Bloggers are know-it-alls. I know this because I am a blogger, and thus know it all. Fortunately, most of us limit our didactic soliloquies to a single subject — thus freeing ourselves from the burden of having to explain everything to everyone.

For the ULTRAsomething blog, I’ve chosen to expatiate on photography. Regrettably, I long ago opted to avoid the lucrative sub-genre of “better photography through trendy gear acquisition,” and instead chose to spray my verbiage in the general direction of “better photography through existentialism, nihilism, philosophy and psychology.”

Naturally, being a know-it-all, I was fully conscious of this avenue’s inevitable unpopularity — but I also knew that introspection is far more likely to improve one’s photography than replacing last month’s gear with this month’s.

The upside of such unfashionable pontification is that I basically have the niche all to myself. This means I can invent whatever theories I want, and thanks to the worldwide reach of the internet, they soon become uncontested fact.

Usually I present my hypotheses within tidy little essays that both formulate and justify whatever crap is currently rattling around in my head. But my latest bout of psychological pondering has me stumped. Even though I make it all up as I go, I still want my theories to possess a modicum of plausibility. But, try as I might, I can find no cogent answer to the following question:

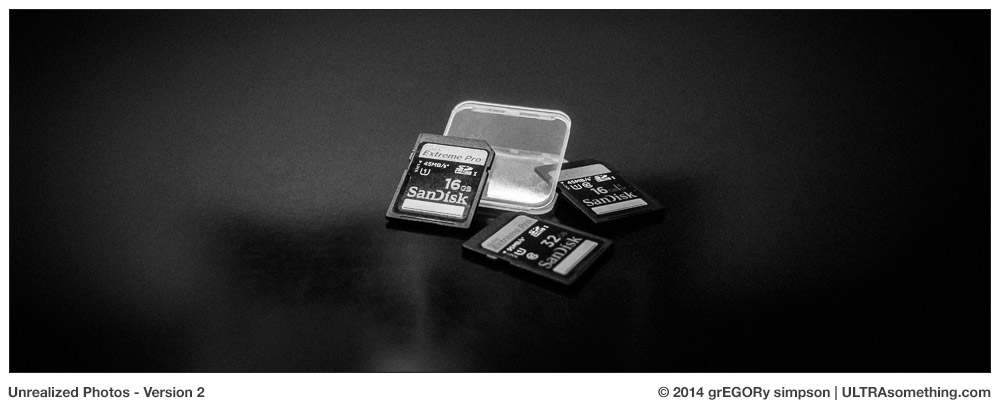

“Why, when I see the following stack of objects atop my desk, am I filled with excitement, anticipation and hope…

… while the similarly-themed stack of objects, shown below, stimulates absolutely zero emotional impact?”

Both photos depict a means to the same end. Both are empty vessels, ready to be loaded into a camera and filled with photographs that have yet to be shot. Shouldn’t they have an identical effect on my psyche?

With the film stash shown here, I’ll be able to shoot roughly 2000 photographs (depending on which cameras I use). The trio of SD cards should hold twice that many photographs (again, depending on which cameras I use). But wait — not only do I own more SD cards than what’s shown here (enough for at least 10,000 raw-format photos), but SD cards can be used time-and-time again, yielding a nearly infinite number of “potential images.”

Based on these statistics, shouldn’t the SD cards stir my photographic passions more than the film? If a big stack of film ignites my expectations for all those yet-unrealized photos, why does a stack of SD cards fill me with no more hope than when I look at a pair of my shoes? I don’t gaze upon my shoes and imagine all the places they’ll take me. And frankly, it would be a little odd if I did. So why do I do this with film?

Some might think it’s because I prefer film to digital. But that’s not the case. I prefer both. Each has its merits and its demerits. Each is indispensable in ways the other is not. I would be no more capable of choosing which to eliminate from my life than would a mother choosing between her children.

I’ve considered tactility as a potential factor. That is, film produces a tactile, physical result — an actual image on a strip of acetate or polyester. The SD card stores data — the opposite of tactility. But in reality, all my film gets digitized and fed into the same Lightroom catalog, where its data becomes indistinguishable from data recorded on an SD card. So that can’t be it.

Perhaps it’s more a matter of longevity? After all, film is “permanent,” while data is fleeting. Once you’ve erased an SD card, your photos are at the mercy of your media backup strategy. But negatives have their own Achilles heel — fire and theft. And unlike digital files, negatives can’t be cloned ad infinitum. Destroy a negative and poof — it’s gone forever. Destroy a digital file and I’ve still got three backups scattered around the world. Since all my film gets digitized, it also gets subjected to the same backup strategy as anything shot with a digital camera. So the only difference is that film gives me one additional “backup” copy — the negative. But having one additional backup is hardly a reason for such a visceral emotional difference.

A decade ago, I thought film was more “future proof” than digital. But do I still? I was always quite aware that anything shot on film could one day be re-scanned and re-processed — using technological improvements in both equipment and software to yield a better print. Yet for some curious reason, I thought this wouldn’t be true with digital. I believed that “all the data in a digital file is already being fed into the computer, so it can never look any better than it looks today.” But this is simply not true. I have digital files taken a decade ago that looked so horrible, I assumed they were destined for obscurity. But when re-interpreted with modern raw converters and re-processed with modern software, photos made from old raw files can also look better now than when I took them. So I no longer believe in the “future proof” theory. Film or digital — squeeze ’em both hard enough and you’ll always get a little extra juice.

Next, I considered the possibility that film provides more variety. Although both the film and digital worlds feature a nearly inexhaustible assortment of cameras and lenses, there seems to be very little variety in digital sensors. Look at any one slice of time, and you’ll see that most of the cameras produced within that slice have nearly identical sensors. Marketing departments might try to convince you otherwise, but the digital camera market basically acts as a single, homogenous entity. So if I go down to the local camera shop and purchase six current-generation cameras, I’ll basically be getting the same sensor tech in six different bodies. But if I purchase six different types of film, I’ll get six very different “looks.”

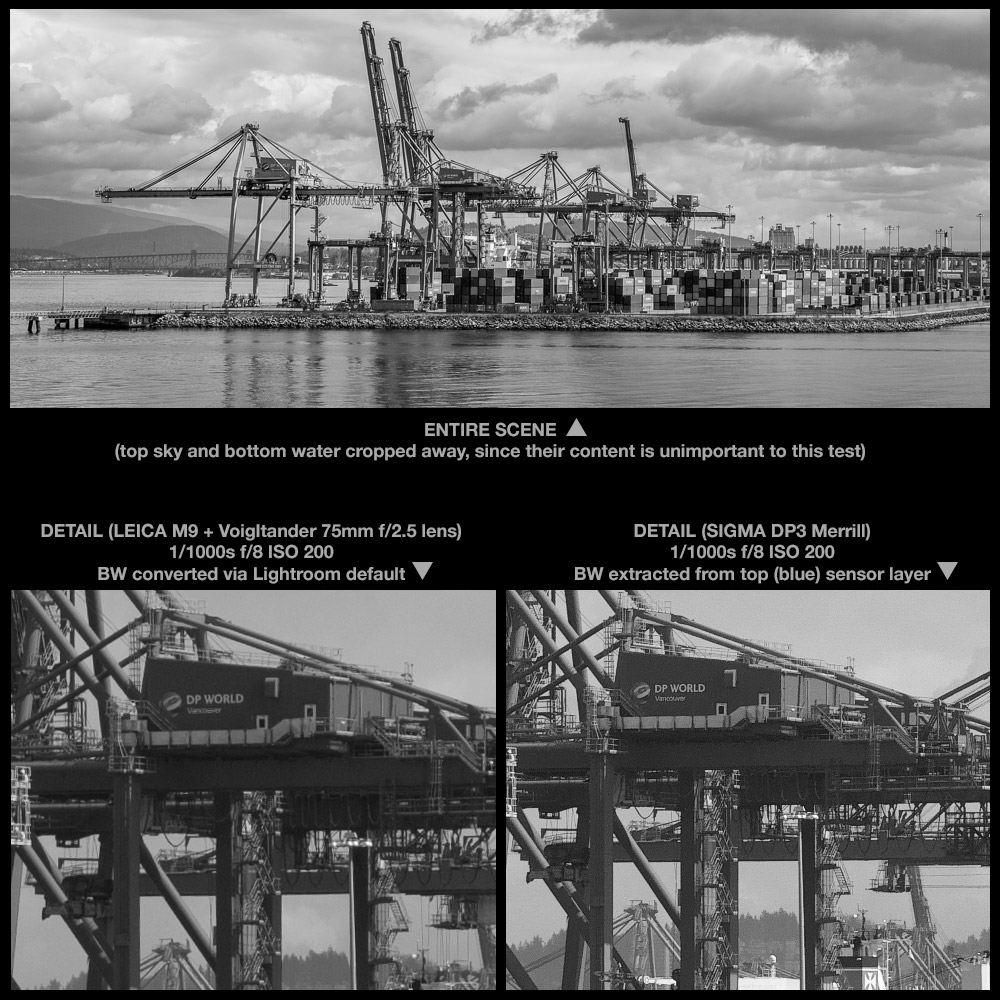

So is that the answer? Is it that film offers more variety? I think not, and here’s the reason: while digital cameras may all be similar to one another at any one time, they continue to change throughout time. Sure, there might be precious little variety if I purchase a bunch of new digital cameras at the same time — but if I purchase different digital cameras at different times and from different eras, I’ll get plenty of variety. Just look at the visible differences produced between, say, a CMOS sensor and a CCD. They’re world’s apart. But they’re both digital. And though they’re the exception, there are a few oddball sensors out there that will also give you a different “look” — Leica’s Monochrom; Sigma’s Foveon; Sony’s upcoming curved sensor; Fuji’s X-Trans (though that one’s more similar to the ubiquitous Bayer pattern sensor than it is different). So the variety is there with digital — you just need to own enough cameras to see it.

Ahh! Maybe that’s it? By shooting film, I can achieve a wide variety of looks within a single camera body. But to achieve a similar diversity with digital requires ownership of multiple bodies. This was likely the same bong from which Ricoh toked back in 2009, when they released their GXR camera. For those who don’t remember, the Ricoh GXR was a camera that featured interchangeable sensors. I thought it was the greatest idea in the world, and I still own and love this camera. Unfortunately for Ricoh, not a lot of other people agreed. Consequently, I can no longer buy new sensors for my GXR, making it the digital equivalent of Kodak’s equally irrelevant APS film format.

So is that it? Is frugality the answer? It’s certainly cheaper to buy multiple types of film than multiple types of digital cameras. And if I owned only one film camera, then I might have just solved this case. But I don’t. I actually own far more film cameras than digital cameras. So the notion that film lets me achieve multiple looks with one camera, while digital requires multiple cameras completely disintegrates between the theory stage and reality.

So what is it? Why do I perform an excited little dance whenever a fresh batch of new film hits ULTRAsomething headquarters? Yet a new SD card thrills me slightly less than a new tube of toothpaste?

I haven’t a clue. But I’m determined to figure it out. It is, after all, why they call it PSYCHO-logy.

©2014 grEGORy simpson

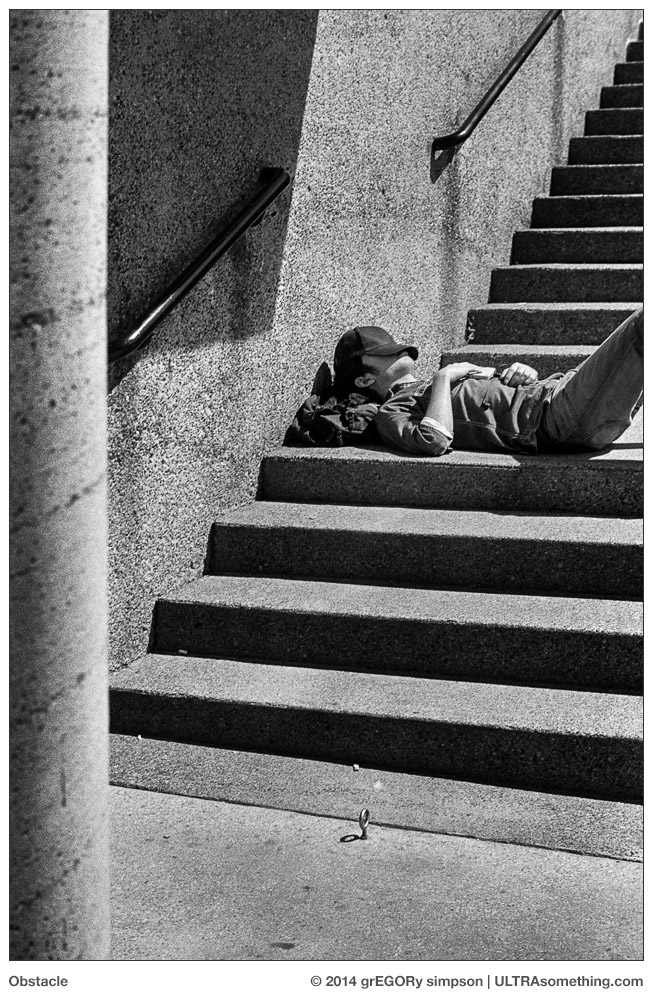

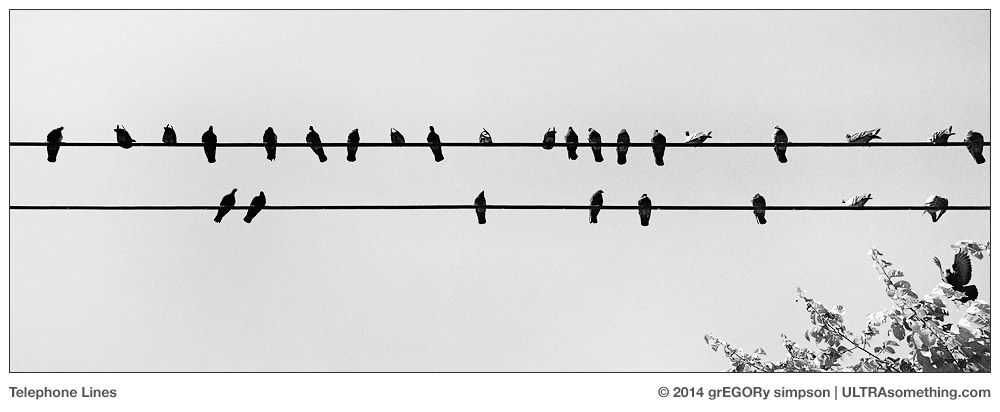

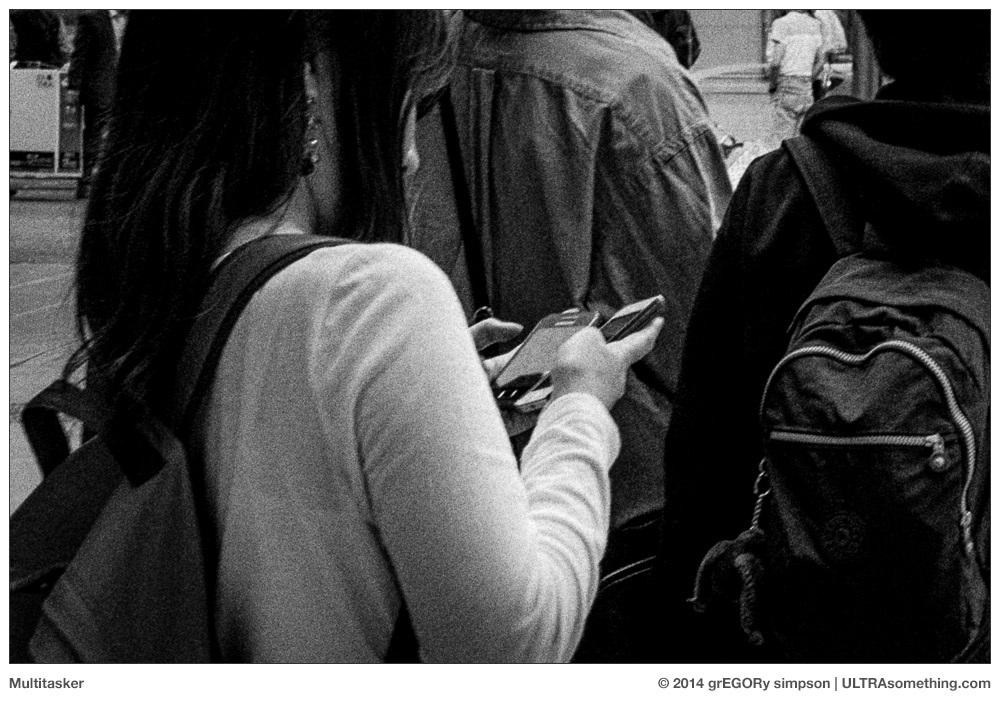

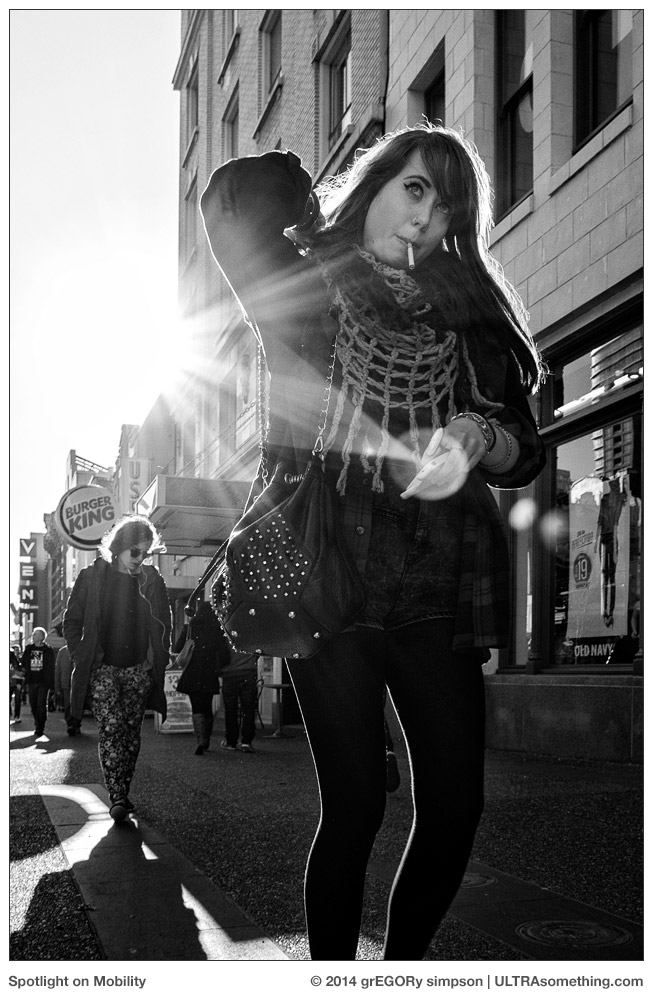

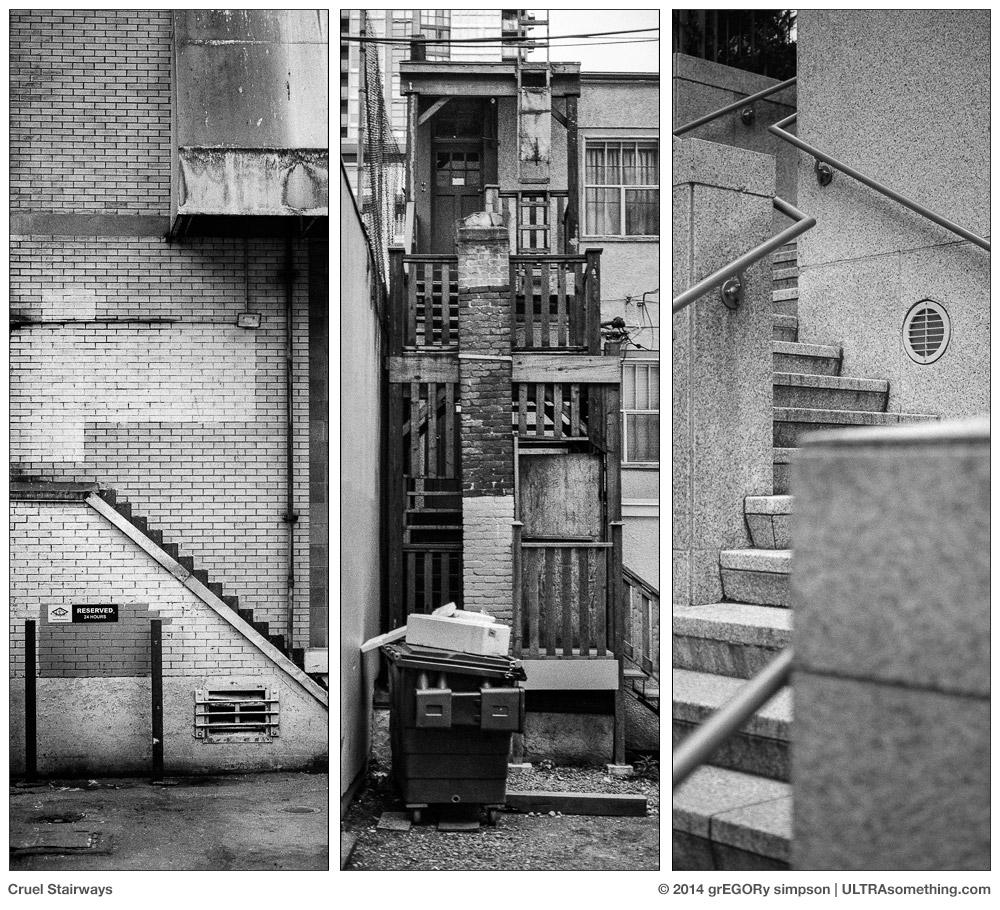

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS:

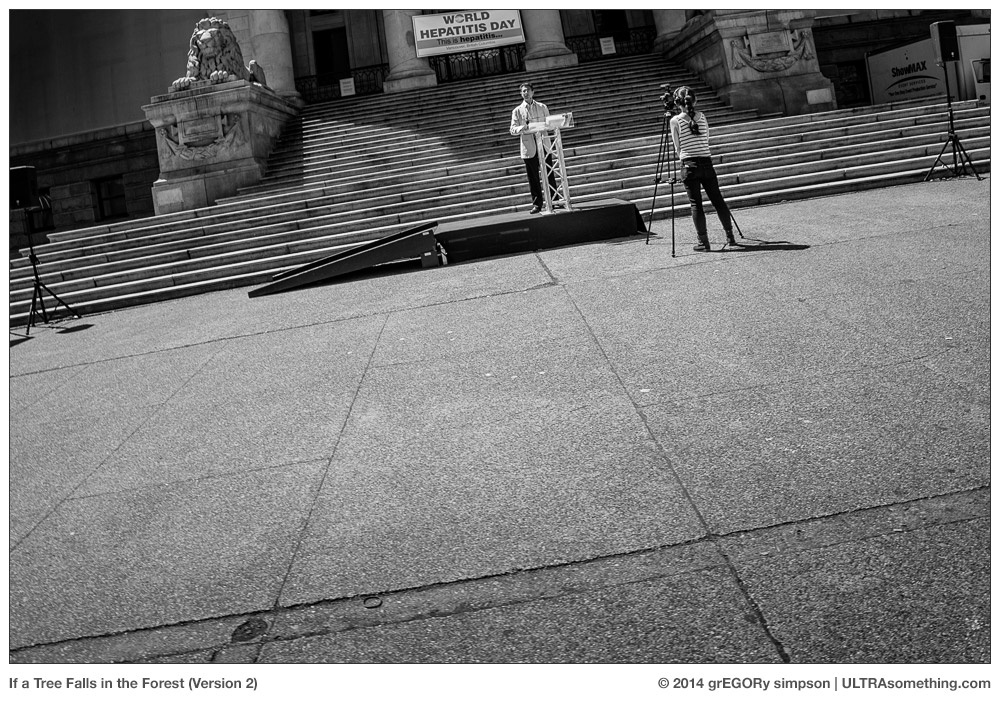

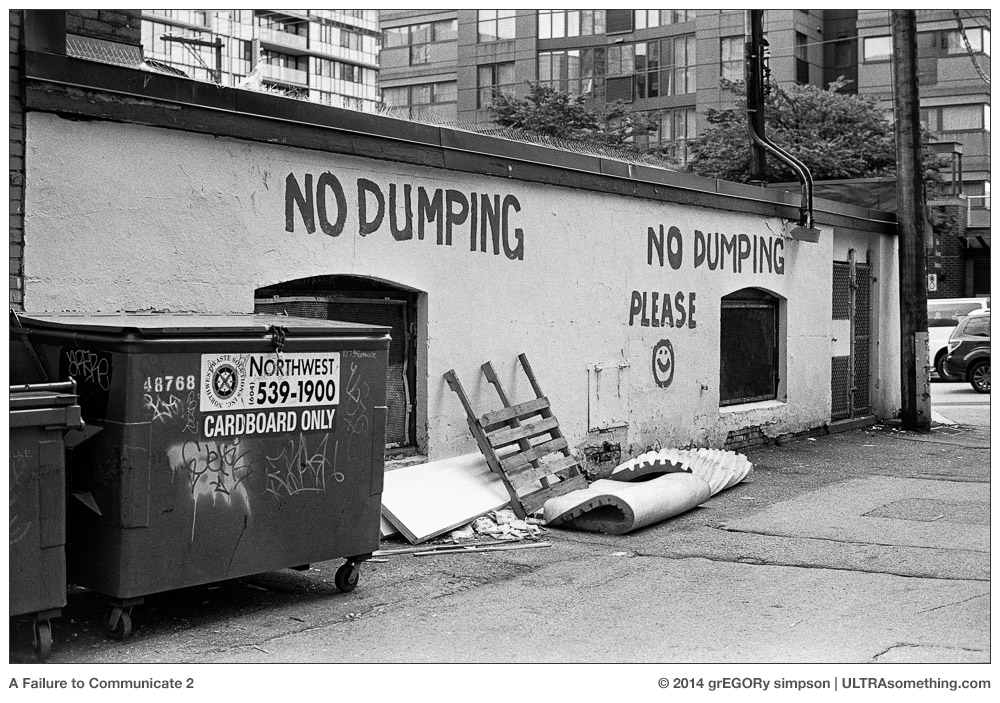

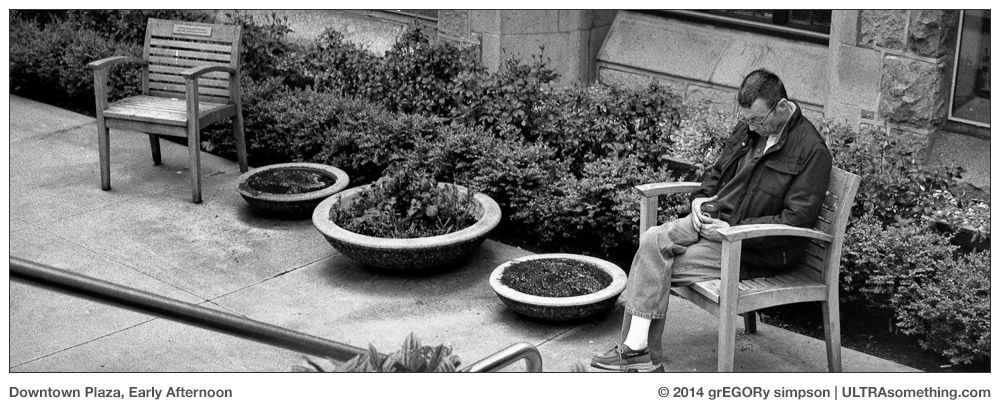

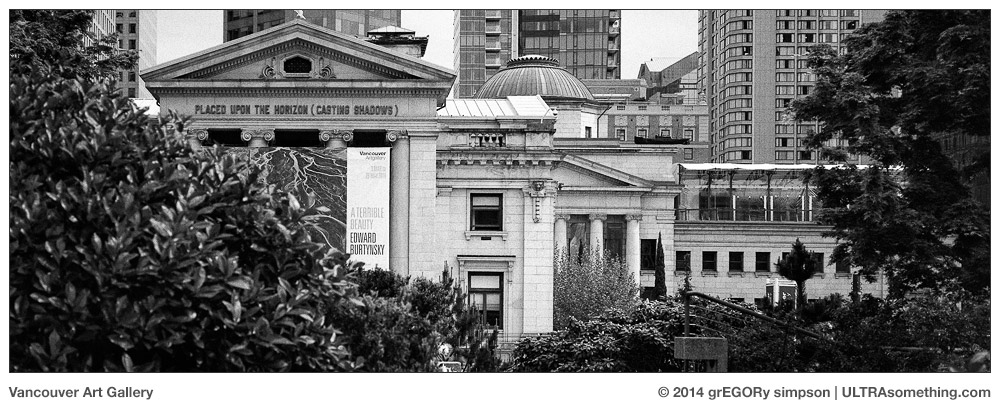

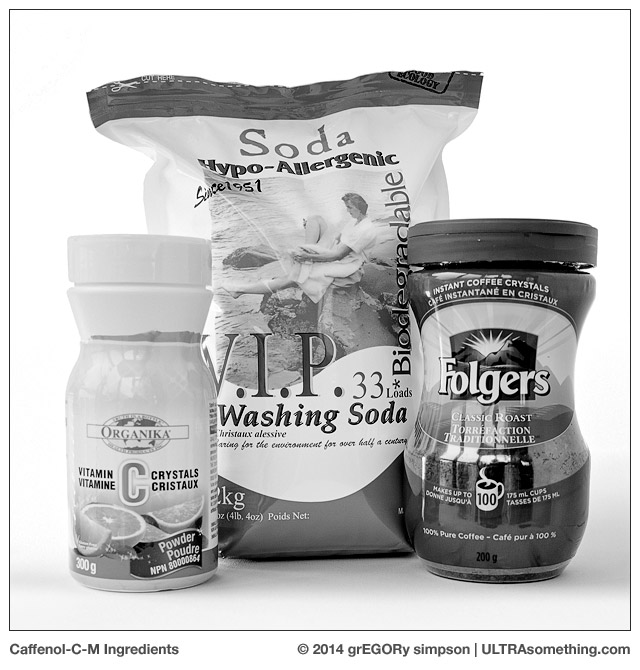

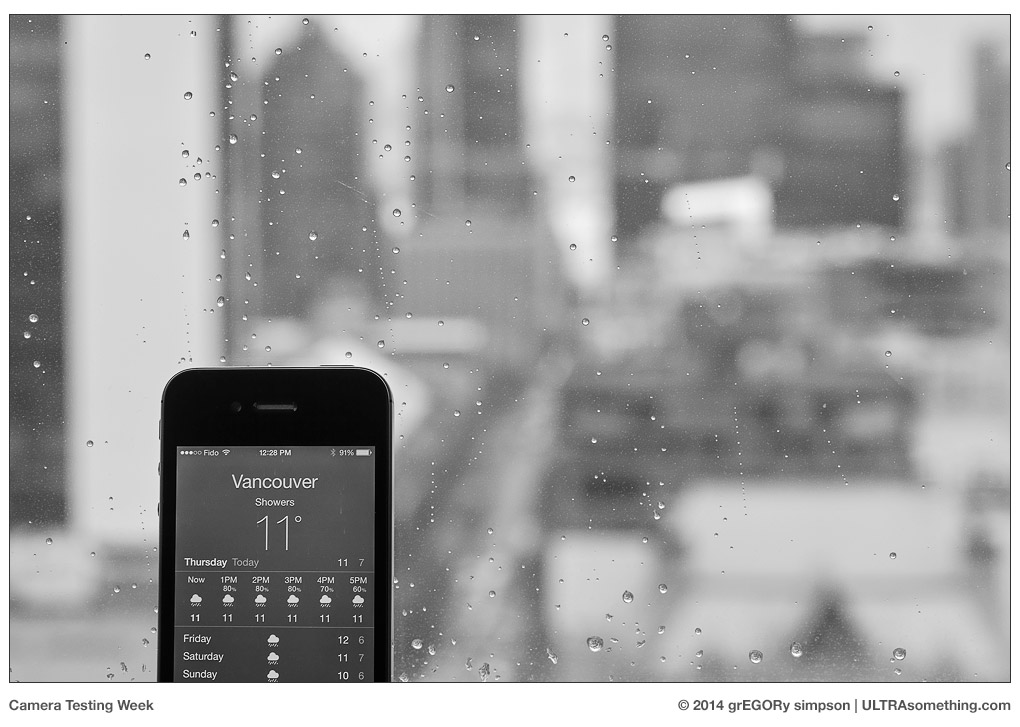

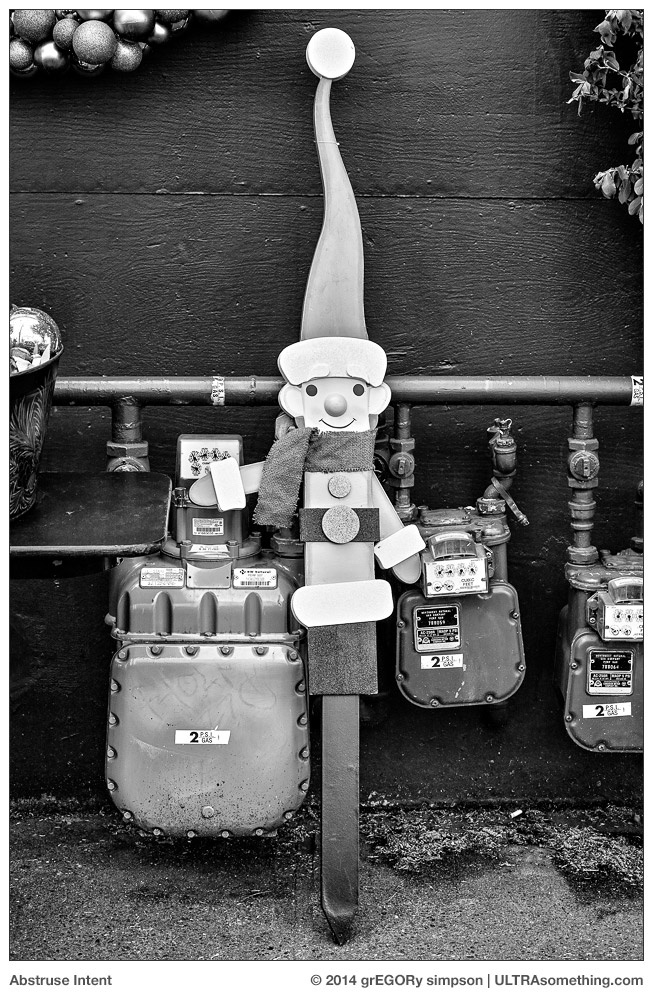

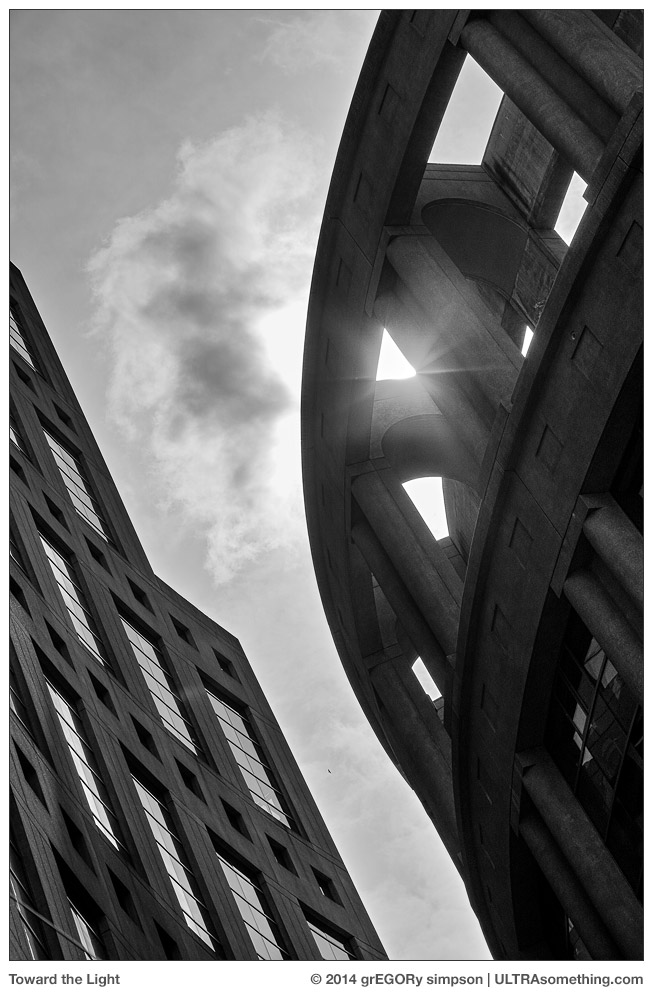

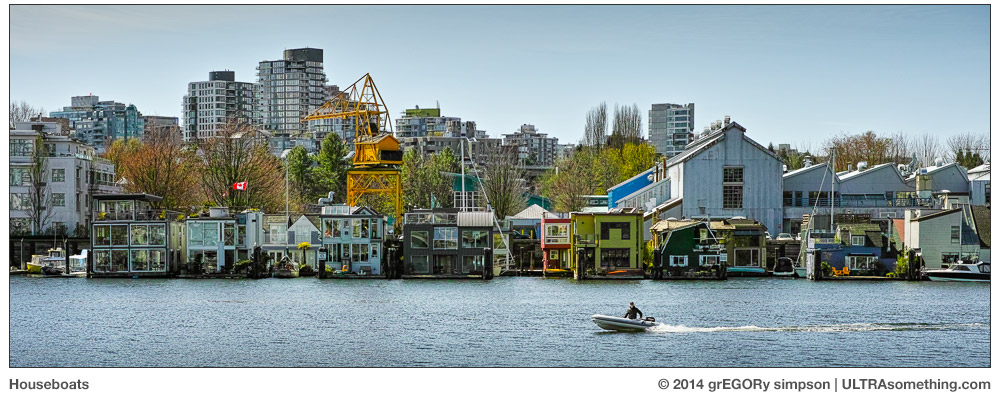

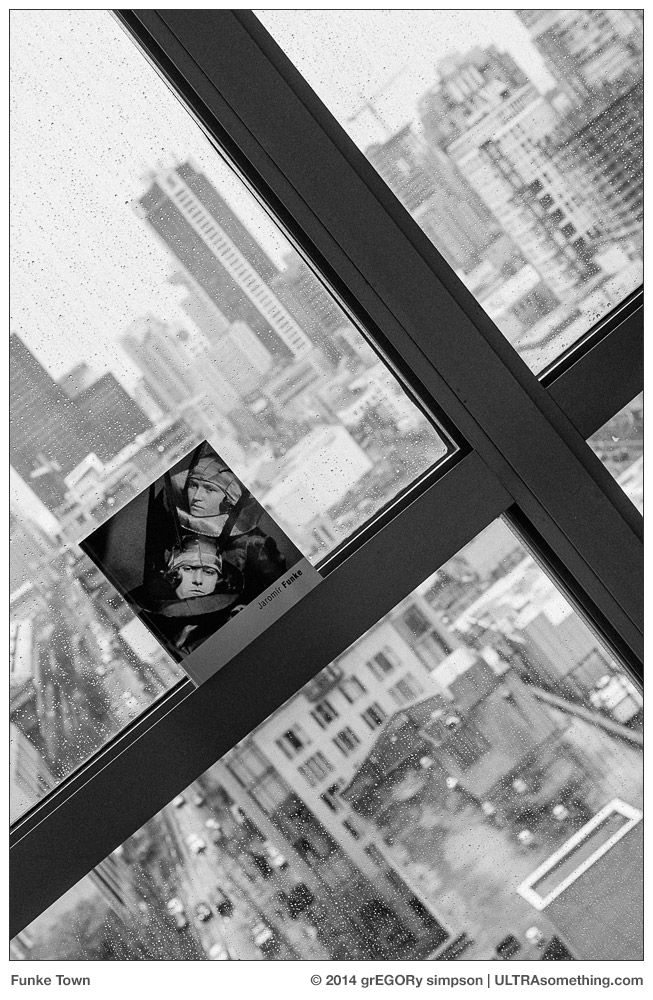

The photos contained within this article shine no additional light on the conundrum. Rather, they disprove yet another possible theory — that my approach to photography might somehow be different depending on whether I shoot film or digital. But it turns out this isn’t the case — I respond to the same subjects and the same stimuli, whether I’m depositing that image onto film or onto an SD Card. Case in point: the two “If a Tree Falls in the Forest” photos. Both illustrate the same situation — an embarrassingly small turnout to what, obviously, was expected to be a much more significant event. The first photo (which, paradoxically, is “version 2” of the “If a Tree Falls in the Forest” theme) was shot on a Ricoh GR digital camera using its 21mm (equivalent) lens adapter attachment. The second photo (which is “version 1” of the “If a Tree Falls in the Forest” theme) was shot with a Hasselblad Xpan using its 45mm lens, and developed in Caffenol-C-M. (See Note 1)

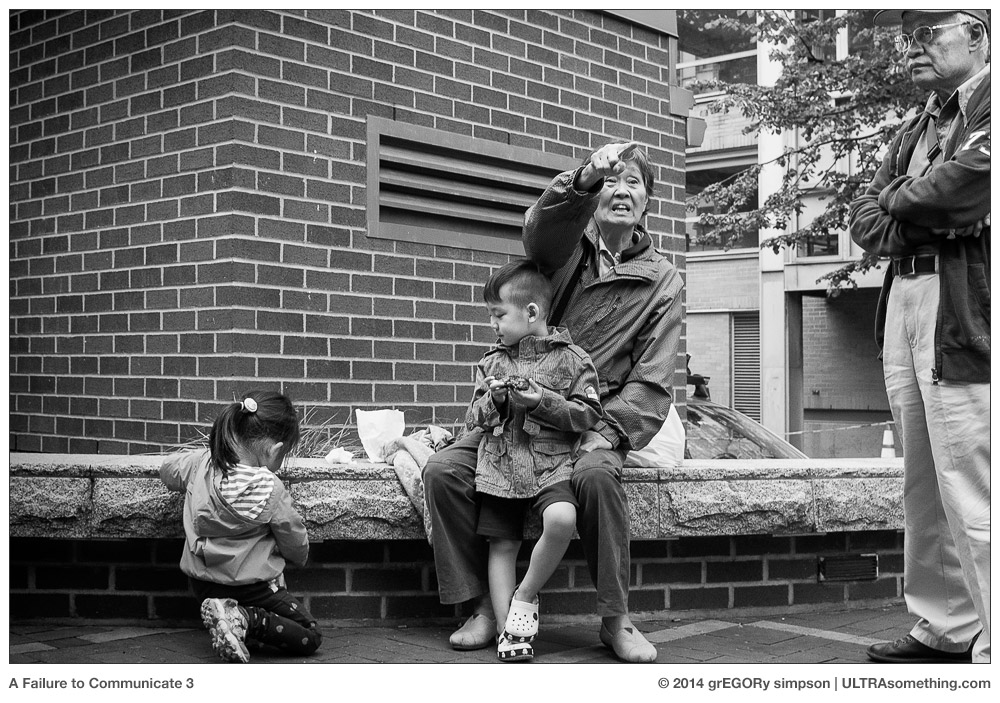

“A Failure to Communicate 3” is a continuation of a theme that began in my previous article, The Blacksmith’s Lot. That article contains two different photos illustrating a communications breakdown — both of which were shot on film. But the photo contained within this article was shot on a digital Ricoh GR, this time with its unmodified 28mm (equivalent) lens. Just as with the “tree falls” series, it illustrates that film and digital seem to have no bearing on the sort of photos I take, eliminating this as another potential answer to the question posed within the article.

Note 1: For those wondering why this photo was taken with an Xpan, yet isn’t panoramic, the answer is simple: The Xpan lets you choose between panoramic (65 x 24) format or standard (36 x 24) format. What’s particularly cool about this is that you can make these changes mid-roll. I learned rather early on that I can always squeeze one extra frame out of a panoramic roll of shots if, at some point in the roll, I switch the camera over and take one standard frame image. It’s the sort of thing you do to maximize your film dollar, and is also the sort of thing that’s completely unnecessary when shooting on SD cards — thus making yet another effective argument that my emotional delight at having plenty of unexposed film in stock is, perhaps, a bit psychotic.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.