Short of taking photographs, few things excite a photographer more than planning their next major camera purchase. Conversely, short of a trip to the dentist, few things excite a photographer less than contemplating a backup camera strategy. After all, money spent on a backup camera is money you won’t have available for that next primary camera body; or that fast prime lens; or that slick new flash; or that dream photo excursion.

Surprisingly (or maybe not), I actually know several working photographers who do the unthinkable — they go on assignment without any backup camera. Their logic, such as it is, seems to be based on the legendary ostrich tactic — if they don’t think about the worst case scenario, then they won’t experience the worst case scenario. But all it takes is a single camera failure to nullify the years of hard work you spent building your reputation. Clients don’t want to hear “Sorry, my camera broke.” They’re not paying for excuses — they’re paying for images. And the day you fail to deliver those images is the day you’ll say “I wish I had thought about a backup strategy.”

But here’s the thing — backup cameras don’t have to be boring. In fact, choosing the right backup camera may actually unlock a world of previously untapped photographic possibilities, while simultaneously helping you avoid the potential pitfalls of the single camera gamble.

So how can you put the “up” into your backup camera? What are some of the possible backup strategies, and what are the pros and cons of each? So glad you asked…

Strategy 1: The Clone

The most literal backup solution is also the most obvious — a second, identical model of your primary camera.

UPSIDE: Simplicity factors heavily into the clone strategy. Owning two identical bodies means you’ll cope with only one learning curve; it means you don’t have to rethink your techniques when switching to the backup camera; and it means any photographs shot with the backup will be indistinguishable from those shot with the primary camera. Identical bodies share accessories, so you don’t have to carry a different type of battery, a different type of quick release bracket, additional lenses, or an additional pocket manual. It also helps the photographer transition easily into a “two body shooter.” If you’re a zoom user, a 24-70mm on body #1 and a 70-200mm on body #2 will pretty much insure you get any shot you need. And, should one body go down, you can keep shooting without missing a beat.

DOWNSIDE: Many working pros choose a camera with a full-frame 35mm sensor as their primary body. Adding a second Nikon D3x, Canon 1Ds, or Leica M9 can be quite cost prohibitive. And if you’re shooting digital medium format, you’re probably still paying off a camera loan. So, chances are, you’re not overly receptive to the idea of going still further into debt. Even if you’re fortunate enough that cost isn’t an issue, there’s still another downside to the clone strategy — flexibility. No one camera system is perfect, no matter how expensive it is. You may have spent a fortune on a Phase One, but adding a second isn’t going to make you any more capable of shooting in low light. Your second D3x isn’t going to be any more “stealthy” than your first, and that second Leica M9 still won’t double as a wildlife camera.

Strategy 2: The Crop-a-Doodle-Do

The second backup strategy is to purchase a smaller “prosumer” version of your primary camera. For example, a full-frame Canon user might choose a cropped sensor Rebel or xxD model to serve as backup. A full-frame Leica M9 shooter might consider an old M8 or Epson R-D1 as a cropped sensor backup.

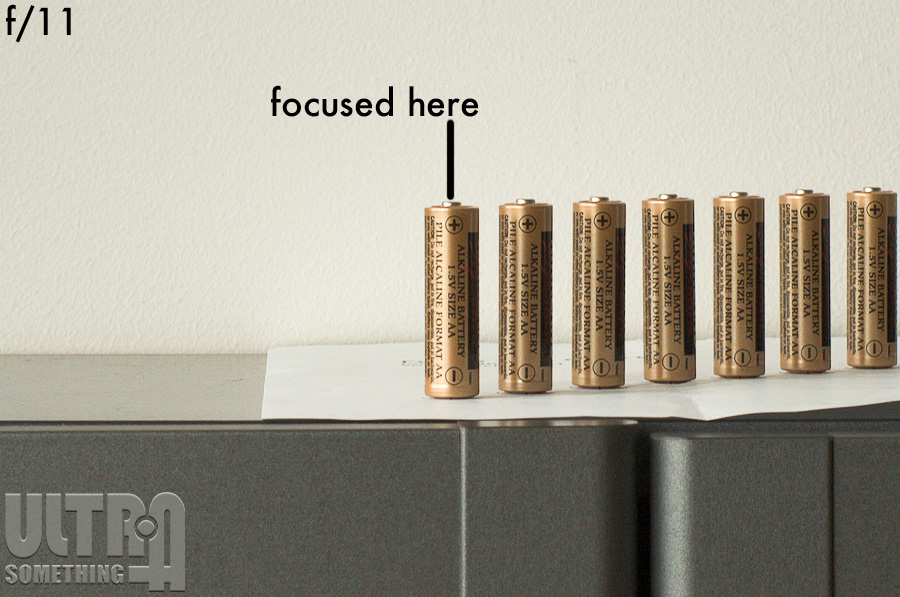

UPSIDE: As with the cloning strategy, the “crop sensor” solution helps to limit the amount of additional backup gear you need to carry. Since you’ve chosen a cropped version of your primary camera, it will (in most instances) mount all the same lenses as your primary camera. If the backup camera is made by the same manufacturer as your primary camera, there is probably enough similarity between operating systems that you can move from primary to backup without too much discombobulation. In almost every instance, choosing a prosumer camera to backup your pro model will greatly diminish the cost of owning a backup, which means you’re more likely to actually do it. And there’s another advantage over the clone strategy — flexibility. Although a cropped sensor body will take the same lenses as your full-frame primary camera, those lenses will behave “differently” on the backup body. Specifically, the crop body will act as both a free tele-converter and depth-of-field extender for each lens. This gives you options should you wish to employ both bodies on assignment. In some instances, it may even allow you to carry fewer lenses. For example, if you’re a full-frame Canon shooter and you add an old 50D as a backup body, the 50D’s 1.6x crop factor will change the field of view of any lens you mount on it. A 35mm mildly wide lens on your 5DmkII becomes a 56mm mildly telephoto lens on a 50D. Similarly, an 85mm lens on your 5DmkII becomes a 136mm lens on your crop camera. So, with only two lenses in your bag, you have access to four different focal lengths: 35, 50, 85, and 135. In addition, that crop camera will have extended depth-of-field, which allows you to pick-and-choose the camera body based on the shooting scenario.

DOWNSIDE: Obviously, a different body may require different accessories, such as quick release brackets and batteries. So you need to factor in the additional cost (and weight) associated with having duplicate sets of batteries, chargers, and the like. You also need to consider that, should your primary camera die, your widest lens might not be wide enough on a crop body. This may necessitate that you carry an additional extra-wide lens to cover any worst-case scenario.

This is exactly the strategy I employed when I worked as a photographer for BC Parks. I would often drive a couple of hours to a particular location, then spend another couple hours hiking up some mountain. The last thing I wanted was for my camera to fail once I reached my final destination. So I carried a 40D as backup to my 5D — using it as both “backup” and “teleconverter” (to reduce the number of lenses I needed to lug around in my backpack).

Strategy 3: The Pocket Porty

If Vogue, National Geographic, or even the bride’s CEO daddy aren’t footing the photography bill, it may be difficult to justify the added expense of a second system body — regardless of whether it’s a clone or a crop of your primary camera. But a small photography budget does not excuse you from your responsibilities. You still have a client that expects his money’s worth, and you still have a professional reputation to uphold.

One of the most popular solutions to this dilemma is the humble “enthusiast” camera. In general, these enthusiast cameras have built-in, non-interchangeable zoom lenses, and are similar to their pocket-friendly consumer-oriented camera cousins. But, unlike their cousins, the enthusiast models include additional features required by working photographers — features such as manual exposure, a hotshoe (which can be used to trigger external flash), and RAW file support. Canon’s G-series (currently up to the G12) and Panasonic’s LX series (now at LX5) are both very popular and capable examples of enthusiast cameras.

UPSIDE: The Pocket Porty is likely to be both your least expensive backup option and your most portable (though it will necessitate carrying an extra type of battery and charger). Its diminutive dimensions might just entice you to slip it into a pocket and, once there, you’ll probably discover all sorts of scenarios (like candids) that benefit from its non-threatening appearance. Because it uses its own built-in lens, rather than your system lenses, you’re not tied into one particular brand or form factor — it can back up any primary camera you currently own.

DOWNSIDE: Image quality, ergonomics, and responsiveness are the biggest prices you’ll pay for all that portability and frugality. Images from a small sensor simply won’t hold up to those taken with a full-frame or APS-C sized sensor. If your client’s demands don’t extend beyond web publishing, that’s probably OK. But if your images are destined for print, neither you nor your client may be satisfied with the results. Similarly, the hostile combination of tiny buttons and labyrinthian menus make these cameras much harder to control than a larger system camera. And their contrast detect focusing and general lack of a quality viewfinder make it difficult to both frame your shots and time them decisively. Then there’s the matter of your own image — should your system camera fail and your enthusiast compact be forced into action, the client may wonder why he’s paying pro rates for “point and shoot” photography.

Recently, photographers have started to see a new breed of enthusiast cameras that feature larger, APS-C size sensors. These cameras directly address one of the two major complaints about the previous decade’s enthusiast cameras — image quality. Cameras like the Sigma DP series, the Leica X1, and the upcoming Fuji FinePix X100 all use larger sensors, while retaining the “pocketability” requirement of their smaller sensor siblings. All three of these cameras stick to the concept of non-interchangeable lenses but, curiously, dispense with the zoom lenses employed by their forefathers. Instead, each sports a high-quality prime lens — generally in the 35-40mm range. While I’m exactly the sort of photographer who will always choose a prime lens over a zoom, this limitation may ultimately make these large-sensor compacts less appealing for “backup” duty. After all, the idea behind the backup camera is that, in a pinch, it can substitute for your big system camera and bag full of lenses. But without a zoom, your backup becomes limited to photos of a single focal length. What if that 35mm focal length isn’t the length your client needs? While this new breed of enthusiast camera is, indeed, a more exciting photographic tool than the G12/LX5 ilk, the jury (me) is still out on whether it’ll make a suitable backup camera.

Strategy 4: The Geezer

Throughout the entirety of the 20th century, talented photographers created beautiful images on film — photographs with the power to inspire us, touch us, teach us, or delight us. The advent of digital technology does not suddenly negate a photographer’s ability to create beautiful photographs on film. Yet many modern photographers seem to think that film is somehow beneath their talent and vision — as if shooting film will somehow make their photographs less valuable. Hogwash. Many of today’s top digital camera systems have their origins in the days of film — Yesterday’s Mamiya, Pentax, Canon, Hasselblad, Nikon, and Leica lenses will still perform on today’s digital bodies and, conversely, today’s lenses will often still perform on older film-based bodies. Why not back up that expensive full-frame digital body with a top-of-the-line film-based equivalent?

UPSIDE: Although your backup camera is film, it’s still from the same system as your primary digital camera — meaning it shares many of the same lenses and peripheral items. Although modern “wisdom” says “digital is better than film,” it’s really all about how you define “better.” Camera manufactures have spent a decade hammering home the idea that “better” means “sharper images and more resolution” — two characteristics that, not coincidentally, are indicative of what digital does best. But what if “better” means “greater dynamic range, a more natural and pleasing response to both shadow and highlight regions, and better tonality?” These are the merits of film — attributes that have been downplayed by camera marketing departments in the rush to digital. The fact is, neither film nor digital is better — they’re just different. And, as such, having the ability to shoot both can be a real boon to your photography. Here in rainy Vancouver, I’ve found another upside to shooting film — my mechanical film bodies have no electrical components, making them much more conducive to shooting in inclement weather. Another upside to film is that, thanks to the successful marketing campaigns of camera manufacturers, you can purchase some wonderful professional bodies for less than you’d pay for that Pocket Porty enthusiast camera — and with increased handling ability, flexibility in lens choice, greater durability, and drastically improved image quality.

DOWNSIDE: Film has a recurring cost that digital “lacks.” In reality, professional digital cameras are rendered ‘obsolete’ every couple of years, while professional grade film cameras can last decades. So the ongoing cost of film and processing is really more about perception than reality. But the fact is, should your primary camera break and your film camera be forced into action, you will incur additional film/processing costs for the photos you take. Also, a film-based workflow is slower — after 36 photos you need to stop, rewind, and reload. Similarly, film lacks digital’s ‘instant gratification’ factor since it needs to be developed, dried, and scanned before the client can see it. And film also lacks digital’s convenient ability to change ISO at any time — once you load a roll of film, you’re stuck with that ISO for the next 36 shots. Finally, some misguided clients — driven to delusion by years of successful digital camera marketing efforts — now demand that photographers deliver files that exceed a certain number of megapixels. This number often exceeds the file size delivered by all but the most expensive drum scanners, making post-processing even more tedious and expensive.

The choice of whether or not to use film as a backup to digital rests more on the expectations of your client than on any other factor. Today, many commercial clients expect to sit beside the photographer and instantly review each photo, as it’s taken, on a tethered computer monitor. News organizations expect photographers, while still in the field, to wirelessly upload images to a central server for immediate publication. But if a photographer is blessed with less-controlling clients, he (and the client) might both just discover that film’s upsides may actually negate its perceived downsides. In the past year, I have rethought my own backup strategy, and am no longer backing up my Leica M9 with a cropped-sensor M8. Instead, I’ve opted for two backup solutions: film is one (compliments of an M6 TTL and an M2). The other is discussed next…

Strategy 5: The Transformer

These cameras, like their toy- and movie-industry namesake, allow a photographer to transform his entire photography system from one type into another. The current spate of so-called “mirrorless” cameras are a classic example of how you can achieve this magical transformation. Many mirrorless system cameras, like Micro Four Thirds or Sony NEX, are capable of mounting lenses from other camera systems via an adapter and, as such, can function as backup cameras.

UPSIDE: With the right adapter, these cameras can mount all sorts of different lenses from all sorts of different camera systems. This means, in a pinch, that they can be coerced into “backup” camera duty. Their real beauty, however, lies in their transformative properties. Look, for example, at the case of my Panasonic DMC-GH2, which sometimes serves as backup and “second shooter” to my Leica M9. With a Novoflex adapter, my GH2 can mount all my Leica M lenses. The GH2 has a 2x crop factor, meaning a 21mm lens becomes a 42mm lens, a 50 becomes a 100, and so on. Since the M9 is not well-suited for telephoto use, the GH2 opens a world of new possibilities — converting that bag full of M-mount lenses into useful telephotos. In addition, one focuses the GH2 by looking THROUGH the lens (like an SLR), rather than looking through a separate viewfinder (like the M9). This also increases the capability of the M-mount system, since the GH2 transforms the M-system rangefinder lenses into an SLR-type system. With the addition of a GH2 body, those M-mount lenses become video lenses. Live view becomes a reality. The articulating LCD lets you put the camera in all kinds of odd locations, and depth-of-field can be previewed right on the screen.

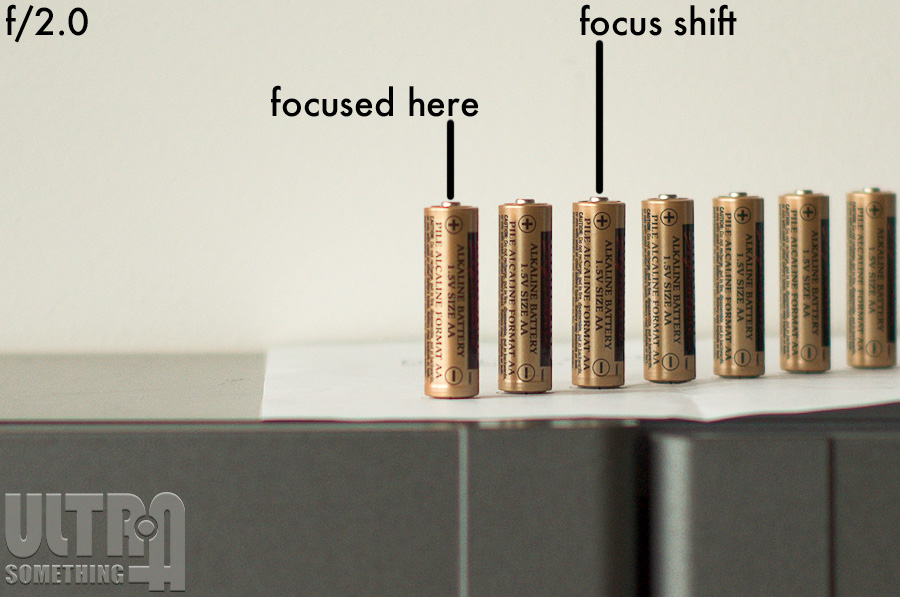

DOWNSIDE: That same tele-converter function, which makes the GH2 so useful as a “second shooter,” can be somewhat detrimental should my M9 actually fail. While I can carry on shooting with the GH2, I would lose the ability to shoot wide angle. For this reason, carrying the GH2 as “backup” necessitates that I carry an extra lens or two — perhaps something like a Voigtlander 15mm, or one of the wider Micro Four Thirds system lenses. This, of course, adds a bit of weight to the travel kit. Also adding weight to the kit is the additional batteries and charger required by the GH2. Image quality will also suffer should your GH2 be forced into “backup” duty. Its smaller sensor simply can’t deliver the same dynamic range, resolution, or noise characteristics as a full-frame camera. And, since the sensors contained within these cameras have not been optimized for M-mount lenses, images shot with adapted Leica lenses tend to get a bit soft in the corners. Ultimately, the image quality tradeoffs are something you’ll need to weigh against your client’s needs and your own aesthetics.

Conclusion

Many pros consider backup cameras to be a necessary evil but, in reality, they’re a necessary “good.” When you stop thinking of your backup as “only” a backup, and start thinking of it as your “second shooter,” you bring a host of additional possibilities and options to your photography. As I wrote earlier, no single camera is “perfect.” Adding a backup camera can negate many of your primary camera’s imperfections, while doubling as a career-saving insurance policy. Just because your camera hasn’t yet failed doesn’t mean it won’t. Don’t let complacency be your downfall. Don’t feed the ostrich.

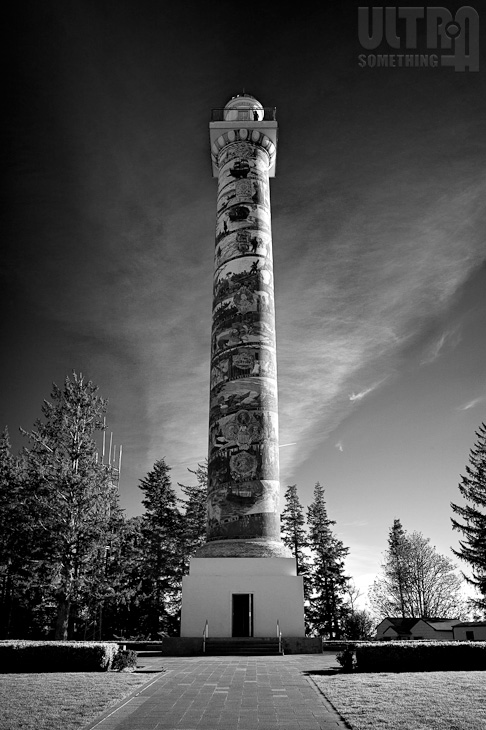

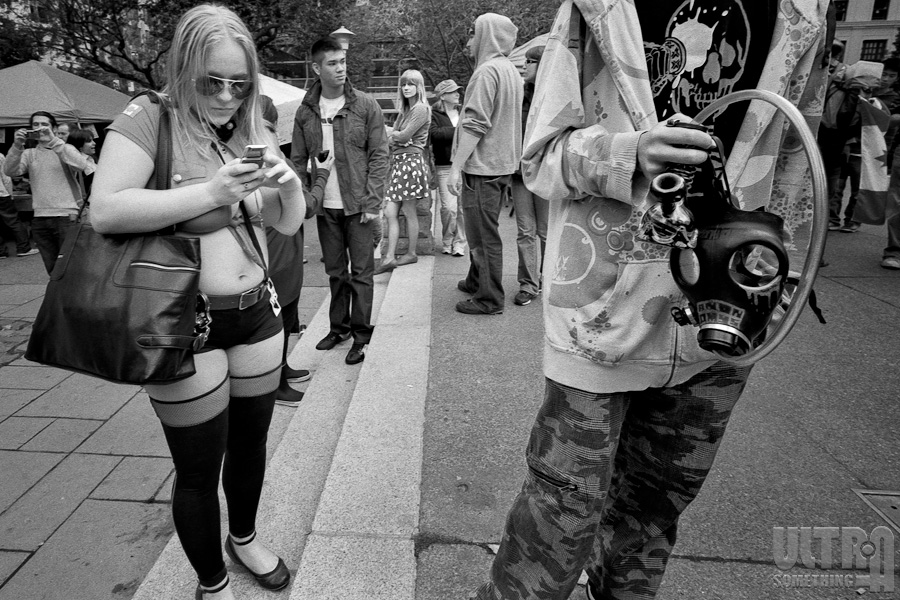

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “A Curious Pigeon” and “Ménage à Pod” were both shot using a Leica M2 with a Leica 28mm f/2 Summicron lens and Tri-X 400 developed in Ilfotec DD-X. “Alone, Under a Tree” was shot with a Leica M2, 21mm f/2.8 Elmarit pre-ASPH lens, and Tri-X 400 developed in Ilfotec DD-X. “Generation Skip” was shot using a Panasonic DMC-GH2 with a Leica 90mm f/2.8 Elmarit-M lens.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.