To my left there are photos to take. To my right, the same. Above me, below me and behind me are photo opportunities. But the opportunities are not always obvious. Often, they hide in plain sight — stacked, layered and entwined into a fortress of visual noise so dense we fail to perceive them as individual photo subjects. Instead, we observe only a single cohesive wall of babel.

Our eyes see so much, but we comprehend almost nothing.

Our cameras see almost nothing, but allow us to comprehend so much.

Cameras achieve this paradoxical advantage by removing the inimical distractions of visual clutter and continuous motion. With the resulting photograph, we are free to study the subject in isolation — to comprehend its rhythms and absorb its meanings.

I have learned to intuit my surroundings as I know the camera will see them. Each day the camera accompanies my every journey. Each day I record new images on film or on memory cards. Most I dismiss, but every week there are several images that capture and hold my attention for a period of time. Even though I find these photos emotionally or aesthetically rewarding, I rarely publish them. I feel responsible for each of my minuscule snippets of time and place, and believe that an image — rescued from the obscurity of so much transitory visual noise — deserves a certain amount of space in which to contemplate it. The fewer photos I choose to publish, the more space I give to those I do.

At least that’s been my theory — quality trumps quantity. It’s always better to have a few good things than a few hundred shoddy things. It’s why I don’t publish every photo I happen to like. It’s why I don’t shop at Walmart, or have drawers full of Pet Rocks, Chia Pets, Koosh Balls, Thigh Masters, Snuggies, ShamWows, or cameras with built-in smile detectors.

But there’s a trend amongst modern photographers to publish nearly every photo they take. Event photographers, for example, actually promise their clients a minimum number of photographs (usually in the thousands) for a particular event. I admit freely that I don’t understand this. The beauty of photography lies within the purity of the individual image — of a subject and a moment, freely observed without constraint. To bombard the viewer’s visual sense with an excess of images nullifies the seductive advantages of still photography. When photographers publish a thousand images from a single time and place, they have not allowed photography to fulfill its mission — they have merely replicated the visual noise.

Does the public really prefer to flip through a thousand insipid photographs, rather than contemplate one or two meaningful and iconic ones?

Apparently.

This became quite clear in a conversation I had recently with a successful businessman and venture capitalist. We were discussing the business aspects of photography and he told me, in essence, “If I had the choice of publishing one higher-quality professional photograph or publishing ten lesser-quality consumer photos, I would choose the ten photos every time. So would anyone else. The market has spoken.”

I’ve slowly come to realize the error in my ‘quality trumps quantity’ theory, and my belief that someone might actually spend 15 seconds absorbing one of my photos. A spokesman for the Louvre once stated that the average tourist spends 15 seconds looking at the Mona Lisa! If 15 seconds is all people spend looking at the Mona Freakin’ Lisa, how long can I realistically assume someone will look at one of my photos?

Perhaps we, as humans, actually want visual noise. It is, after all, what bombards us every second of every day. It’s what we’re accustom to and what we’re comfortable with. Photography is not the language of everyday life, but a language unto itself — more poetry than prose, and more figurative than literal. Photographs reveal that less is more. But for the average person, more is more.

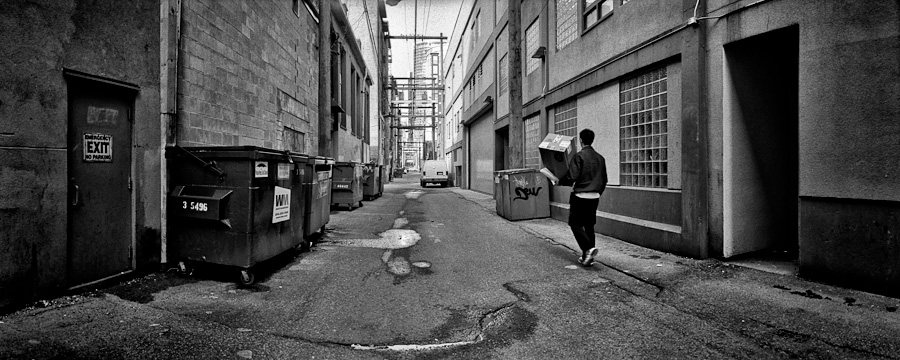

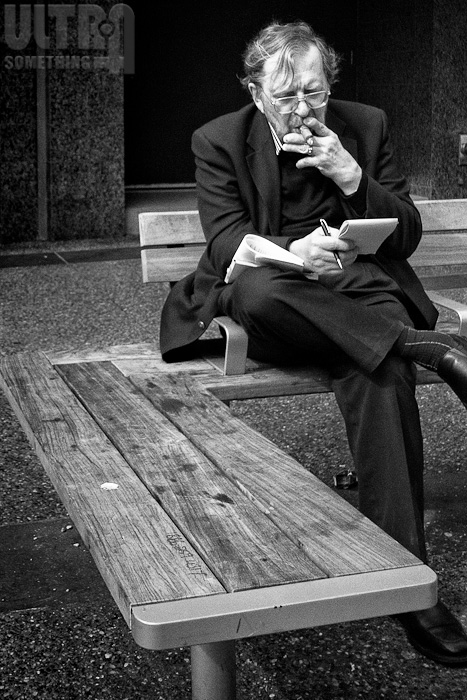

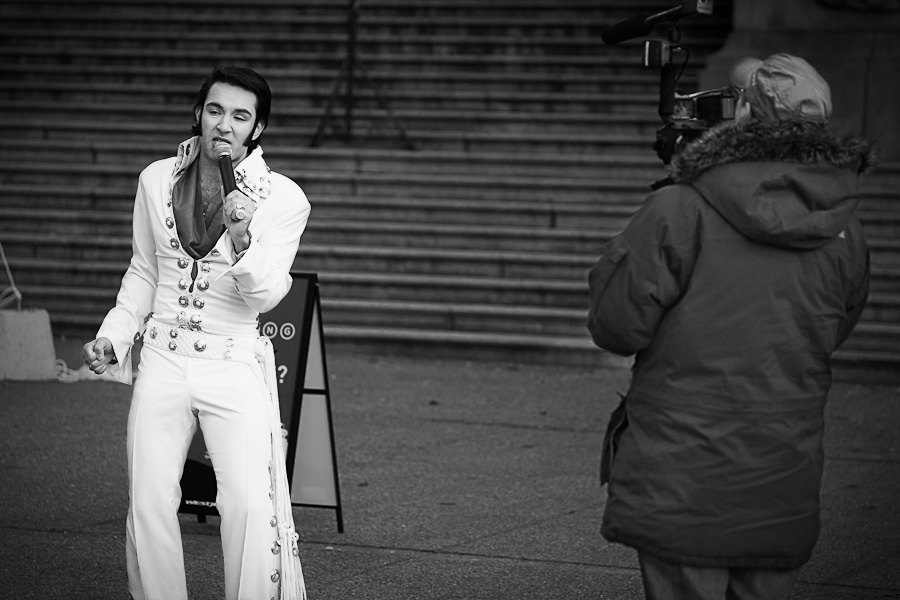

So I got to thinking (something frequent readers know is rarely a good thing for me to do), “Maybe the paucity of photos I publish does not guarantee that each image will ultimately be viewed for a longer period of time. Maybe people are preprogrammed to look at photos for only a fraction of a second, meaning the cumulative time spent absorbing my photos is significantly less than for the guy who posts thousands.” So against my nature, I decided to do something bold and sprinkle this article with photos I would never normally post. I chose them not for their poignancy, quality or insight, but simply because they were my favorite shots from the previous 48 hours or so.

So I got to thinking (something frequent readers know is rarely a good thing for me to do), “Maybe the paucity of photos I publish does not guarantee that each image will ultimately be viewed for a longer period of time. Maybe people are preprogrammed to look at photos for only a fraction of a second, meaning the cumulative time spent absorbing my photos is significantly less than for the guy who posts thousands.” So against my nature, I decided to do something bold and sprinkle this article with photos I would never normally post. I chose them not for their poignancy, quality or insight, but simply because they were my favorite shots from the previous 48 hours or so.

The problem is that I know I don’t take two or more worthwhile photos every day, so such haphazard publishing makes me feel as if I’m contributing to the noise, rather than clarifying it. Ansel Adams once said “twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.” I gotta go with Ansel on this one.

Mind you, quantity isn’t always bad — it depends on the context. Earlier this week, I ordered Bruce Davidson’s three volume photographic set, “Outside Inside,” which contains a whopping 834 photographs. I can hardly wait to get it. So why would I consider 1000 wedding photos to be “noise,” but not 834 Bruce Davidson photos? Because Bruce’s collection spans 55 years of his photographic career. That works out, on average, to about 15 photos a year — Ansel-like quantities. The book does not contain hundreds of images from a single time and place — it spans over half a century and traverses the world. Each image is carefully chosen and expertly crafted. I’ll likely spend the rest of my life looking at these photos, while finding something new with each subsequent viewing.

So what of this “market” that “spoke” and said our photos have no value? “The market” is not some autocratic God-like entity that dictates our beliefs. “The market” is merely a reflection of our own ideals and values. This market that assigns no value to our photos is the same market that allows movie theatres to sell popcorn at a 1,275% markup, or values Michael Jackson’s leather jacket at $1.8 million. The market may speak, but it only repeats what we tell it. If we as photographers devalue our own images by a failure to edit, then we only add to our own demise.

So the next time you find yourself uploading several hundred megabytes worth of photos from an afternoon visit to the local park, or 70 pictures you took of your cat poking its head into a paper bag, maybe you should ask yourself this: might a single photo not be better? Might one photo not speak for the rest? One or two of us aren’t going to change what “the market” says, but one or two million might. That reminds me — I really gotta increase ULTRAsomething’s subscription base…

©2011 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “Forced Deco” is something I stumbled across while taking a circuitous path to the store for milk. I’ve seen this piece of public art a thousand times, but this time I noticed that from a certain angle, with the sidewalk in the background and the sun just so, I could capture a sort of “art-deco” type image, even though there was nothing actually art-deco about the sculpture. It was shot with a Leica M9 and a v4 35mm Summicron lens. | “Discarded Beverage” was shot in a back alley while I was taking a shortcut to the drugstore. It is what it’s titled: a photo of a discarded beverage. Shot with a Leica M9 and a 21mm pre-ASPH Elmarit-M lens. | “Stonewalled” is a classic example of “personal” photography — the sort of shot I love because I think it drips with emotion and wonderment. Most people would counter that it drips with blurriness and pointlessness, which is why I rarely post such shots. Taken on my way home from the drugstore with a Leica M9 and a 21mm pre-ASPH Elmarit-M lens. | “Dental Ascent” is pretty much as described. I had a dental appointment, and was climbing these stairs to the dentist’s office. It was a hot day, and I felt a little spacey going up the stairs. The photo is an accurate reflection of my mood. It was shot with a Leica M9 and 21mm pre-ASPH Elmarit-M lens.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.

In 1952, pianist David Tudor stepped on stage to perform composer John Cage’s latest work, 4’33”. He sat at the piano, closed the lid over the keyboard and, for the next 4 minutes and 33 seconds, played absolutely nothing.

In 1952, pianist David Tudor stepped on stage to perform composer John Cage’s latest work, 4’33”. He sat at the piano, closed the lid over the keyboard and, for the next 4 minutes and 33 seconds, played absolutely nothing.