Simplistic armchair psychologist that I am, I believe that most everyone’s personality — no matter how nuanced or complex — can ultimately be defined and thus predicted through a series of basic either/or questions. Are you a dog person or a cat person? A coffee drinker or a tea aficionado? Mac or PC? Give us humans a choice, and we’ll likely have a pronounced preference. Give us humans enough choices, and our entire personality is revealed.

Simplistic armchair psychologist that I am, I believe that most everyone’s personality — no matter how nuanced or complex — can ultimately be defined and thus predicted through a series of basic either/or questions. Are you a dog person or a cat person? A coffee drinker or a tea aficionado? Mac or PC? Give us humans a choice, and we’ll likely have a pronounced preference. Give us humans enough choices, and our entire personality is revealed.

It’s a bit like a trip to the optometrist — by asking whether you prefer the view through lens “A” or the view through lens “B,” the technician hones in on a prescription tailored just for you.

I like to think that a similar tactic works for photography — follow a line of carefully considered either/or questions, and you’ll arrive at your personal photographic core. Once there, you’ll possess the knowledge to not only decide which camera and lenses to purchase, but you’ll even know what you should photograph with them!

However, as anyone who’s taken a company-sponsored personality test will tell you, the results can only be as accurate as the questions. Ask a stupid question and… well… you know the rest. Most personality tests, I believe, are too flat. Rather than tailoring each question to how the previous one was answered, everyone simply answers the same set of questions — many of which seem more indicative of the test author’s personality than the subject’s.

My test, which I hope to submit to the little-known and highly-clandestine International League of Enlightened Photographers, would involve more “funnelling” — with each block of questions dependent upon how one responded to the previous block. Obviously, with such a technique, the first question becomes key.

And it was only recently that I finally determined what that opening question should be:

“Question 1: Is it the destination or the journey?”

Curiously, it was my approach to using and enjoying two thoroughly modern, yet completely different digital cameras that lead to this epiphany.

Olympus OM-D E-M1

A few years ago, after realizing that the industry had changed and that people were increasingly unwilling to pay (or, at least to pay me) for shots, I ditched all my SLRs — focusing on the sort of photography that I preferred and enjoyed. As a consequence, my big bag-o-camera-tricks has been missing quite a few tools for quite a few years. It’s been without long lenses, macro lenses, shift lenses, fisheye lenses, auto-focus lenses, and lenses adapted from other camera systems. It’s also been without many of today’s so-called “necessities” like video, wi-fi connectivity, rapid frame rates, art filters, multiple exposures, in-body HDR, image stabilization, and super high ISO speeds.

It struck me as somewhat absurd that everybody and their Aunt Bertha had access to all these basic photo capabilities and yet I, a man who defines himself substantially through photography, did not.

And so I searched for what would likely become, for lack of a better term, my “Swiss Army Camera.” It would be the camera to restock my capabilities cabinet, but it wouldn’t necessarily be my “go to” camera for the soul-defining projects.

And so I searched for what would likely become, for lack of a better term, my “Swiss Army Camera.” It would be the camera to restock my capabilities cabinet, but it wouldn’t necessarily be my “go to” camera for the soul-defining projects.

And it was precisely for this purpose that I purchased an Olympus OM-D E-M1.

Over the last few months, many eagle-eyed readers have spotted a smattering of Olympus digital shots in some of my posts, and I’ve received dozens of emails asking that I write a review of the camera. It’s a reasonable request. After all, nearly every photo-related website and publication awarded the OM-D their “Camera of the Year” honor for 2013. And while it’s flattering that, with all this existing evidence, some people still want to know my take on the camera, what can I possibly say that hasn’t already been said? The bottom line is this: the camera functions much like a modern digital SLR (in spite of the fact it isn’t actually one), and it does everything that any reasonable person would expect it to do, and it does it reasonably well.

Frankly, it’s the most boring camera I’ve ever used in my life.

Hmmm, maybe I do have something “new” to add to this discussion, after all.

Mind you, “boring” does not mean “bad.” Some of the least boring cameras I’ve ever used are actually the most infuriating — persnickety film transports, light leaks, sticky shutters. Unpredictability is rarely boring, but that doesn’t mean it’s something we necessarily desire in a camera. The Olympus simply works and works well. Like I said, “boring.”

“Boring” also describes the photos I find myself pulling off the Olympus’ SD card. Since we all know that “it’s the photographer, not the camera,” I’ll be the first to state that the reason my photos from the EM-1 are “boring” is entirely because of me. This is a camera that would excel at photographing your friends at a party, or a lion on safari. It’d be great for scenic vistas at a National Park, or for architectural details in a medieval city. It would effortlessly capture all the action at the local hockey arena, or a bunch of kids running wild at a family reunion. In other words, it’s a camera that’s ideally suited for subjects that I don’t photograph very often or very well. But that’s the point of having a Swiss Army Camera, isn’t it? It’s about having access to a whole set of photographic tools you might not always need, but never know when you might want. Frankly, “boring” is probably a step-up from what usually occurs when I step outside my photographic comfort zone.

I’ve come to think of the OM-D EM-1 as my “destination” camera. It’s the camera I might pull out of the bag when I get to where I’m going; the camera I’ll use to take a photo to commemorate a trip, event or special moment. Of course, I don’t tend to commemorate trips, events or special moments. That’s just not the sort of photography that interests me. I might even go so far as to say that it “bores” me, which is probably a third reason why I declared this “the most boring camera I’ve ever used in my life.” It actually encourages me to go ahead and take all the sort of photos I wouldn’t normally have any interest in taking.

Photographically, I’m much more interested in the “journey.” I’m interested in the jumble of life that happens all around me while I’m simply getting to somewhere else. For this, I need something less “Swiss Army” and far more specialized…

Ricoh GR

I’ve shot it for only a little over a week, but I already feel completely familiar with the new Ricoh GR. It’s not the sort of camera line that reinvents itself with each new product freshening, because the original designers pretty much nailed it on the first try.

One of the many things I love about Leica’s M-series cameras is that, once you’ve owned one, you can pick up any model in its 60-year lineage — film or digital — and you’re immediately acclimated. The same is true of the Ricoh GR. Whether you owned one of the original Ricoh GR film series cameras, one of the earlier GRD digital models, or the GXR (like I do), the ergonomics, handling and philosophy are the same.

Also akin to the M-series Leica cameras, Ricoh GRs have a way of “cutting the crap,” and getting right to the point of photography — particularly if the point of your photography is “the journey.”

Also akin to the M-series Leica cameras, Ricoh GRs have a way of “cutting the crap,” and getting right to the point of photography — particularly if the point of your photography is “the journey.”

Slim enough to fit into the front pocket of my jeans (with me actually in them), it sports a lens with a 28mm equivalent field of view — my ideal focal length for photographing whatever life throws my way. Elegant in function and austere in appearance, the Ricoh GR puts every control directly where my fingers expect to find it. Furthermore, Ricoh allows even the most obsessive photographer to assign these controls to match their needs precisely. I know people claim the Olympus OM-D EM-1 features a similarly rich amount of customization, and compared to its competition (dSLRs), this might be true — but compared to the Ricoh, it’s not even in the same league. I can completely change functionality on the Ricoh, using only one-hand, in the time it takes to bring the camera to my eye. And yes, I bring the camera to my eye because I can’t stand to frame photos with rear-panel LCDs. So my GR has a tiny Voigtlander 28mm optical viewfinder on top.

Most of the time, I’m scale-focusing using Ricoh’s fabulous “snap focus” mode. It’s a bit like using the distance scale to focus an old-school manual lens, except you don’t need to employ a second hand to change the focus distance with the Ricoh.

In those instances when I do use autofocus, Ricoh was clever enough to put the focus confirmation light up high, near the hotshoe. Since I work with my eye pressed to the optical viewfinder and all camera sounds silenced, it’s a huge benefit to see focus confirmation within my peripheral vision. Now, I know what you’re thinking — you’re thinking, “hotshoe-mounted optical viewfinders don’t display any camera information and they don’t correct for parallax. So even if you use center-point autofocusing, how do you know where the true center of the frame resides? How do you know what, exactly, the camera is focusing on?”

I hate to tell you this, but the answer is the one no one ever likes to hear — because the answer is “practice.” That’s right. Simple, basic, rote practice. I first spent about 30 minutes using the rear LCD to focus on objects at various distances, making note of where those objects appeared in the optical viewfinder. With that knowledge, I then started using the optical viewfinder to guess where I thought the autofocus patch would be. Within a single afternoon, I trained myself to achieve a 100% success rate. It helped that Ricoh was thoughtful enough to center the hotshoe over the lens, so one only needs to practice compensating for vertical parallax.

The latest Ricoh GR has also inherited my favorite feature from my old Pentax K5 — TAv mode. As every photographer (hopefully) knows, there are only three variables that contribute to photographic exposure: Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO (which we used to call “film speed” in the pre-digital days). In the film era, one’s choice of ISO was determined by one’s choice of film, so the camera was responsible for only two of the three exposure variables.

The latest Ricoh GR has also inherited my favorite feature from my old Pentax K5 — TAv mode. As every photographer (hopefully) knows, there are only three variables that contribute to photographic exposure: Aperture, Shutter Speed, and ISO (which we used to call “film speed” in the pre-digital days). In the film era, one’s choice of ISO was determined by one’s choice of film, so the camera was responsible for only two of the three exposure variables.

As cameras became more automated, manufacturers introduced a pair of exposure modes to assist photographers: Av (Aperture priority) mode and Tv (Shutter priority) mode. In Av mode, the photographer sets the desired aperture and the camera selects the appropriate shutter speed. ISO was already pre-determined by the film selection. In Tv mode, the photographer sets the desired shutter speed, and the camera selects the appropriate aperture. Again, ISO was already pre-determed by the film selection.

Simple, right? You give the camera two exposure parameters and it sets the third based on its internal light meter.

So now that modern times are upon us, and the ISO parameter has moved inside the digital camera (since it’s no longer determined by film type), why don’t all digital cameras offer a third ‘priority’ mode — one that lets the photographer set both the shutter speed and the aperture, while letting the camera select the ISO? This is exactly what TAv mode accomplishes.

I know some slick-talking marketing types will tell you that all cameras have this feature, but they don’t. What all cameras have is an “auto-ISO” feature, and most work only in conjunction with either Av or Tv modes. They work by allowing the photographer to specify a range of allowable shutter speeds. If the camera needs to set a shutter speed that falls outside this range, then it will alter the ISO to compensate. This is most definitely not the same thing as saying, “give me f/4 at 1/250 and let the ISO fall where it may.” It might seem like a small point, but when you’re shooting on the street, it’s huge — I need to have control over both depth-of-field and motion-blur. Frankly, I don’t really care about noise — that’s going to be the least important factor in the shot. Ricoh understands this, which is just another reason why I consider the Ricoh GR a true “journey” photographer’s camera.

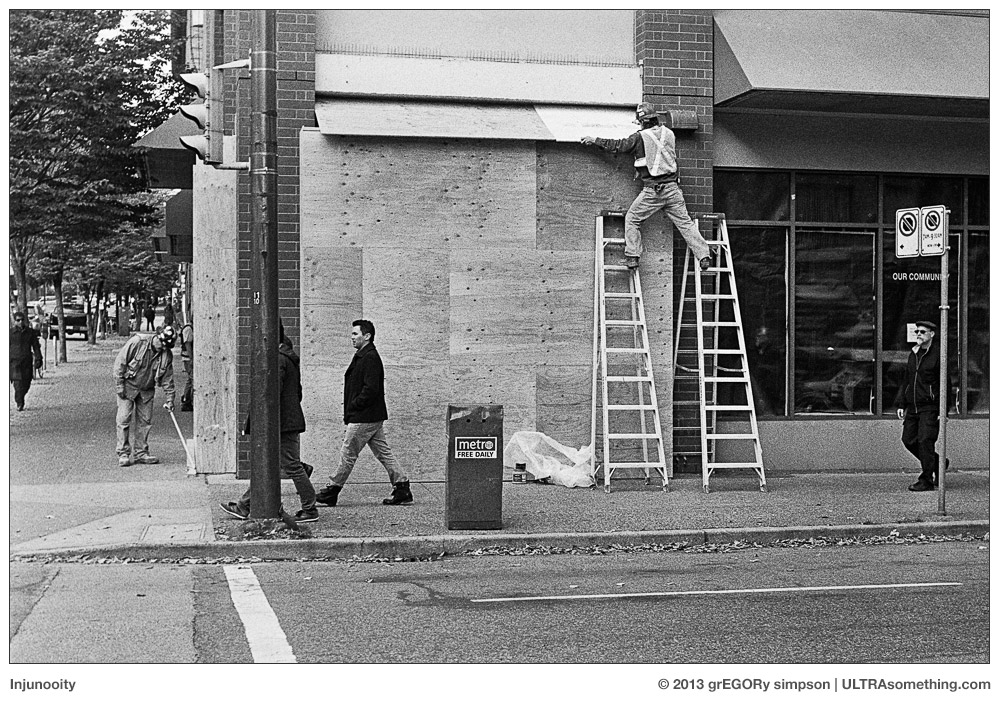

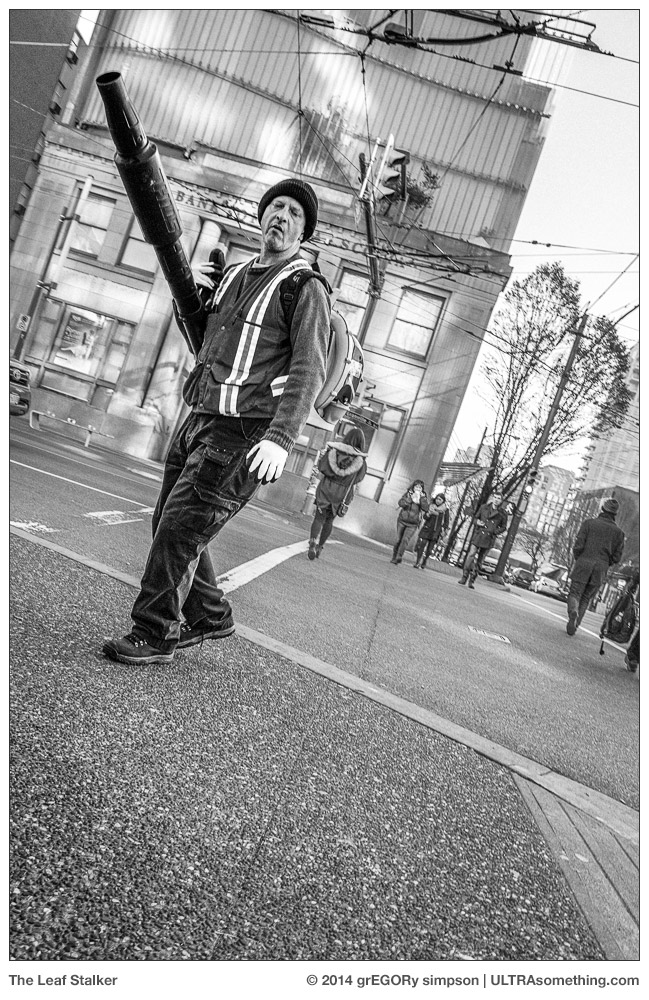

I haven’t even mentioned the stellar image quality, the whisper-quiet leaf shutter, the built-in neutral density filters, or any of a myriad other features that make the Ricoh so incredible. All I really need to say is that, because of its size, performance and responsiveness, the Ricoh GR is a camera that is now always with me, no matter what my destination. Whether I’m going to the grocery store, the dentist, dinner or the ATM, the Ricoh is in my hand. Sure, none of these destinations may be the least bit interesting, but the journey almost always is. And that’s what I like to photograph.

Conclusion

Modern camera developers can build some truly wonderful products when they put their backs into it. Unfortunately, in today’s disposable-minded society, it doesn’t seem to happen as often as it should. Fortunately, both of these cameras fall squarely into the “wonderful” camp. True, they may have been designed for two entirely different types of photographers, but that’s OK — we’re not all one and the same.

So what type of photographer are you? Has your life been a series of places, events and achievements, or has it been a richly textured meandering?

Is it the “destination” or the “journey?”

Whichever way you answer, I’m rather certain I can recommend a camera for you.

©2014 grEGORy simpson

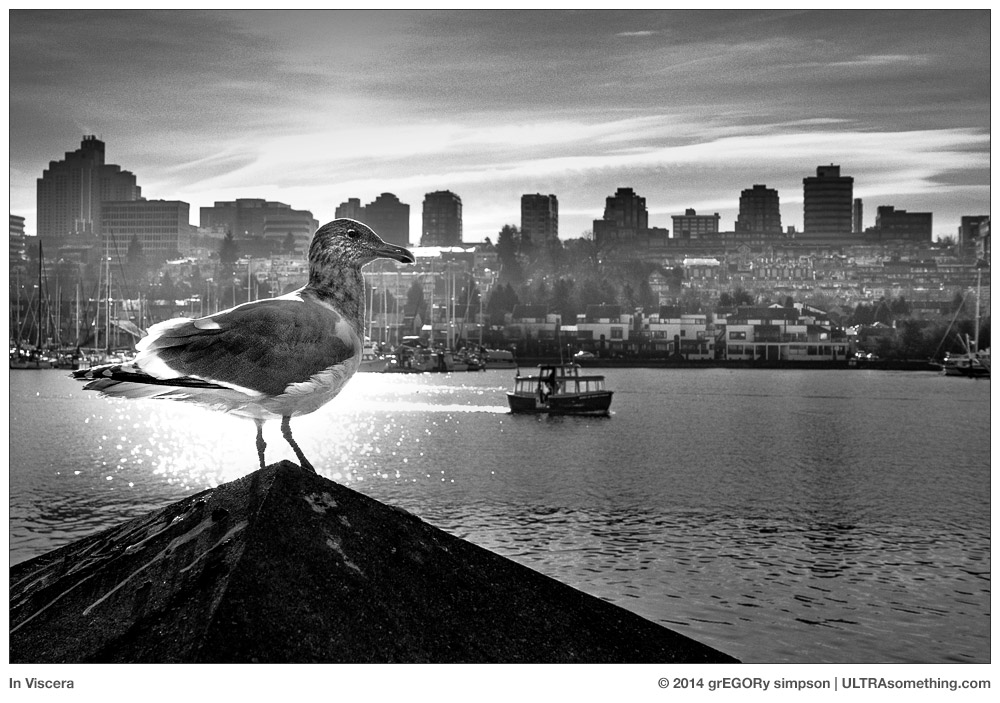

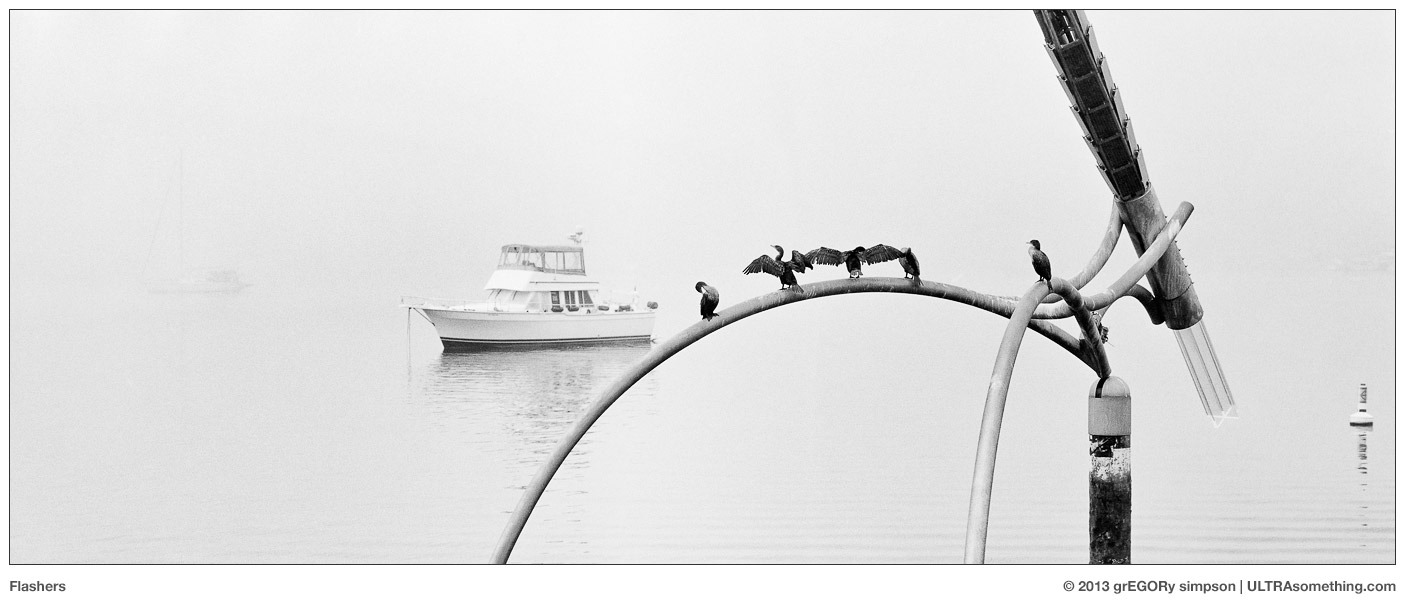

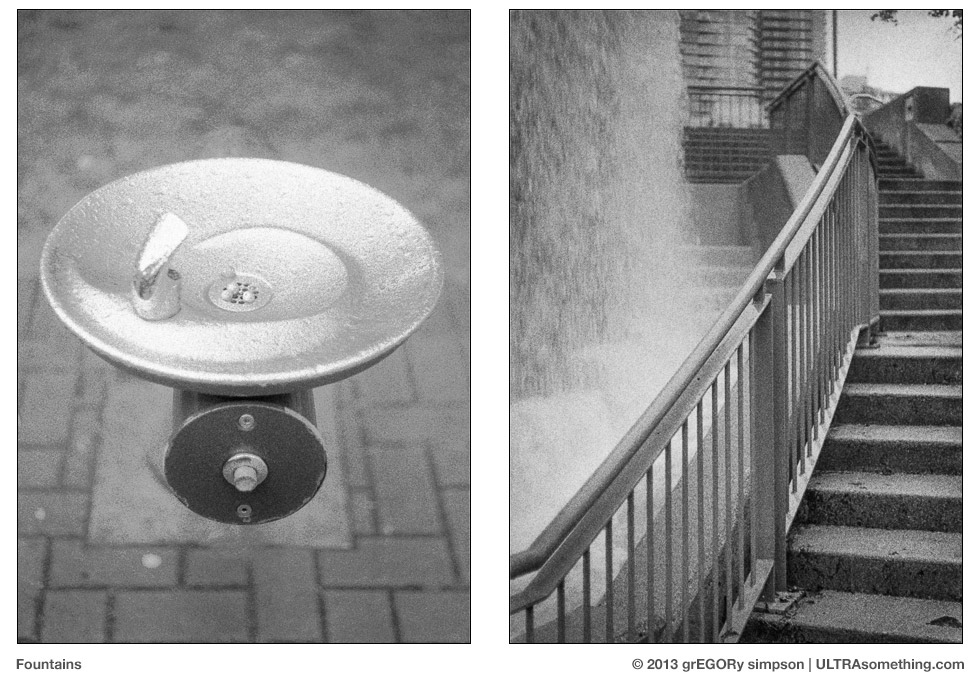

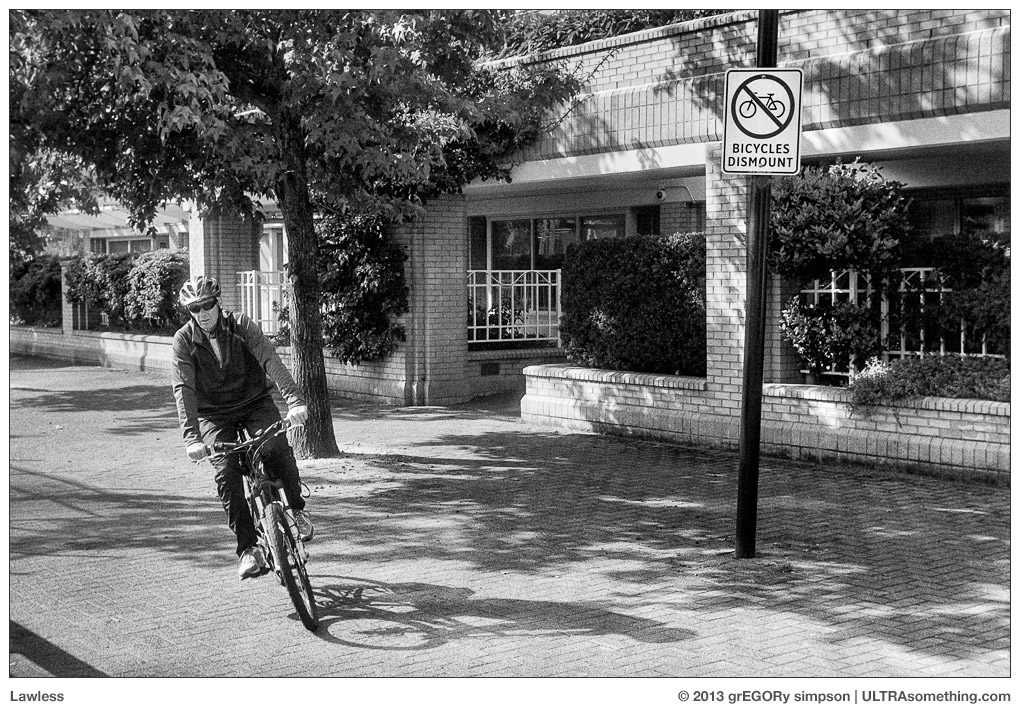

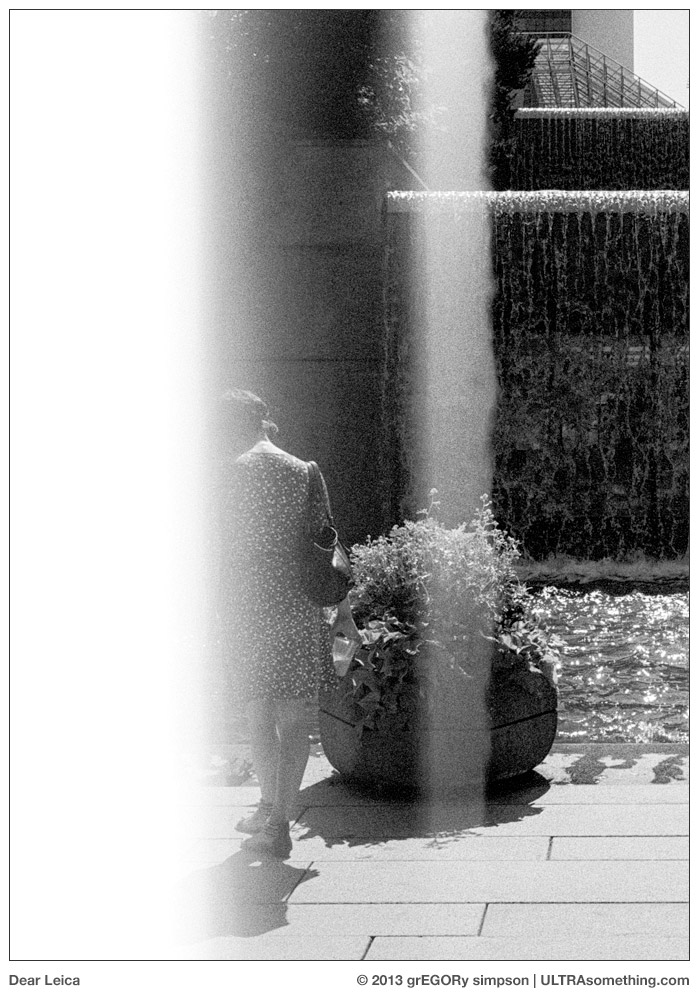

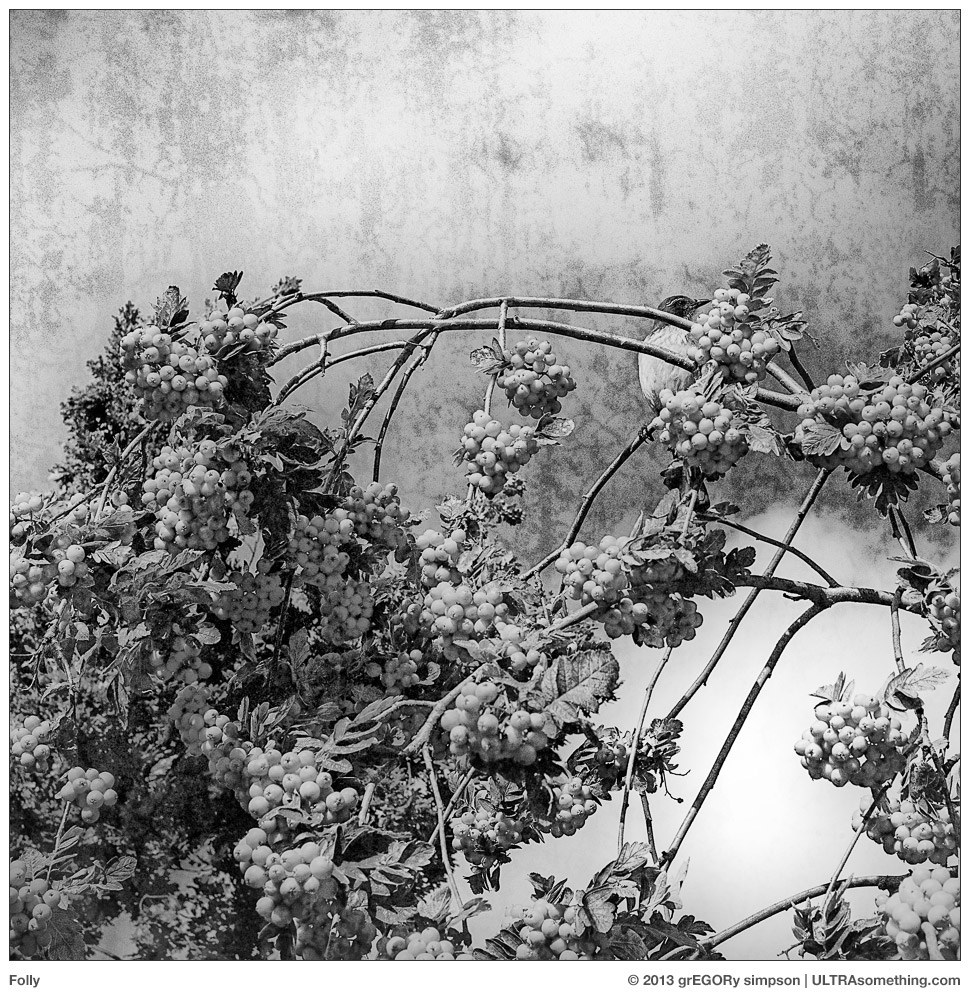

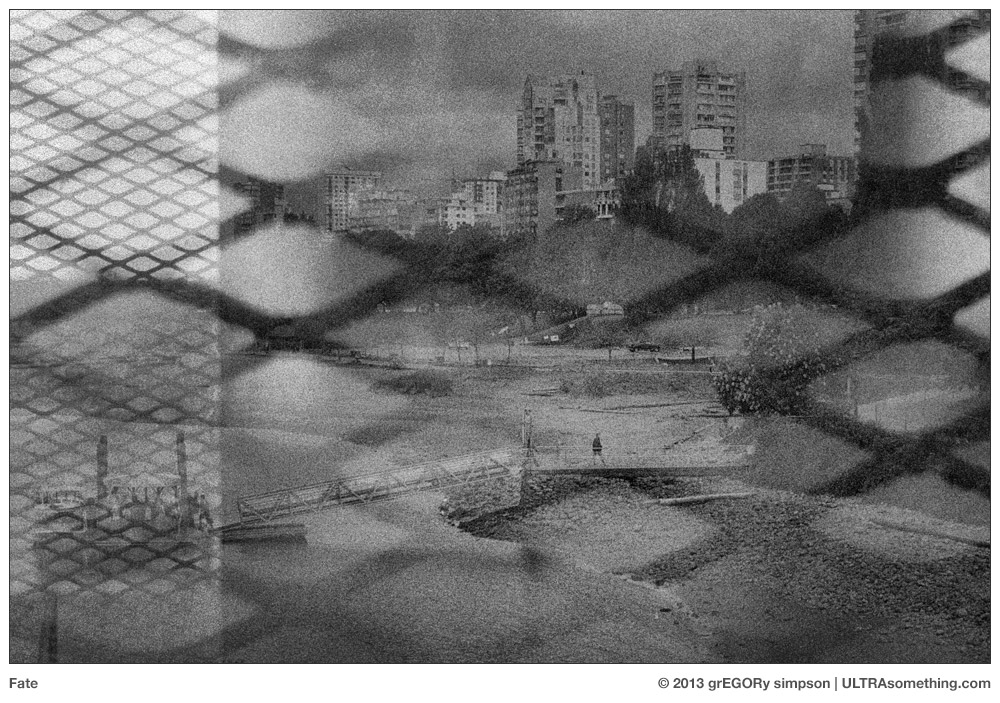

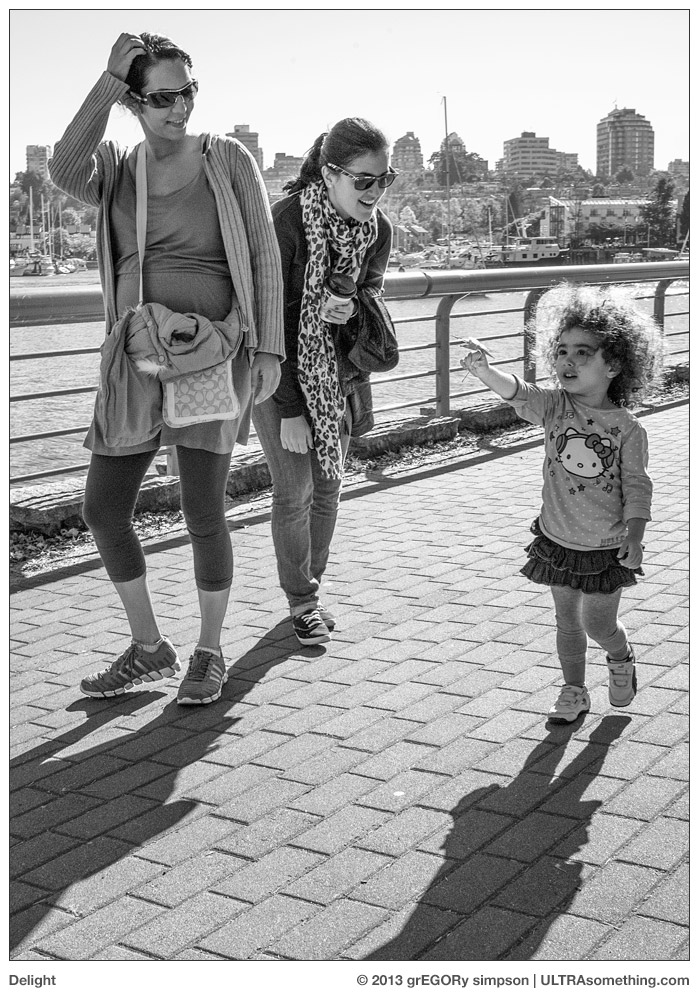

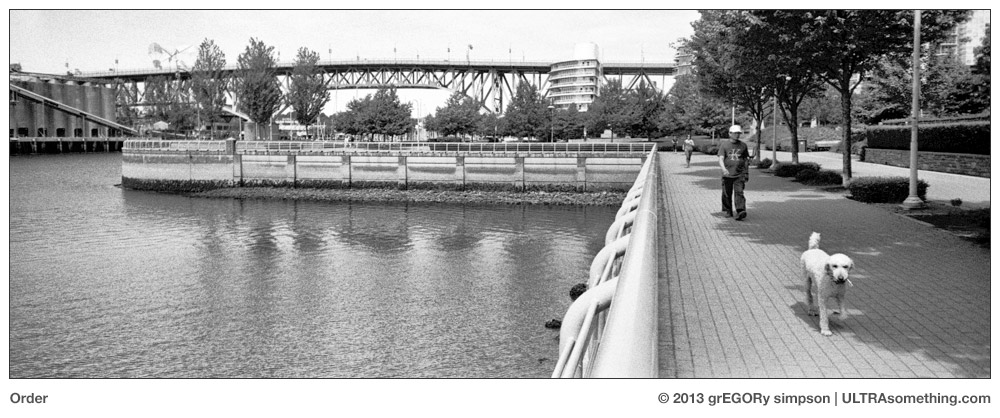

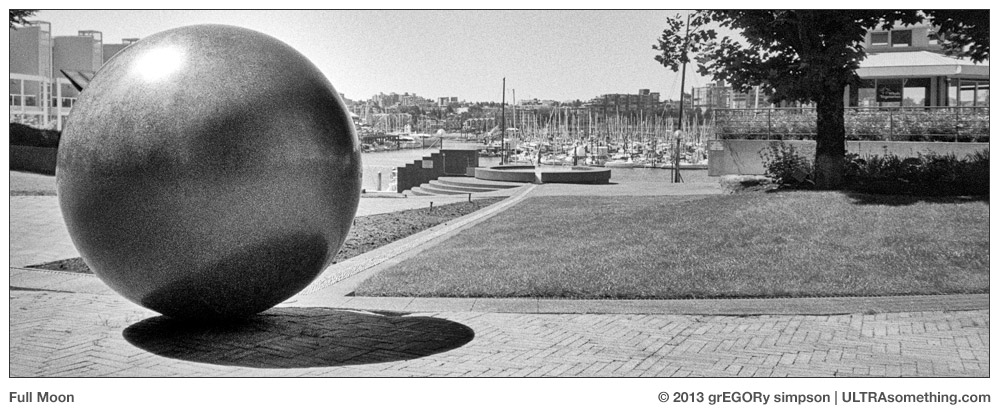

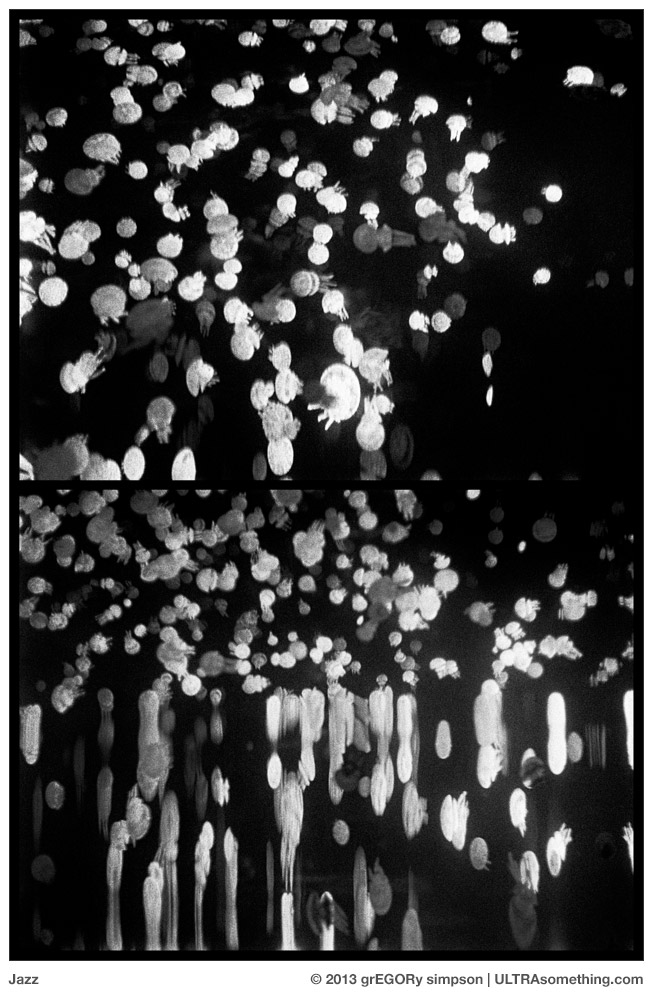

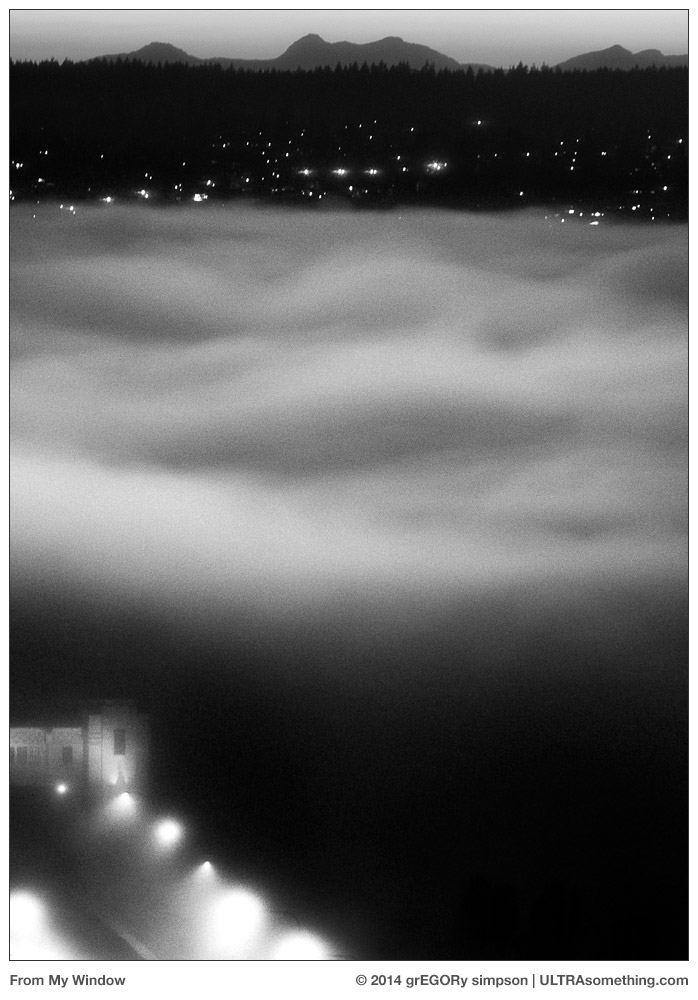

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “In Viscera” was shot with an Olympus OM-D EM-1 fronted with a Lumix/Leica DG Summilux 25mm f/1.4 lens. “From My Window” was shot with an Olympus OM-D EM-1, this time fronted with a 120mm f/2.8 SMC Pentax-M lens via a Voigtlander K Adapter. “False Creek, Vancouver” was also shot with an Olympus OM-D E-M1, now adorned with an Olympus M. Zuiko Digital ED 60mm f/2.8 optic. Everything else was shot with a Ricoh GR: “Pet Friendly” on the way to grab some carry out Indian food; “Branch Manager” on the way home from Costco; “Prelude to a Fracas” on a walk to retrieve my car after the dealer completed its oil change; “The Leaf Stalker” on my way to the grocery store for a jug of milk; “The New Hoodie?” on my way back from the drugstore (both shots in the diptych taken within 1 minute of each other); and “Innocents” on the walk home after dropping my car off for the previously mentioned oil change.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.