(Continued from Part 1)

In the mid-1990’s, I was an impetuous young(ish) photographer who couldn’t wait until the day I would boot my last film camera out the front door. In my career as a music products designer, I helped hasten the era of digital recording and software-based recording studios, and I was anxious for the same fate to befall the photography industry. But fifteen years later, with all my dreams and visions come true, a curious phenomenon emerged — I had developed a burning desire to supplement my digital shots with film.

I decided to purchase a mechanical Leica M film body, since it could share lenses with my digital M while doubling as its backup. Film cameras aren’t exactly in high demand — quite the opposite, really — so I knew I could take my time and choose wisely. Almost immediately, a Leica M4-P appeared for a ridiculously low price. I knew enough to know it was a good deal, and the M4-P was one of the models I desired. But, suddenly, I started to vacillate — questioning my motives, my reasons, my desires. By the time I picked up the phone to get the camera, it had sold. “No problem,” I thought, “there’ll be plenty of other bargains to capitalize on.”

So I waited… and waited… for nearly 6 months. Until finally, last fall, I found a beautiful M6 TTL for a rather respectable price. I touched it, fondled it, and listened to its silky, quiet shutter. And then I vacillated — wildly. The next day, when I returned to the shop to get the camera, it had sold.

I realized I needed to find a way to circumvent my trepidation. In other words, I needed to test the film waters using the cheapest possible approach. So, last December, I purchased a Yashica Mat TLR. I figured it would be a fun way to experiment with the process and decide, once and for all, if I was experiencing premature senility or if there was merit to my film desire. As it turned out, I love the Yashica Mat and the photos I took (and continue to take) with it. There are, however, a few things I don’t love about it — the bulkiness, the 12-picture limit (per roll) and, most importantly, the fact I can’t carry it for two blocks without being stopped by a dozen people. Everyone wants to ask me about that camera. It draws so much attention on the streets that I rarely get the chance to actually take photos. Come to think of it, maybe the 12-shot limitation isn’t a limitation after all.

In any event, the Yashica Mat experiment paid off, and it helped confirm the validity of my original plan: to get a mechanical Leica M film body to back up my digital Leica M.

Which Leica?

With renewed conviction, I went back to work — researching and fine-tuning my purchase options until I narrowed my “active” search list to four possible bodies:

With renewed conviction, I went back to work — researching and fine-tuning my purchase options until I narrowed my “active” search list to four possible bodies:

MP: The most desirable, the most expensive, and therefore the least likely of my four options. If I shot film primarily, then an MP body would make more sense. But I knew this camera’s purpose was to provide an alternate look to my digital M, while serving double duty as its backup. Still, it wouldn’t hurt to keep my eyes open; just in case some doofus unwittingly dumped one on the market at a ridiculously low price — so it made my search list.

M2: I was instinctually drawn to this model, its build quality, and something magical about the way it fit my hand. I wasn’t overly concerned that it possessed framelines for only 35, 50, and 90mm lenses — though I do make frequent use of a 28. I was a little more concerned that the majority of M2’s are chrome, which I thought might be a bit too “flashy” on the streets. Black paint models are available, but they’re collectors items and, as such, command collector prices. I had another concern about the M2’s seemingly hostile film loading. Again, this wasn’t an insurmountable problem, though it did mean I might have to grow a third hand. I knew that a “rapid load” model appeared late in the M2 life cycle but, again, their rarity makes them collector’s items. Still, if I happened to find a good price on a tattered, bog standard M2, I planned to jump on it.

M4-P: This model, from the early 1980’s, sported the addition of 28mm framelines, plus a much friendlier film loading system than the M2. It fixed most of the problems inherent in the previous model M4-2, came in basic black, and was a staple of rangefinder-toting photojournalists (who, in the early 1980’s, were already anachronisms). Like the M2, it had no meter — but I rarely use one anymore.

M6 TTL: This model introduced a “wrong way” shutter speed dial that turns the opposite direction from every other film Leica (except the subsequent M7). But it does turn the same direction as the digital Leicas. Call me crazy, but not having to remember which way each camera’s shutter speed dial rotates is a big plus for me. Effectively, save for the addition of a very rudimentary light meter, there is little difference between any of the M6 bodies and the M4-P. At 15 years newer than the similarly built M4-P, and 40 years newer than the impeccably built M2, a well-used and budget-priced M6 TTL would be an ideal find.

Of course there are many other models of old Leica M bodies, and given the right set of circumstances (price), I would consider any of them. Every Leica comes complete with both baggage and bonuses. But, based on a diverse and personal set of criteria, these were the four primary models I sought… and sought… and sought. Finally, after another 6 month period, a handsome and nicely priced M6 TTL appeared from out of the blue. After twice missing excellent sales opportunities the year before, I acted swiftly and decisively. The M6 TTL was mine.

That Old Black Magic

Before I ever purchased this camera, I had decided — 18 years after giving it up — that I would make my triumphant return to shooting and self-processing black & white film. It was a decision I didn’t arrive at lightly. It was predicated partly upon my recent positive experience with re-scanning my old black and white negatives. It was also based on the “less is more” approach I opted to take with this particular camera. And, finally, it sprang from a fundamental observation that I have recently made: that of the hundreds of photographs I most admire, 95% of them were shot on black and white film.

That last reason’s worth exploring a bit more: It’s not that old cameras are inherently better than new cameras. It’s not that black & white film is better than color film, and it’s certainly not that film is better than digital. Frankly, I believe it’s this: because cameras were manual mechanical devices — void of metering or any other exposure aids —photographers were simply better back then. This is likely to be a point of contention but, hey, it’s my blog. Analog photography, unlike digital, required actual work. Hard work. If you didn’t have the talent, you didn’t stick with it. Photographers developed their own unique styles in an effort to distinguish themselves from their peers, and this resulted in some truly extraordinary photos. Today, it’s the opposite — everyone copies everyone else’s style and a certain photographic homogeneity has become the norm. For me, the limitations of black and white film force me to more carefully conceive, compose, and craft my photographs — much the same as it did for my old photographic heroes.

That last reason’s worth exploring a bit more: It’s not that old cameras are inherently better than new cameras. It’s not that black & white film is better than color film, and it’s certainly not that film is better than digital. Frankly, I believe it’s this: because cameras were manual mechanical devices — void of metering or any other exposure aids —photographers were simply better back then. This is likely to be a point of contention but, hey, it’s my blog. Analog photography, unlike digital, required actual work. Hard work. If you didn’t have the talent, you didn’t stick with it. Photographers developed their own unique styles in an effort to distinguish themselves from their peers, and this resulted in some truly extraordinary photos. Today, it’s the opposite — everyone copies everyone else’s style and a certain photographic homogeneity has become the norm. For me, the limitations of black and white film force me to more carefully conceive, compose, and craft my photographs — much the same as it did for my old photographic heroes.

So, with an M6 TTL in my hand, a brick of Tri-X in the fridge, and a half-dozen jugs of fresh chemical compounds under the bathroom sink, one journey had finally come to the end — and another was about to begin.

mmm-mmM6

If some of you think it’s odd that I’m reviewing a 12 year old camera, you obviously missed my review of the 52 year old Yashica Mat. But there’s a very valid reason for reviewing old film cameras — they still work. And they still pump out images every bit as good as they did when they rolled out of the factory. As I discussed in Part 1, film cameras are still relevant and will remain so for the foreseeable future. What isn’t relevant are the old, original reviews that accompanied these camera releases. We’re now living in a digital world, and any film camera review needs to address the camera’s use and features within the context of that digital world. That’s why so much of this review has focused on the tradeoffs between film and digital. There is, after all, an entire generation of photographers who have never shot a film camera, and who know nothing of film’s benefits, limitations, or workflow.

So, speaking of benefits and limitations, let’s dive into the ups, downs, and curiosities of the Leica M6 TTL, beginning with the positives:

An impeccable build quality insures this is a camera that will last a lifetime. This is, perhaps, a silly thing to mention in this review. It’s a little like reviewing a waterproof jacket and praising it for its ability to keep you dry. Quality is the very essence of the Leica M-series and, as such, you expect a build quality that exceeds all other 35mm cameras. This is a camera I am not afraid to use anywhere, any time, and in any environment — and its likelihood of survival will far exceed mine in particularly extreme conditions.

Maximum minimalism makes this camera your partner, not your master. Leica does not coddle their customers. They do not make cameras designed to hold their hand, or prevent the photographer from choosing settings that fly in the face of conventional photographic wisdom. After you select your film and load it into the camera, there are only three things a photographer ever need control: shutter speed, aperture opening, and focus. Every photo ever taken has been exposed using nothing more than these three parameters. And these are, indeed, the only parameters Leica presents to the photographer. There are no silly scene modes, no crazy auto-focus modes, and no annoying modes that prevent your shutter from releasing when you want it to. All the artificial intelligence that other camera manufacturers build into their modern cameras have a single goal: to set the camera’s shutter speed, aperture and focus so that you, the photographer, don’t have to. Personally, I want to be in control of the camera, not a computer program. Leica understands this, and the M6 adheres to the belief that the photographer knows what he or she is doing.

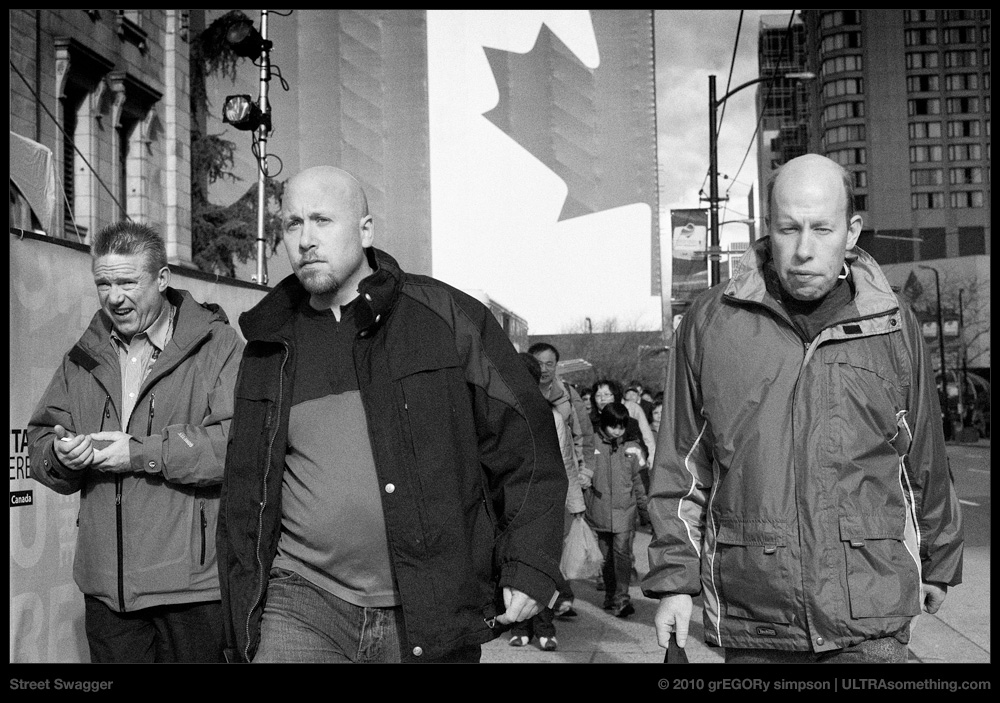

A magically soft shutter sound that doesn’t draw attention to the camera. You could argue that the totally silent electronic shutters populating modern point-and-shoot cameras make them even more ideal for surreptitious shooting than the Leica, but you’d be wrong. If we ignore all the zillion other reasons why point-and-shoots fail as effective street cameras, and concentrate solely on the shutter, we quickly see that point-and-shoot electronic shutters have a significant lag between the time you press the shutter, and the time it actually takes the photo. The M6 triggers the instant you ask it to — insuring that you don’t miss the desired moment. The whispered little “snick” sound passes unnoticed in all but the most quiet of environments.

Silky smooth film advance. Back in the film days, cameras featured all sorts of ways for the user to cock the shutter, and advance the film to the next frame: cranks, dials and, in the later days, noisy electric motors. With every film camera I’ve owned, I always had a sort of mild trepidation each time I advanced the film. Sometimes the film would jam. Sometimes it would slip the sprocket and fail to advance. Inevitably, in the heat of a frenzied moment of action, lesser cameras would lock up in the flurry of vigorous frame advances. Even my “new” Yashica Mat locks up occasionally, and I treat it as gently as a newborn bunny. The Leica M6? Effortless. Dependable. Confident. Assured. No matter how vigorously I thumb its frame advance lever, it’s never locked up nor complained. Again, the impeccable build quality permeates every corner of this camera.

Silky smooth film advance. Back in the film days, cameras featured all sorts of ways for the user to cock the shutter, and advance the film to the next frame: cranks, dials and, in the later days, noisy electric motors. With every film camera I’ve owned, I always had a sort of mild trepidation each time I advanced the film. Sometimes the film would jam. Sometimes it would slip the sprocket and fail to advance. Inevitably, in the heat of a frenzied moment of action, lesser cameras would lock up in the flurry of vigorous frame advances. Even my “new” Yashica Mat locks up occasionally, and I treat it as gently as a newborn bunny. The Leica M6? Effortless. Dependable. Confident. Assured. No matter how vigorously I thumb its frame advance lever, it’s never locked up nor complained. Again, the impeccable build quality permeates every corner of this camera.

Fast and easy film loading. Unlike some of the earlier M-series cameras (the M3 and the M2 come immediately to mind), the M6 loads effortlessly and dependably. Leica has always been known for the quirky way it loads film through the camera’s bottom, rather than by opening a door on the camera’s back. Leica claims this method results in a more rigid camera and, thus, a flatter film plane. Obviously, the flatter and more precise the film plane, the better the image quality. It’s true that I’m getting stellar images from this camera, but I have no idea how much the film loading method contributes to this quality. In any event, whether Leica’s claims are fact or fiction, there’s no denying that this is one solid camera that takes impeccable images, yet manages to load effortlessly. I don’t argue with success.

The built-in meter is pure bonus. Although I didn’t require that my M-model Leica have a built-in meter, its presence provides a definite benefit — particularly indoors, where my ability to judge light conditions is not as well honed as it is outside. Those who rely on modern matrix metering will likely think the M6 TTL’s rudimentary center-weighted meter is positively arcane. But, just like I prefer a camera that offers only shutter speed and aperture settings, I believe the simpler the meter the better. Unlike a matrix metering system, where I never know exactly what the meter’s actually metering, I know precisely what my M6 meter is telling me — the amount of light required to expose the middle 13% of the image to a Zone V average. I can then interpret those readings and mentally compensate for variations in the scene, then set my shutter speed and aperture accordingly. In other words, just like everything else on the M6 TTL, the meter doesn’t try to second guess the photographer. It doesn’t hold his hand or feign intelligence. Rather, it assumes the photographer is possessed with enough intelligence to correctly apply the information it provides. I conducted some controlled tests, and compared the M6 TTL’s meter with both incident and reflected readings from a Sekonic L-358 — and found the M6 TTL to be accurate and, thus, 100% usable.

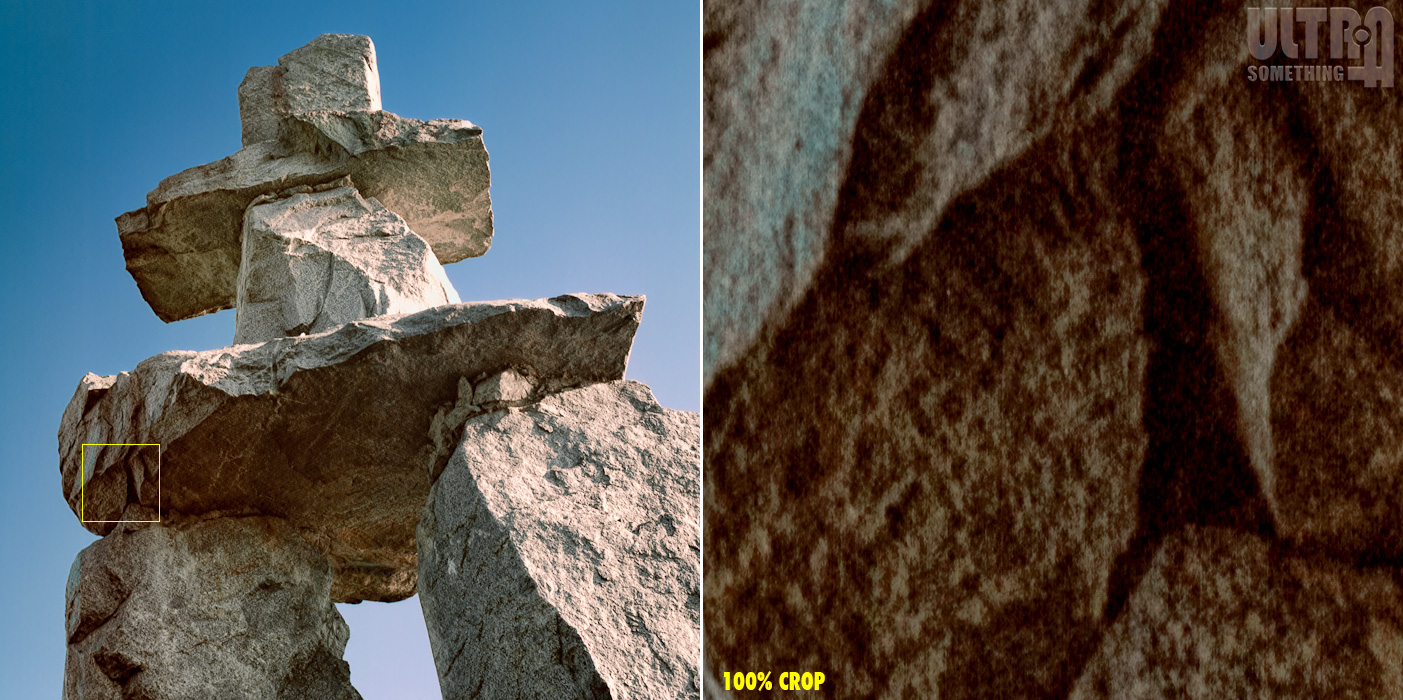

Tri-X film rocks. OK, this has absolutely nothing to do with the Leica M6 TTL, but it has everything to do with the reason I now own this camera. Black & white negative film is far more forgiving of exposure errors than digital sensors, color positive film, or even color negative film. Its logarithmic response to light is a more accurate reflection of how human’s perceive it than the linear response of digital sensors, and it’s this logarithmic response that allows black and white negative film to capture more detail in both the highlights and shadows than digital cameras. Having a camera as fine as a Leica M6 TTL is pointless if it doesn’t offer some kind of advantage over modern cameras — and Tri-X film is, for me, a definite advantage.

Every product I’ve ever used, no matter how exemplary, has featured a few annoyances. In the case of the Leica M6 TTL, there are two things that irritate me:

Focus patch flare. This is a well documented M6 complaint, and its origins extend all the way back to the M4-2 in the late 1970’s. But until I got the M6 TTL, those complaints were just words on a page. Now these words have meaning. Flare is definitely a problem with the M6 TTL.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with rangefinders, I’ll provide a bit of background: When you look through a Leica’s viewfinder, you see some framelines and a center patch overlaying the scene you wish to photograph. A fresnel covered window on the camera’s front gathers ambient light that illuminates both the framelines and the center patch to insure they remain visible in even the dimmest lighting conditions. The center patch is particularly important, since you use this area to focus your camera. The patch displays a split image — two views of the same scene, side-by-side. By rotating the focus ring on your lens, you bring these two images into alignment. When aligned, the object shown within the patch is in focus. The problem, to put it succinctly, is that these illuminated areas within the M6 sometimes appear over-illuminated — to the point of becoming opaque white light. When the center focus patch in your M6 viewfinder turns all white, you can’t see to focus the camera. Needless to say, this kinda sucks.

The situation occurs only when light hits the fresnel illumination window at certain angles. Unfortunately, I apparently have an uncanny knack of photographing subjects when the ambient light just happens to correspond to one of these problem angles. I found I could work-around the flare by tilting the camera a bit, focussing, then re-orienting the camera correctly. Ultimately, there was too much “work” in this work-around. So I applied a different solution — Post-It Notes™. Specifically, I cut out a little section of Post-It Note, and stuck it over the fresnel illumination window to cut down on the amount of light being transmitted to the focus patch. The solution works extremely well — I rarely experience lens flare and, in almost all cases, the window still gathers enough light to adequately illuminate the framelines and focus patch. I must admit, I find it somewhat disturbing that a precision piece of legendary machinery requires the application of a Post-It Note to perform properly. Fortunately, I recently discovered that Leciagoodies makes an aftermarket window covering that performs a similar function to my Post-It Note — a sort of polarized plastic that you stick over the illumination window, which reduces the amount of oblique light entering it. I’m still awaiting the arrival of this product so, for the time being, my M6 remains permanently adorned with a yellow Post-It Note.

The situation occurs only when light hits the fresnel illumination window at certain angles. Unfortunately, I apparently have an uncanny knack of photographing subjects when the ambient light just happens to correspond to one of these problem angles. I found I could work-around the flare by tilting the camera a bit, focussing, then re-orienting the camera correctly. Ultimately, there was too much “work” in this work-around. So I applied a different solution — Post-It Notes™. Specifically, I cut out a little section of Post-It Note, and stuck it over the fresnel illumination window to cut down on the amount of light being transmitted to the focus patch. The solution works extremely well — I rarely experience lens flare and, in almost all cases, the window still gathers enough light to adequately illuminate the framelines and focus patch. I must admit, I find it somewhat disturbing that a precision piece of legendary machinery requires the application of a Post-It Note to perform properly. Fortunately, I recently discovered that Leciagoodies makes an aftermarket window covering that performs a similar function to my Post-It Note — a sort of polarized plastic that you stick over the illumination window, which reduces the amount of oblique light entering it. I’m still awaiting the arrival of this product so, for the time being, my M6 remains permanently adorned with a yellow Post-It Note.

Battery Life. I suspect the average gnat enjoys a lifespan longer than that of an M6 TTL meter battery. When I first purchased the camera, its light meter batteries were dead. I shot about a half roll of film before finally purchasing a pair of 1.5V Silver Oxide button cells to power it. I then finished that roll, and a second 36 exposure roll after that. Halfway into the third roll, the meter batteries died. Huh? How could these batteries die after only 2 rolls of film? Yes, I had personalized another of the more common M6 complaints — battery life.

Leica claims the batteries should allow for 8 hours of meter use. The camera activates the meter for about 10 seconds every time you press the shutter release. That means, theoretically, you should be able to push about 80 rolls of 36-exposure film through the camera before replacing the batteries. Obviously, in real-world usage, you’ll sometimes half-press the shutter release just to take a meter reading. Assuming you do this before every exposure, you’ll halve the life of the battery to 40 rolls of film. So why did I get only 2 rolls? I suspect the answer is two-fold. First, I used a pair of 1.5V Silver Oxide cells rather than a single, fat 3V Lithium Cell. Second, it’s quite easy to half-press the shutter release accidentally — either when you’re carrying the camera or, more likely, when it’s bouncing around in a camera bag. Back when I first fit my M8 with a soft-release, I had a similar problem — it was so easy to trigger the shutter that, when I put the camera in my bag and went for a walk, I’d pull it out and discover I’d taken 100 new photos of the inside of my bag. This forced me to learn a new trick with my digital Leicas — to turn them off every time I put them in a bag. In the case of the M6, I’m not using a soft release, but I suspect the shutter release is getting a fair amount of half-presses inside my camera bag. Ideally, I would just “turn off” the camera like I do with a digital M. But with the M6, it’s not so easy. Since the M6 is a mechanical camera, there’s really no such thing as an on/off switch. That said, Leica did provide a spot on the shutter speed dial that turns off the meter. Unfortunately, it’s quite time consuming to actually rotate this dial to the OFF position every time I put the camera away, and it’s not something that’s become part of my muscle memory. I’ve now installed a Lithium cell into the M6 and I sometimes remember to turn the shutter speed to “off” when I put the camera in my bag, so I’ll be monitoring real-world battery life under these new conditions. I suspect frequent battery depletion will be an ongoing issue with the M6, which will effectively convert it into an M4-P — a fine camera in its own right, but I bought an M6.

Some of the Leica M6’s features qualify as neither “good” nor “bad” — just “curious.” Here, then, are a few curiosities you might want to learn about before ordering your own M6 TTL:

The tipsy tripod socket location. Because Leica wanted these cameras to be as small as possible, the tripod mounting socket is located under the film advance spool. Locating it in the middle of the body, centered below the lens, would have necessitated a taller body, which is contrary to Leica philosophy. Fortunately, Leica users are notorious for rigidly forgoing tripods and, truth be told, I’m far more likely to need one with my SLR than with a rangefinder. Still, I always carry a little 6″ flexible tabletop tripod with my digital M’s — just in case I need to use a particularly long shutter speed. But the crazy positioning of the tripod socket on the M6 makes this particular tripod useless — the camera simply tips over, and rolls around the table laughing at the ridiculous little tripod.

The meter’s battery replacement is much more fiddly than it need be. You would never want to risk replacing the battery in the field because you’re guaranteed to drop both the battery, and the little round screw-out battery holder. If you drop them at home, no big deal. But if you’re on the streets and you drop them down a sewer, you’re hosed. With a different design, the battery compartment could easily have become a quick way to “turn off” the meter whenever you didn’t actually need it. But, as it is now, you would actually have to unscrew the holder, fiddle with removing the battery, put it in a pocket, then screw the little holder back into the camera — a process guaranteed to make certain you won’t ever bother to remove the battery, even if you won’t be needing it for the day.

The shutter speed dial selects only whole-stop values — I was expecting half-stop settings, like the digital Leicas. It’s not that Leica hid this fact — not at all. It’s just that I never even thought to check. It is possible to set the shutter dial between detents and, in fact, the camera will oblige with a shutter speed that’s somewhere between the two stops — unfortunately, this does not yield any sort of repeatable shutter speed, nor are you likely to know the value of the interim speed. Fortunately, you still have half-stop resolution via the aperture settings on the lenses, but it did take me a couple weeks to get comfortable with the loss of the interim shutter speeds. That said, I no longer miss them at all.

It’s All Relevant

I’ve met many people who claim to be passionate photographers, yet they turn up their nose at the idea of shooting film… or even rangefinders, for that matter. I wonder how someone can claim to be passionate, yet simultaneously dismissive of options and alternatives? In the 170 years since Louis Daguerre invented the daguerreotype, mankind has produced an impressive number of photographic processes, methods, and equipment options. All are at our disposal. Does the world really need another SLR-toting HDR specialist? If your passion is photography, then isn’t your passion to create, not to limit?

There’s never been a better time to buy quality film cameras at crazy low prices. No matter what you’re shooting now (and, for the majority of ‘passionate’ photographers, that means either Nikon or Canon), you can buy professional or prosumer film bodies that mount all your existing lenses. What’s more, if you’re currently shooting a cropped sensor, shooting film will give you a ‘full frame’ experience without having to shell out big bucks for a full frame digital.

Yes, film requires additional steps. It requires processing — a new skill should you wish to do it yourself, or an added expense if you wish to send it to a lab. It requires scanning — also a new skill should you wish to do it yourself, or an added expense if you wish to send it to a lab. And, with film, you can throw away that last decade you spent worrying about resolution — that’s digital’s forte. Film is all about tonality.

My photographic world now revolves around rangefinders, and my system of choice is the Leica. With the M6, I heeded my own advice, and bought a film camera to both back up and extend my M-series capabilities. I am absolutely better off for doing so, and the M6 will remain mine for life… unless some doofus unwittingly dumps an MP on the market at a ridiculously low price.

©2010 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS: “Fine Arts” and “The Wall ‘Twixt Fantasy and Fact” were shot with a Leica M6 TTL, using Tri-X film rated at ISO 1250 and developed in Diafine. “Habitable Art”, “Business Casual,” and the drug bust sequence were shot with a Leica M6 TTL, using Tri-X film rated at ISO 400 and developed in Ilfotec DD-X. The color shots of the Leica M6 TTL were shot with a Canon 5DmkII.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.