internet. This is the shot that, for me, feels most like being there on that day, and at that time. At least the beach’s other claim to fame — its black sand — managed to make an appearance in the frame.

“Defiance” was taken in Hólavallagarður Cemetery, and comes courtesy of the little Ricoh GR. I seem to be drawn to anything with a crypt, vault, tomb, ossuary, graveyard or columbarium. I’m not sure why I enjoy them so much? Maybe it’s because I won’t have the opportunity once I’m interred in one.

“Vik: 5 Minutes Earlier.” Five minutes before I took the previously discussed shot, the scene looked like this one. For the sake of documentary completeness, I thought it might be nice to show there’s actually a gigantic mountain looming behind that little church. A common cliché, repeated all around the world, is “if you don’t like the weather here, wait 5 minutes.” I can assure you, Iceland is the only place where this hackneyed old phrase actually applies. When I took this shot, the weather had just turned so nice that I was kicking myself for carrying the Olympus OM‑D E‑M1 and its 12‑40 f2.8 PRO lens. “I should have grabbed the Xpan,” I thought. 5 minutes later, big goopy blobs of slushy snow were dripping from the camera. That’s Iceland.

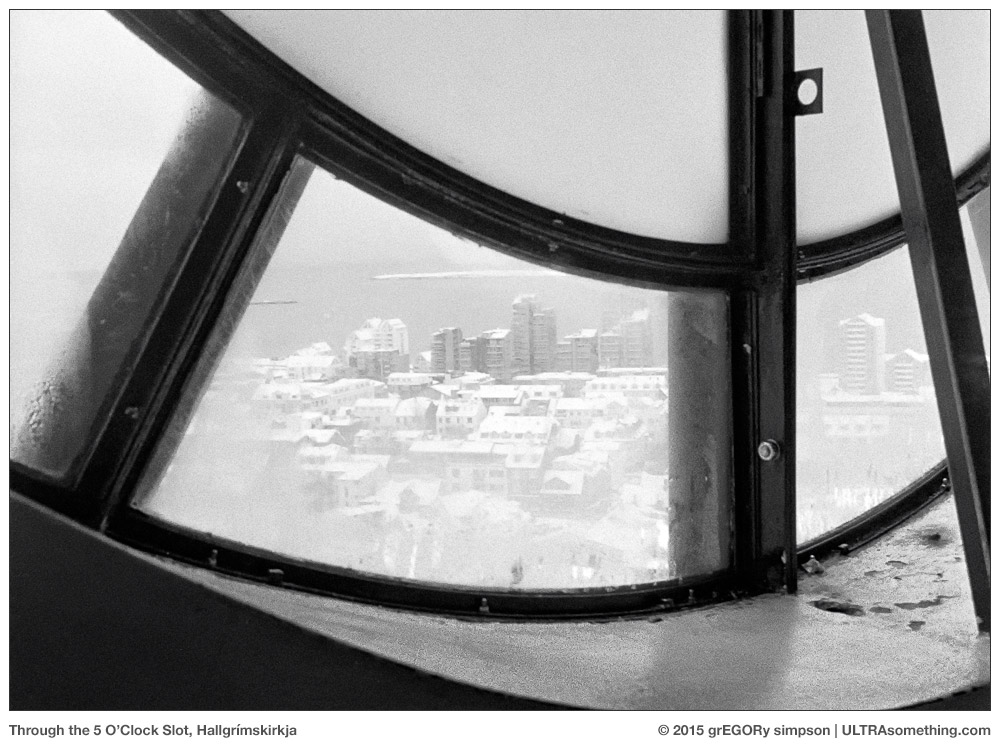

“Inside Hallgrimskirkja” provides proof positive why it’s always a good idea to have a 21mm lens in your pocket. Even if, as in this case, it was only a 21mm conversion lens for my little Ricoh GR.

“Squall, Southern Iceland” illustrates a beach that I suspect might be a popular destination in the summer. This, obviously, was not summer. Score another victory for the weather-sealed Olympus OM‑D E‑M1 and the 12‑40 f2.8 PRO lens.

“The Isolation Myth” is a shot of Mýrdalsjökull Glacier (and a few of its visitors) taken (of course) with the OM‑D/12‑40 f2.8 PRO combo.

“A Crack in the Sky” is about as rigid an interpretation of the first Yin Every Yang article as is possible. Directly behind me is Skógafoss waterfall — its frozen mist tickling the back of my neck. Between me and the waterfall are roughly 100 tourists setting up tripods — all jockeying for the clearest, tourist-free view of the waterfall; all probably sitting at home right this minute using Photoshop to clone one another out of the photo. Me? I watched the chaos, took a few photos to document it, then turned 180 degrees and shot the illusion of desolation everyone else was trying so hard to create in front of the waterfall. As you would expect, it’s the Olympus OM‑D E‑M1 and the Olympus M. Zuiko 12‑40 f2.8 PRO lens crunching the numbers and recording them to SD card.

“Obligatory” is the sort of typical Icelandic shot one expects to see when subjected to someone’s Icelandic vacation photos. I’m rather embarrassed to include it, but I felt a bit sorry for taking advantage of Doppelgor — he doesn’t read this blog, and I’m rather certain he wouldn’t be very happy with the photos I selected to show. So, just for him (and because we have to share a body), I uploaded this shot of Seljalandsfoss Waterfall. It was taken near dusk, and in a driving snow storm. Doppelgor fashioned a makeshift tripod out of a quickly mounting pile of snow, plopped the Olympus OM‑D E‑M1 into the middle of it, set the shutter speed to 1/15s, and took this little bit of stereotypical insipidness.

“Occasus Borealis” (shown below) is definitely ugly enough to require a bit of explanation. Doppelgor wanted to go and photograph the Northern Lights — as if the hundreds of thousands of online photos weren’t plenty enough. Knowing it would be pitch black, and that we’d probably be shooting exposures well in excess of 15 seconds, he actually wanted us to bring a tripod. I talked him out of it. “Lean the camera up against a post or the side of a bus or something,” I said. He wasn’t pleased, but given the tight size and weight constraints of our carry-on luggage, he decided he’d rather have pants than a tripod. We stood outside in the middle of the night, in the middle of nowhere (apologies to the residents of Thingvellir), and waited hours for the spectacle that never came. Two months later, I’m just now regaining feeling in my toes. Doppelgor got rather bummed out that night, and went back to the bus to warm up. So I borrowed his OM‑D, jammed the side of it up against a signpost, and took this photo of the missing lights. I decided, since everyone posts photos of their Northern Lights successes, I should document what failure looks like.

Speaking of failure, that’s exactly what I consider this particular photo collection to be. There is really nothing of myself in these photos. In spite of the fact they (ostensibly) try to avoid the most overtly clichéd attributes of travel photography, they don’t actually express anything. I’d like to blame the zoom lens, but soul does not come from lenses, cameras or anything else you can buy at your local camera shop. It comes from within. And yet, in spite of its inherent soullessness, equipment selection can have a huge impact on one’s photography. If I had left the OM-D and its zoom lens at home, and taken the M2 instead, I have no doubt I would have returned with a far greater selection of soulful photos. Why? Simply because I feel more inspired with a mechanical rangefinder in my hands. Of course, this sort of admission is exactly the type of statement that makes people call me names on photography forums — which is why I decided to bury it down in the “About These Photos” section. I mean, seriously… does anyone actually read anything that follows the “official” end of an article?

FULL DISCLOSURE: The Lowepro backpack discussed in this article was given to me, free of charge, since my local Lowepro rep also happens to be a friend. You’re welcome to believe this might well be the reason why I gave it a favourable review — but I assure you my opinions can not be purchased for a mere US$79 (retail). Actually, they can’t be purchased for any price.

REMINDER: If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.