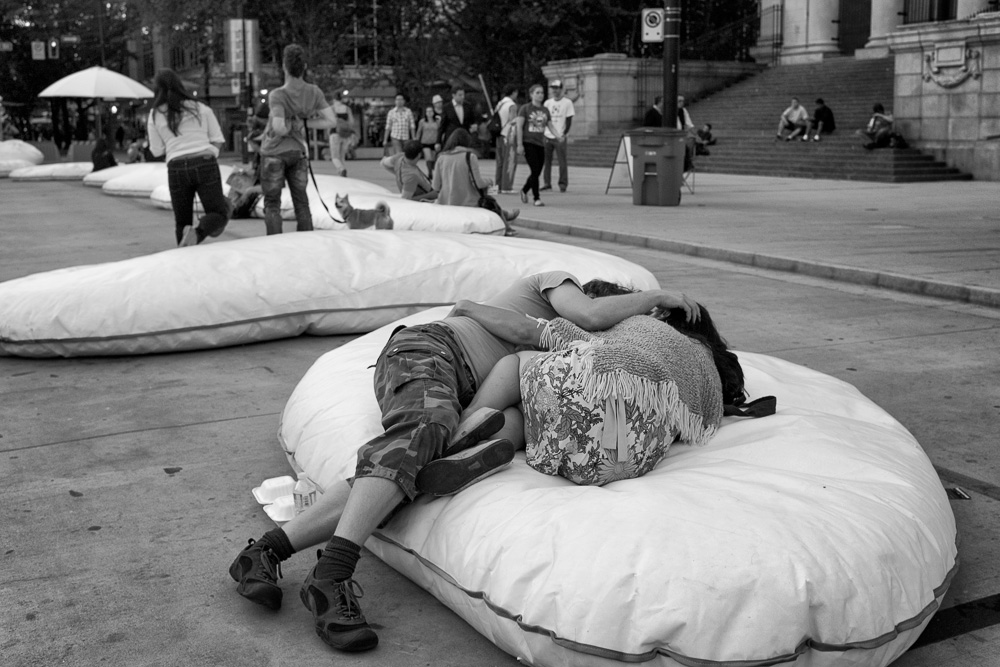

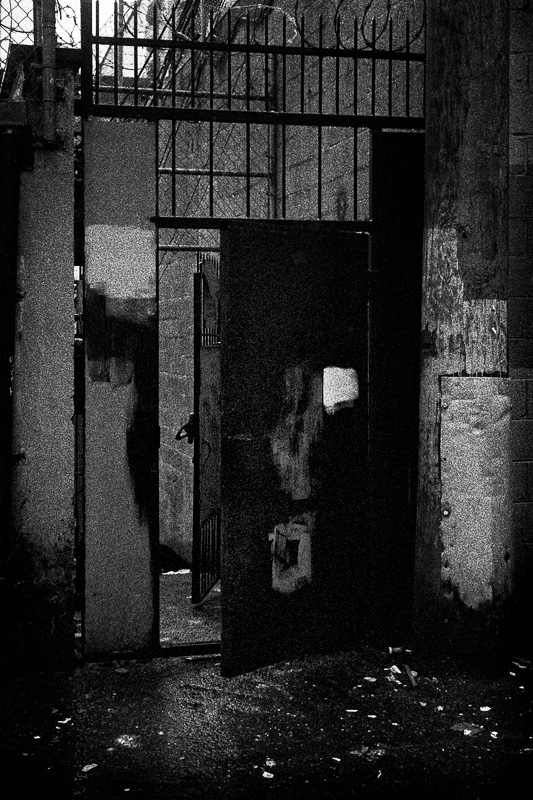

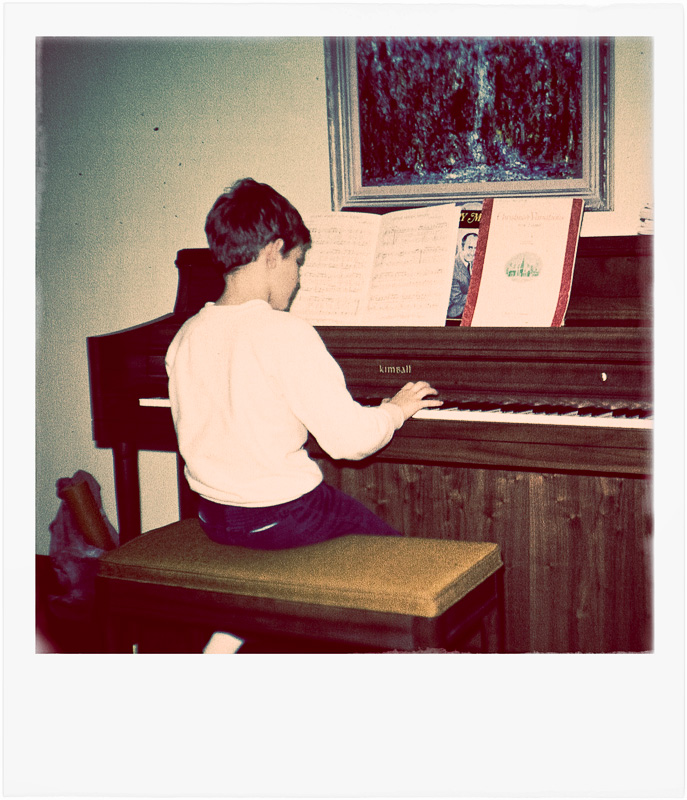

mas•quer•ade (noun): A false show or pretense.

Masquerade from grEGORy simpson on Vimeo.

©2013 grEGORy simpson

ABOUT THESE PHOTOS:

There are 74 of them in this vBook — shot with all manner of cameras, lenses, film and sensors, and processed with all sorts of chemicals and software. They were sequenced in Final Cut Pro X and set to a custom score, which was recorded into Ableton Live using all 10 of my fingers and at least that many software-based synthesizers. Anyone intrigued enough to learn the meaning of the vBook’s final frame should mosey on over to another ULTRAsomething article — the one with the coincidentally apropos title of Reject Intent.

If you find these photos enjoyable or the articles beneficial, please consider making a DONATION to this site’s continuing evolution. As you’ve likely realized, ULTRAsomething is not an aggregator site — serious time and effort go into developing the original content contained within these virtual walls.

.jpg)

.jpg)